When I was a child, Saturday evenings were often time for my parents and I to visit our friends, a similarly-aged and -privileged family living across town. While our parents whiled the evening with movies, my friend and I sequestered ourselves in his tiny bedroom. With controller cables stretching from the NES to the upper level of a bunk bed, we would join Mario and Luigi on their quest to save Princess Toadstool once again from the clutches of the villainous turtle-king Koopa in Super Mario Bros. 3. We rarely made it past the first few levels, with its treacherous pits and roving bands of Hammer Bros, but we were always ready to try again, imprinting into our memories the lush hills and blue caverns of Grass Land.

These memories haunt every moment I spend with Super Mario Bros. 3. Even though I now play lounging on my IKEA couch, I can still feel the pinch of the bunk bed’s wooden frame on my dangling legs when I slide down the icy slope at beginning World 1-5, crashing through the Buzzy Beetles that dare get in my way. It was as I hurtled down that slope in my most recent playthrough and regarded it as a functional novelty that it dawned on me how much my relationship with this prototypical videogame has changed in my lifetime. To a six year old, hopped up on Pepsi and reveling in the naughty thrill of playing videogames at 1am, that slope was a rocket chute.

Thanks to The Wizard, a 1989 feature-length advertisement for Nintendo products disguised as a coming-of-age road trip movie, most kids knew about the hidden Warp Whistles. As a child with the expected coordination and attention span, these Whistles were revelatory, backdoors to the latter stages I might never see if I were required to play from World 1 on every attempt.

But when I used the Warp Whistles to skip straight to Dark Land, I missed Super Mario Bros. 3’s best levels: A tower that connects Sky Land’s terrestrial first half to its empyrean second; Desert Land’s quicksand pit with its road-blocking twister and infamous Angry Sun; or the towering mazes of Pipe Land where walking off the right side of the screen causes Mario to reappear on the left. Time and technology have been kind to this videogame, so now I may ignore the Warp Whistles knowing that battery-backed memory and save states ensure I can pick up where I left off if I am unable to save Toadstool in a single sitting.

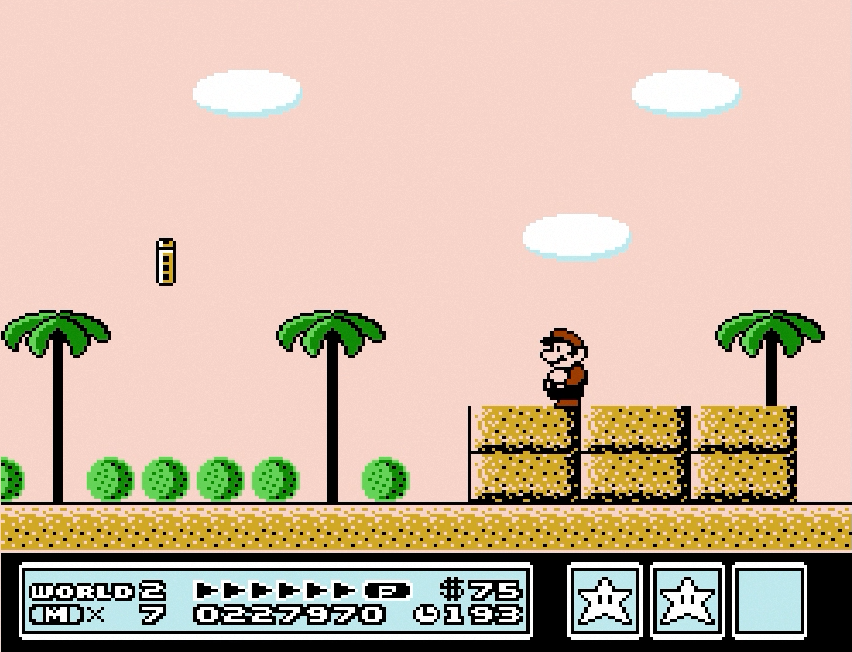

The Warp Whistles also made us miss Super Mario Bros. 3’s inspired overworld design. Where the previous Mario videogame forces me to trudge forward, level by level, this adventure gives me a modicum of choice. I begin on each world’s map, mountains and trees bobbing in time with the music, and move along straight paths to the level I want to play next.

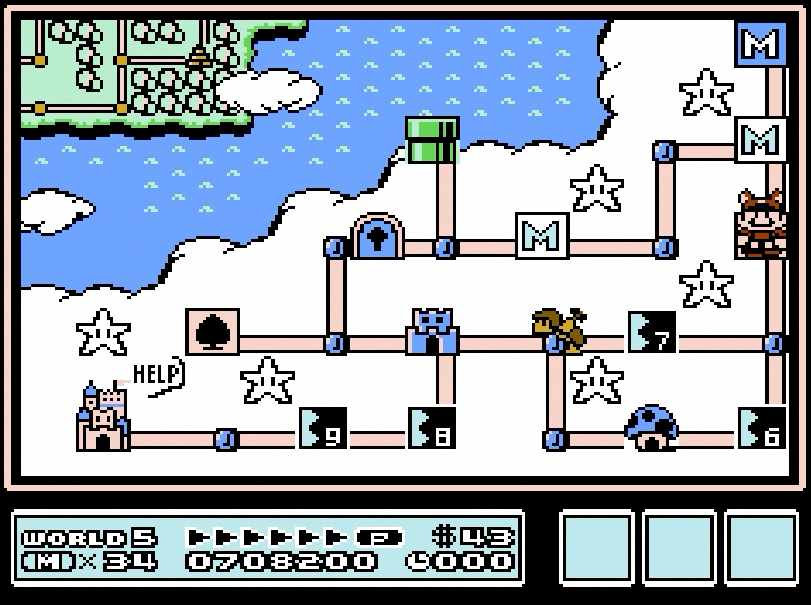

The first world, Grass Land, does not offer many choices in level order, but later worlds offer more agency to tackle levels in the order I wish. Or I may choose not to play them at all, sneaking past the greatest challenges using circuitous routes, warp pipe shortcuts, and strategic use of the precious Hammer item to smash roadway-blocking boulders. Other roads are blocked by doors which unlock when I beat Boom Boom in a nearby Fortress; these doors remain open even after a Game Over, ensuring a more direct route to each World’s final Airship challenge should the later challenges prove too much and I am forced to start that World over from the beginning.

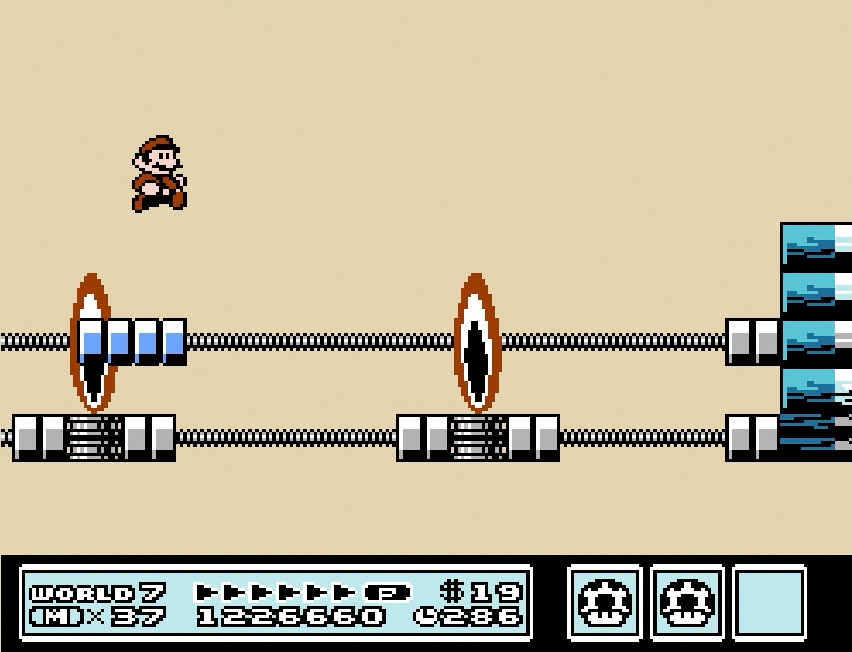

The Airships are Super Mario Bros. 3’s most enduring legacy, serving as the Bowser clan’s vehicle of choice in more recent titles and returning as a tileset in both the Super Mario Maker videogames. Mighty flying fortresses that careen through the sky as Mario assaults them, airships are defended by batteries spewing Bullet Bills and cannonballs, often have more pits than solid ground, and culminate in an ultimate showdown with one of the villainous Koopa Kids. It was these levels that sent me grasping for the nearest Warp Whistle.

Failure in an Airship level would send it fleeing along the network of roads in the world map, forcing me to give chase. The more levels I cleared in the world, the fewer places the airship would have to hide. But if I focused more on moving to the palace than exploring the map I might be forced to play a level I avoided to reach the airship and try again. It’s a beautiful confluence of videogame mechanics: I may choose to bypass some levels; the airship moves when I fail an attempt; consequently, I may find the first mechanic affecting what happens if the second mechanic occurs.

If it wasn’t an Airship that stopped me cold, then it was one of Super Mario Bros. 3’s cunning puzzle levels. Inspiring some of the best community creations in Super Mario Maker, these levels disrupt the lightning-paced obstacle courses with doorway labyrinths and shell-tossing tests. If you’ve ever played a Mario Maker level and been dropped from a doorway into a Blooper-infested water trap or used a Koopa shell to clear a narrow passage to the exit, those ideas are seeded here, and future mainline Mario titles have shied away from this level of deviousness. As part of the entire collection of levels they are the exception, not the rule, and often prove frustrating roadblocks impeding a sense of forward momentum, but that only makes these rare puzzle levels all the more memorable.

A lot has changed since I first started committing the hills and caves of Grass Land to memory thirty years ago, sitting on that bunk bed, prising magic Warp Whistles from behind scenery to ensure I could assault Dark Land and face off with King Koopa. Braving the treacherous Water Land and the sprawling Ice Land seemed a fantasy, but now I clear the entire videogame with the bare minimum of frustrated grumbling. There are few others with which I have a longer and more evolving relationship, and I am grateful for it to be one of my formative experiences.