Pokémon Sword and Shield is the 8th generation of the Pokémon series and the first core entry on Nintendo’s console-handheld hybrid, the Switch. The prospect causes my imagination to whirl: The winding worlds of Pokémon’s portable installments on a platform comparable to a home console’s power with the scope and ambition of a AAA studio RPG. I am sorry to say that Sword and Shield is none of these things, feeling at its best like a handheld videogame with HD graphics. Maybe that’s not it’s fault. Maybe I shouldn’t expect it to become more epic and open and less like what Pokémon has always been. Yet even by the standards of its own series, Sword and Shield feels short, small, and unambitious.

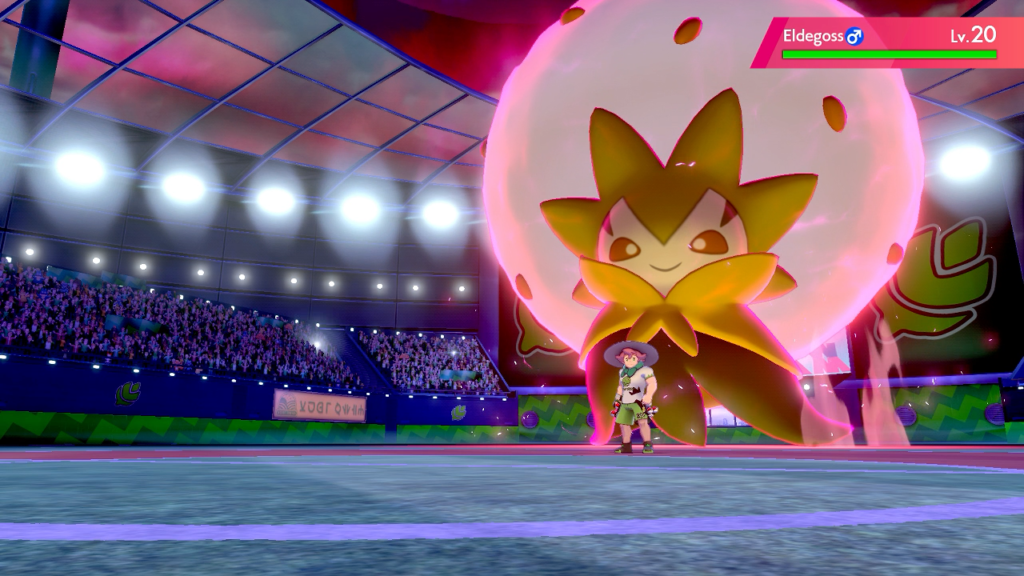

In the world of Pokémon, young men and women leave home to find and capture Pokémon, wild animals with fantastic powers, and pit them against other trainers in friendly competition. Pokémon battling is the most popular and important activity in this world: Cities are built to serve it, economies are based on it, cultures are built around it. Sword and Shield’s Galar region is no exception. Since Galar is based on our world’s United Kingdom, Galarian Pokémon battling is imagined through the lens of football fandom: Gym challenges take place in stadiums before passionate crowds cheering their local squad; trainers compete in a jersey emblazoned with their league number; Marnie, one of the rival trainers, is supported by rowdy trouble-making hooligans; the League Champion is determined through a playoff system rather than the familiar Elite Four. This interpretation of the Pokémon League makes me feel more part of a competitive culture than any other Pokémon title.

Despite these Briticisms, Sword and Shield is still rote. I can play mad libs with its scenario design: I create my trainer player character and meet my neighbor/rival. I also meet the region’s Pokémon Professor who tasks me with cataloging all the region’s Pokémon in a Pokédex. I travel through the numbered routes connecting each town—what a coincidence that the player character’s hometown always seems to be on Route 1!—visiting themed gyms to defeat their leaders, earn all eight gym badges, and challenge the region’s reigning Champion in sanctioned combat. Along the way my trainer dismantles a villainous group’s schemes because they’re blocking the path to the next gym and somehow their world-ending plot feels incidental to becoming the very best. Sun and Moon, the Pokémon Generation 7 entry, finally abandoned gyms and made overtures towards a more ambitious plot and characterization, so it’s disappointing to see Sword and Shield take a big step backwards to the same scenario design Pokémon has been employing since Kanto.

Sword and Shield’s combat AI is also unchanged. As always, computer-controlled trainers retain their curious obsession with exactly one Pokémon type so steamrolling any particular area requires a single Pokémon that counters them. It’s not until Champion Leon, the literal final fight, that an opponent puts up any recognizable resistance with a team built to overcome typing disadvantages.

Opposing trainers are further hindered by the same rudimentary AI they’ve always had. It’s been twenty-four years and they still don’t know how to put abilities like Protect and Detect to practical effect, turning any battle with a trainer who uses them into another wasted turn before my inevitable victory. The same goes for opposing trainers who use items; not once does that Max Potion or Full Restore help them survive for more than another turn or two in which they continue to do nothing whatsoever. It’s long past time for Pokémon’s AI combat to feel like competitive play and not tedious autowin battles that only slow my progress to the endgame.

Speaking of wasting my time, Sword and Shield’s new combat gimmick is Dynamaxing. Galar’s gym-stadiums are built on founts of power that allow Pokémon to grow to gargantuan proportions for several turns. This growth comes with a corresponding increase in power but each move is reduced to a single powerful attack of matching type. All AI opponents will Dynamax their final Pokémon. Every single one. There is no surprise or strategy involved in when it will happen. They Dynamax their last Pokémon, so I Dynamax mine. My Dynamaxed Pokémon knocks out theirs before it can make a move. It’s predictable. It’s boring. It’s pointless. It’s time for Pokémon’s AI to learn how to play Pokémon and for one-generation gimmicks like Dynamaxing to go away.

Battling Pokémon’s AI trainers has never been challenging or interesting, but past titles have made up for that with large worlds full of criss-crossing paths, backdoors to earlier areas, items hidden in obscure nooks and behind special barriers, and caves, forests, and office buildings serving as makeshift dungeons to explore and overcome.

Sword and Shield has none of these redeeming features. Galar consists of a mere ten Routes; the next-smallest region is Sun and Moon’s Alola with seventeen Routes; Kanto, the first Pokémon setting on the 8-bit Game Boy, has twenty-five. Past a few token fields of grass populated by wild Pokémon, these Routes have little to explore and few Trainers to battle. The tiny side areas on each route seem to groan “we know we’re expected to be here but this Route only exists to put more footwork between each town.” I counted how many side paths I couldn’t travel down until I got the water-traversing bicycle obtained near the end of my trainer’s quest. There are three.

Galar doesn’t make up for its small size with more and dense dungeons. It has five, and I won’t bother comparing that to previous Pokémon videogames because suffice to say it’s less. And I’m being generous by calling some of these “dungeons” as their design is a straight line with one or two token sidepaths, also straight lines. Sword and Shield is on the most powerful hardware a Pokémon videogame has ever been on and has the smallest and simplest world in the entire series.

“But what about the Wild Area?” I hear you saying. The Wild Area is a glimpse at what I hoped Sword and Shield would be, but only a glimpse. Taking up the center of the Galar region, it is a plain packed with wild Pokémon where I am cut loose to explore a non-linear area with a rotatable 3D camera. This is something I’ve dreamt about since Pokémon Stadium on the Nintendo 64, but this ability is restricted to this one area where I spend a fraction of my total playtime. The rest of Sword and Shield is locked to the same perspective as Pokémon’s 3DS entries.

The Wild Area is featureless. Yes, there are some hills, rivers, and lakes, and the northern panhandle deteriorates into a sandy prairie, but these differences are cosmetic. There are no mountain peaks to climb revealing the scale and majesty of the Wild Area below me (there is no scale or majesty, the entire Wild Area may be crossed in a few minutes). There are no caves to spelunk, discovering secluded fishing holes beside primordial lakes. There are no fog-choked forests haunted by Gastlys, Phantumps, and mischievous Galarian Ponytas. There are no crumbling ruins filled with ancient traps and forgotten horrors. The Wild Area is a L-shaped grass expanse that changes from green to brown.

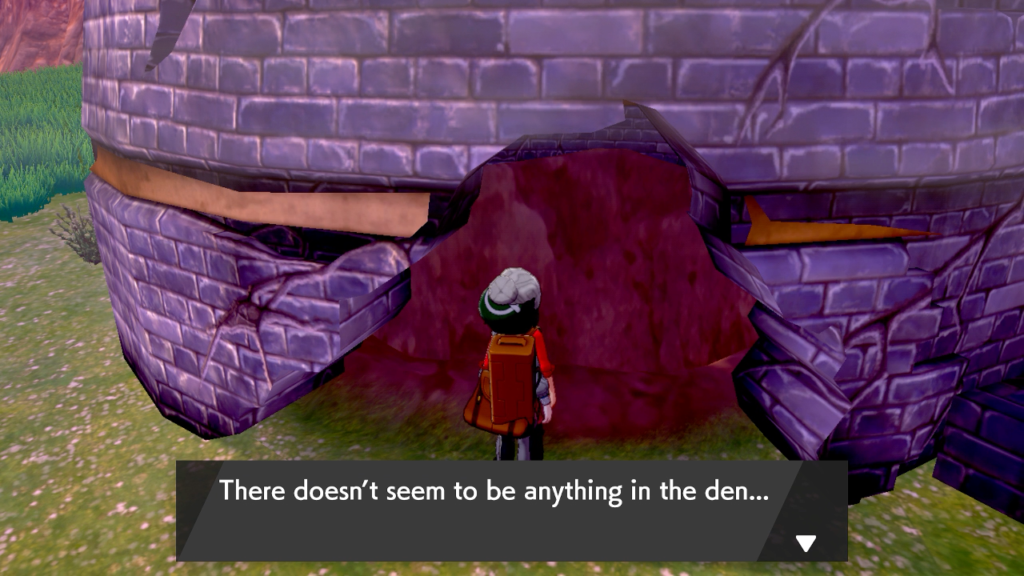

There is a little more to the Wild Area than grass and wild Pokémon. It also contains glowing dens that host Max Raid battles, 4v1 duels against massive Pokémon berserkers I can tackle with other players online. When I’m connected to the internet I can see other player characters, but they either stand motionless or run in straight lines before fading into the ether; they are phantom facsimiles pantomiming something another player might be doing, not avatars representing another player’s actual actions. There’s no set path through the Wild Area, but there’s nothing to discover either. There is no game-changing secret hidden behind the next hill or around the next corner, just another pocket containing another patch of grass or Max Raid den. From the moment I set foot in the Wild Area I’ve already seen everything it has to offer.

My trainer visits the Wild Area twice during their journey and both times it is to reach the next set of Routes. There is never anything to do there during the main scenario; much like the Routes, its primary purpose is to have more space to walk across so the small world feels somewhat less small. It’s the best area in the series for catching new Pokémon and the Max Raid battles provide a welcome dose of online cooperative play, but there’s little reason to be there until the post-game. It feels extrinsic. It’s the Safari Zone with limited online features. It’s a laughably unimpressive tech demo. It’s an afterthought.

Sword and Shield doesn’t only play like a last-gen handheld RPG, it sounds like one too. I was disconcerted from the first cutscene where Chairman Rose, head of the local Pokémon corporation and League manager, addresses a packed stadium. His mouth moves and subtitles transcribe what he says but there’s no voice to accompany it. Sword and Shield is a AAA RPG in 2019 with no voice acting in its many cutscenes. I think unvoiced dialog through prompt-driven text blocks is a valid aesthetic choice, but not during subtitled cinematic cutscenes.

If you’ve never plugged a handheld platform into a sound system to listen to the music and sound effects, it’s something you must enjoy at least once. The low sound quality necessitated by limited storage space is easier to ignore on cheap hardware, but it has its own charm coming from a set of speakers meant for higher quality media. Or you can play Sword and Shield in docked mode and get a similar experience, except the vibrant HD graphics clash with last generation’s handheld audio design. Even with the massive storage space available to the Switch, Pokémon still “roar” with garbled electronic static. The music is synthesized, and not in an artfully retro way. It sounds hollow and tinny.

If I were to listen to this soundscape through a veil of ignorance, I would conclude I was listening to a 3DS videogame. For all the noise that a small group of loud idiots made about Sword and Shield’s alleged visual shortcomings, it is in sound design and music production that it feels like things were done on the cheap.

I hoped Sword and Shield would be transformative. Instead it’s the same videogame Pokémon has always been. More disappointing still it’s not even a good example of that familiar videogame, lacking the strengths that have offset the series’ typical weaknesses. The kindest thing I can say is it’s safe. It doesn’t try to alter what Pokémon has always been, but after dwelling in the handheld space for so long that’s exactly what Pokémon’s main series debut on a big-screen platform should have done. A jump in hardware sophistication from the 3DS to the Switch should have seen a commensurate jump in design and ambition for this flagship RPG series. Instead it’s a 3DS videogame with HD graphics. That’s a shame. It could be so much more.