Despite its name, Final Fantasy Adventure is not a Final Fantasy videogame. It is the first installment in Square’s action-RPG Mana series, originally released for the Game Boy in 1991. It is set in a fantasy world that has been almost totally conquered by the Glaive Empire led by the tyrannical Dark Lord. The last step in his plan for world domination is to reach the Mana Tree, the source of all life, atop the unscalable Mount Illusia and absorb its power. The player character is a man named Sumo, a warrior enslaved in gladiatorial contests by Dark Lord. One day, Sumo’s fellow gladiator Willy is mortally wounded and presses Sumo with his last request: Escape and warn the Gemma Knights, the protectors of the Mana Tree, of Dark Lord’s plan. Killing the monster that guards the slave’s cells, Sumo escapes and sets out on an adventure to save the Mana Tree and bring down the Glaive Empire.

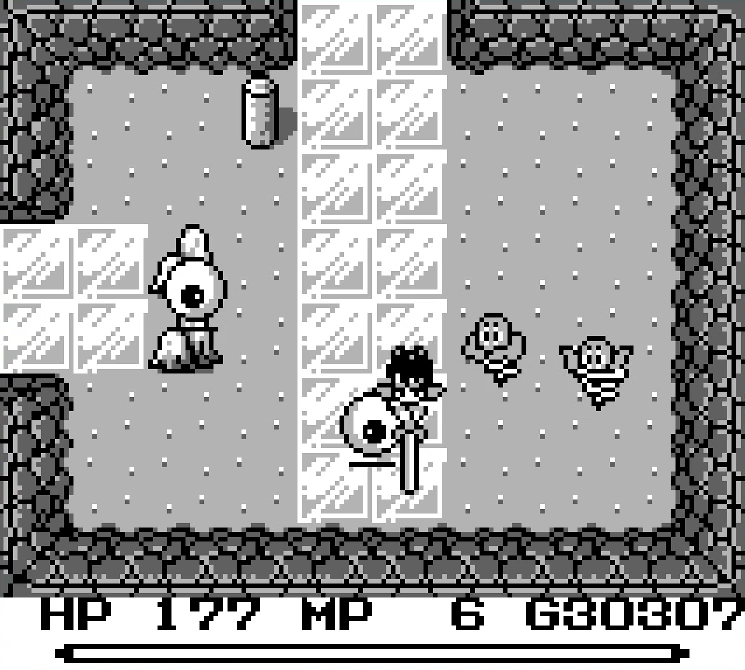

Final Fantasy Adventure seems unremarkable now but was novel upon its 1991 release for combining stat-driven RPG combat with real-time hack-and-slash game design. We recognize this now as an “action-RPG.” I can equip Sumo with different weapons that have varying ranges like swords, axes, and whips. He can also learn magic, from basic curative magic to damaging elemental spells.

Sumo earns experience points when I kill enemies that increase his overall experience level at accumulative milestones. Upon a level up I can choose to improve one of his four stats: Stamina, which increases his total hit points; Wisdom, which increases his total mana points; Power, which increases the damage he deals with weapons; and Will, which increases the speed his Will Meter fills.

The Will Meter is what makes Final Fantasy Adventure stand out from other action-RPGs and even other Mana series entries. The meter fills constantly but resets whenever I attack. If I wait to attack until the meter is full, the effect of Sumo’s equipped weapon is changed. Axes and polearms magically reappear in Sumo’s hands after being thrown to the other side of the screen. Whips and sickles gain even more incredible reach beyond their base range. Swords gain the most bonuses, suggesting they are Sumo’s specialty. If I attack while moving forward with a sword, he will fly back and forth across the screen, striking everything in his path; if I hold the attack button while standing still, he will spin his sword in circles for several seconds. The Will Meter fills so slowly at the start that it is practically useless, but by the endgame it fills fast enough to be a valuable tool against Sumo’s most powerful enemies.

Sumo’s combat mechanics are simple but have enough depth to be interesting. The same cannot be said for enemies, who don’t attack with anything resembling purpose or cunning. Instead they wander around the screen and deal collision damage to Sumo if I cannot move him out of their way in time. Some areas try to make enemies more threatening by filling a screen with obstacles but this does little to increase the danger they pose. After Sumo gains a few levels most enemies die in a single hit, particularly if I invest all of his level ups into Power. At least, this is the case with enemies who are not immune to certain weapons. Final Fantasy Adventure is at its most tedious in its final hours when I am shuffling through my stocked weapons, searching for an effective one, because the current batch of enemies are immune to my equipped weapon. Protip: Never sell your Silver Sword.

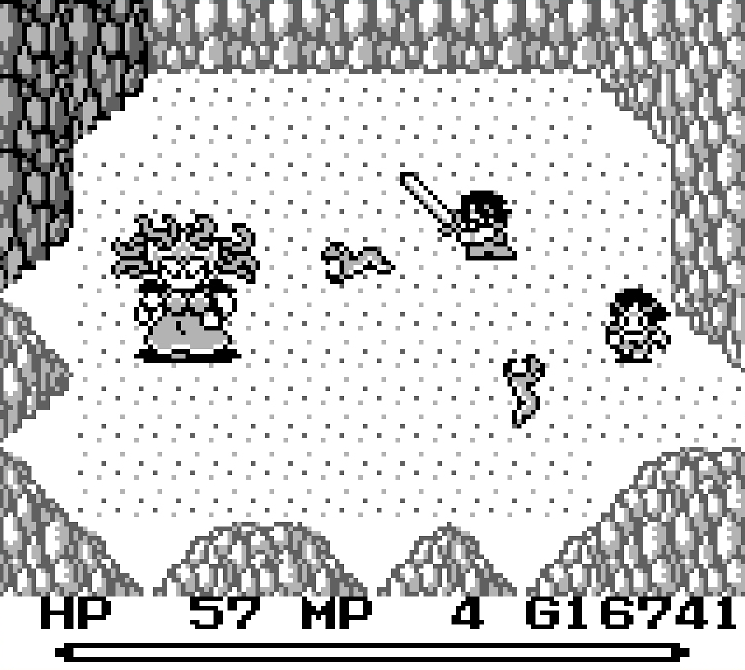

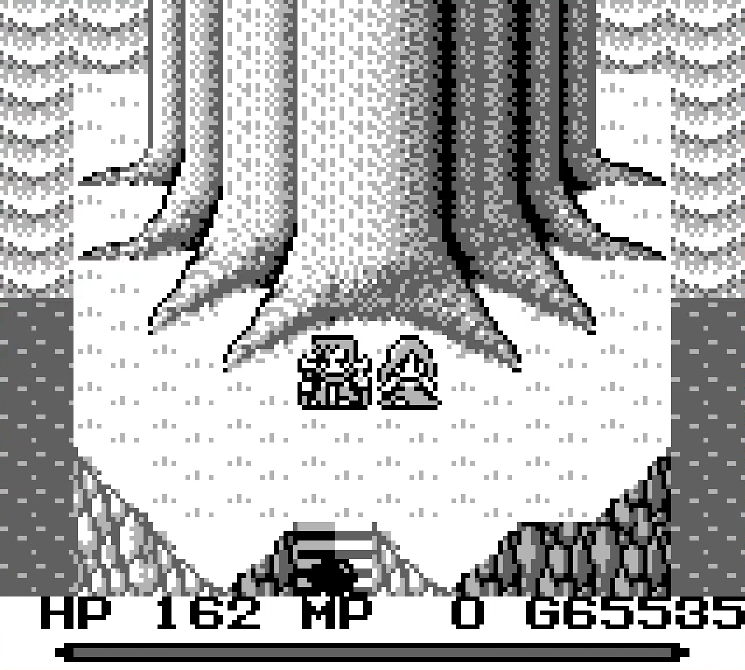

Bosses require a little more effort. Running the gamut from dragons to giant metal crabs to krakens, they move in predictable patterns but are so massive that collision damage can be difficult to avoid even if I know how they’re about to move, particularly in cramped battlefields. Hit-and-run tactics work well early on, but later I must take advantage of the Will Meter’s weapon abilities to stand a chance as bosses become ever-larger while their hit boxes become paradoxically smaller.

Final Fantasy Adventure, despite its crudity, manages to get its RPG monsters right: Standard monsters are cannon fodder and the bosses that rule them are powerful brutes. The former requires dogged persistence and the latter careful strategy to overcome.

Sumo is joined at various points on his adventure by other world denizens who have their own goals which happen to align with the protagonist’s. They’re about as effective in combat as standard enemies, wandering around the screen and attacking at random. This does not mean they are not useful. They cannot die, and some provide invaluable bonus abilities. I can access these abilities by opening the menu and selecting the “Ask” option. Fuji, a young woman I rescue from a monster attack early in the story, provides free Cure magic. Amanda, another escaped slave from the Glaive Empire, can heal the Stone debuff, and she accompanies Sumo in a dungeon that happens to be full of enemies that cause the Stone debuff. Marcie the Cyborg restores Sumo’s mana points, for free, as much as I ask her to. Not every companion has an ability, but those who do take the already-slight difficulty and break it completely.

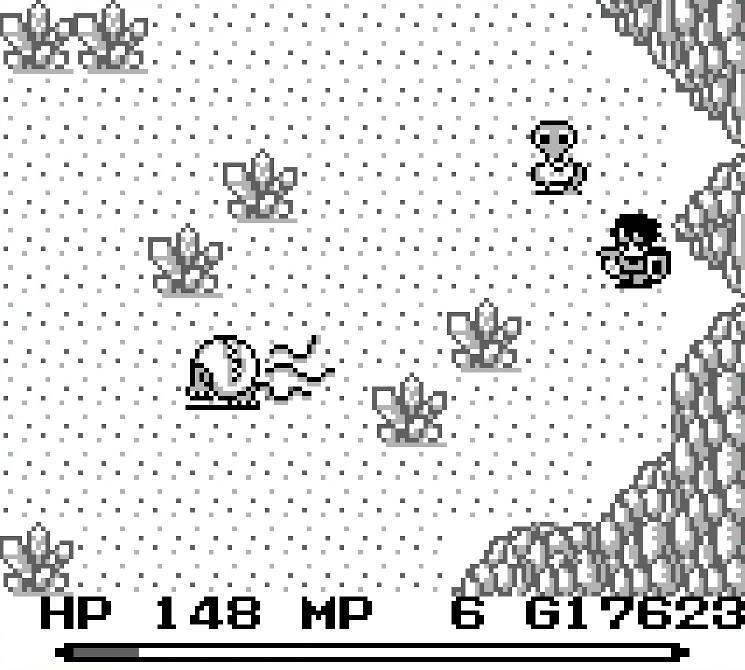

Sumo’s quest for the Mana Tree takes him across the world. Despite the Game Boy’s monochromatic color palette and limited storage capacity, Final Fantasy Adventure’s graphic designers admirably create a sense of place through smart use of its art assets. There are three different deserts in the world but I’m never confused about which one I might be in because each is constructed differently and contains unique attributes; the Jadd Desert has suffocating rock cliffs sheltering several oases, the Crystal Desert is (naturally) marked by crystal formations, while the Palmy Desert is a narrow peninsula notable for its many palm trees. The rest of the world has more diverse biomes and at a glance I can tell my location by looking at the object nearest to Sumo.

What is not always clear is what I am expected to do next. A good example happens early in the story. I guide Sumo and Fuji into a marsh and discover a tower where they are allowed to sleep by the tower’s caretaker. Fuji is abducted during the night and the caretaker will not allow Sumo to investigate the tower’s upper floors. By speaking to the other guests staying at the tower, I learn of a cave where the tower’s master disposed of a mirror. But the cave has a door, and the door is locked. Another guest mentions the Lizardmen’s Nest, where I find the key to the cave door. I get the key, raid the cave, find the mirror, which reveals the tower’s caretaker is a zombie. Killing the zombie caretaker allows me access to the rest of the tower, where I rescue Fuji from the clutches of a vampire.

There’s nothing that suggests these locations are related. It’s typical of the design ethos of Final Fantasy Adventure’s day where I am meant to infer a location’s importance by proximity more than context and pursue the vague hints of random non-player characters even when there are more pressing things happening in the plot. This is just one example; I have read reports of the puzzle that opens the Cave of Medusa keeping players stumped for years.

When not exploring the forests, deserts, and mountains of the world, Sumo’s quest takes him into its dungeons. These locations are less distinct than the overworld, but since they only exist to be visited once it’s not a problem. Each dungeon is typically the heart of the region’s specific problems and Sumo must inevitably visit it to kill the local monster and unlock the macguffin he needs to progress. Some dungeons provide unique obstacles, like runaway minecarts in the Old Mine and a maze-like portal network in the Temple of Mana, but most are studiously interchangeable.

The dungeons are where Final Fantasy Adventure most feels its age. Many dungeon doors are locked and require a key to open, which drop from skeletons or can be purchased in shops. Any key will open any dungeon door, but they are single-use. It’s frustrating having to stop and backtrack to find skeletons to kill, or worse return to town, because I didn’t stockpile enough keys to open all the doors in the coming dungeon. The designers did have enough foresight to include at least one room with skeletons in every dungeon, even the final dungeon when shops are no longer accessible, but this does not mitigate that locked doors are meaningless roadblocks which only frustrate me and do not add depth to the experience. There’s a similar system involving mattocks and breakable walls, but an indestructible morning star I find about halfway through the campaign nullifies its frustrations.

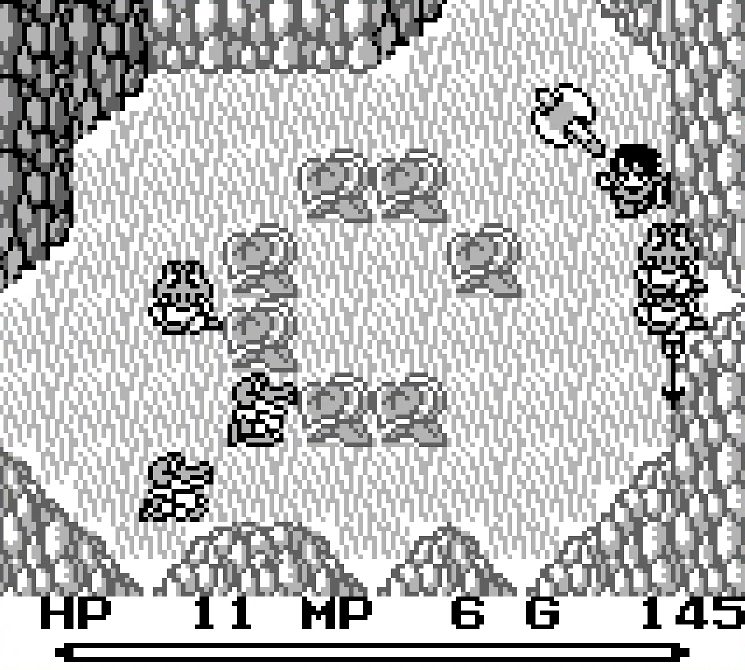

Worse still are the pressure switch puzzles. Some dungeon doors are sealed until one or more switches on the floor are weighed down by a heavy object. These switches mean it’s time to use the Ice spell, which sends out a frozen shard I can steer with the D-Pad. When the shard strikes an enemy they turn into a snowman, which I can push onto a switch to activate it.

This is a clever puzzle idea on paper, but random enemy movement makes it a chore in practice. Since snowmen are “killed” in one hit, I first have to clear the room of every enemy but the ones I want to freeze to ensure snowmen are not destroyed in the crossfire. This means a lot of waiting for enemies to move into a position where they may be killed one at a time. Since snowmen further cannot be pulled, only pushed, I have to wait until enemies are not standing near walls or in corners before freezing them. This means more waiting, and careful timing from the slow-moving Ice projectile. If I mess up on either condition, I have to leave the room and walk several more rooms away to compel enemies to respawn and try again. All my most frustrating moments with Final Fantasy Adventure are spent trying to use Ice magic to activate switches.

Final Fantasy Adventure lays the groundwork for the action-RPG design the Mana series would become famous for in its 16- and 32-bit sequels, but I feel its age. Enemy AI is non-existent, making combat feel like dodging an avalanche instead of fighting an army intent on Sumo’s death. It’s not always clear how to progress in the story. Dungeons become frustrating to navigate, putting up roadblocks that utilize unnecessary or underdeveloped mechanics to pass.

Despite these issues, I still feel affection for Final Fantasy Adventure. Its world is impressively realized, especially for the Game Boy hardware, predating Link’s Awakening by two years and Pokémon by five and in some ways still surpassing them in scope and direction. As the root of the Mana series, as an early example of an action-RPG, and as an early Game Boy RPG, it’s worth experiencing if you go in knowing what to expect.