Neo Cab is a narrative mystery videogame about the ways technology changes and complicates the world and relationships we share. I play as Lina, a driver for the rideshare app Neo Cab who has moved to the tech metropolis Los Ojos. Already resentful about moving to the hometown of Capra, the megacorp that laid Lina off from her last driving job, the situation is made worse when Lina’s friend Savy disappears before she can move into their apartment. The only clue to Savy’s disappearance is a shattered cell phone stamped with the emblem of Radix, a Neo-Luddite movement that protests Capra’s ever-increasing influence in Los Ojos. Over the course of this five to ten hour story, I help Lina select and interact with her fares, manage her money to survive another night, and solve the mystery of Savy’s disappearance in a city swallowed by technology.

I spend most of my time in Neo Cab talking with passengers Lina transports as part of her job for the titular rideshare app. This happens in the familiar back-and-forth dialog exchanges of contemporary narratively-driven videogames: The passenger says something, I choose how Lina responds, the passenger’s feelings about Lina change based on my choice, and their subsequent reaction gives me more choices to make. We go back and forth until the conversation ends, conveniently as we arrive at the passenger’s destination.

Each potential passenger is a conduit to explore a particular issue caused by a hyper-technological world. My first fare is Liam Baird, a hobbyist photographer taking a break from his “real job” to see if he can turn his hobby into a career.

As my first passenger and a fellow-newcomer to Los Ojos, I felt a particular connection between Liam and Lina and kept picking him up when his face appeared on the Neo Cab app. When some of his photographs go viral on Capra’s social media platform, we indulge in conversations about ownership. Does the picture belong to Liam, who took the picture, or to Capra, who provides the picture with a platform? Is the meaning we interpret from a picture more important than who gets to monetize it? Is a picture’s meaning changed by the way it is distributed? I choose options that encourage Liam’s talent and authorship, he and Lina become firm friends, and his newfound social media virality proves pivotal in the plot’s climax.

Another character who creates conversation about how technology affects our lives is Fiona Pak. When I first meet Fiona, she is on the way to meet her boyfriend, Dre, for the first time; until then they have only spoken online with Fiona always hiding her face behind a filter.

Our first conversation is all about Fiona’s self-consciousness, about the validity of online relationships, and the veracity of the nano-machine enhanced makeup she applies to resemble the face that Dre knows from Fiona’s vidchat filter. When I pick her up again a few nights later, I learn she is letting an algorithm decide what she and Dre will do next. Fiona, while not thrilled about the algorithm’s choice, goes along with it because she trusts it more than she trusts her own feelings.

I see a lot of how we exist on the internet through Fiona. I see the identities we put forth online which clash, or even contradict, our offline selves. It’s easy to subsume ourselves in these online identities, which are no more or less real than our flesh-and-blood ones, though that subsumption exposes all facets of ourselves to technological manipulation. Fiona doesn’t want to go dancing, but it’s easier for her to give in to what an algorithm predicts Dre will like than to have a real conversation with him about her wants and needs. I don’t want to watch a YouTube video about the latest viral scandal, but it’s easier to let it play than decide what I would actually enjoy watching.

Not every passenger in Neo Cab is a portal into a philosophical discussion. Some passengers offer scenes that are more slice-of-life, comedic, or even downright meta.

On Lina’s fourth night in Los Ojos, I pick up a pair of German tourists who believe Lina is a robot installed to put passengers at ease while a Capra AI drives the car. When I protest this assumption, they subject Lina to a Turing Test filled with inappropriate sexual and moral questions. Their tone is so flat and tactless that I start to wonder if they are robots . . . then I remember they are non-player characters in a videogame, and no matter how genuine my conversations with Liam and Fiona may feel, they are no more “real” than this pair of automaton tourists. Whether or not Klaus and Marek are robots is mostly an academic question; in Neo Cab, all my fares are robotic.

I must be careful about how I interact with Lina’s fares as each one gives her a rating when they arrive at their destination. The Neo Cab app relies on these ratings to determine who they will contract with, kicking anyone who drops below a four-star rating off their driver network. It’s not difficult to stay above four stars—the videogame wants me to stay focused on the story more than it wants to give me a game over screen for antagonizing a passenger.

The star rating does create a metaphorical roadblock when a passenger with key information about Savy’s disappearance will only accept Lina as their driver when she has a five-star average. Since I disappoint a quantum mathematician with some pedestrian answers to her philosophical questions, I have to spend an extra night building Lina’s rating back up before I can continue the plot. If I were in a hurry to finish the story, this might annoy me. Luckily, I find Los Ojos’ many passengers interesting, well-written, and engaging, so I am not in a hurry.

It’s not always possible to be careful when interacting with a fare. Lina’s exchanges with the people of Los Ojos can leave her feeling angry, sad, or happy, and particularly profound expressions of these emotions can lock me out of certain dialog choices or force me into others.

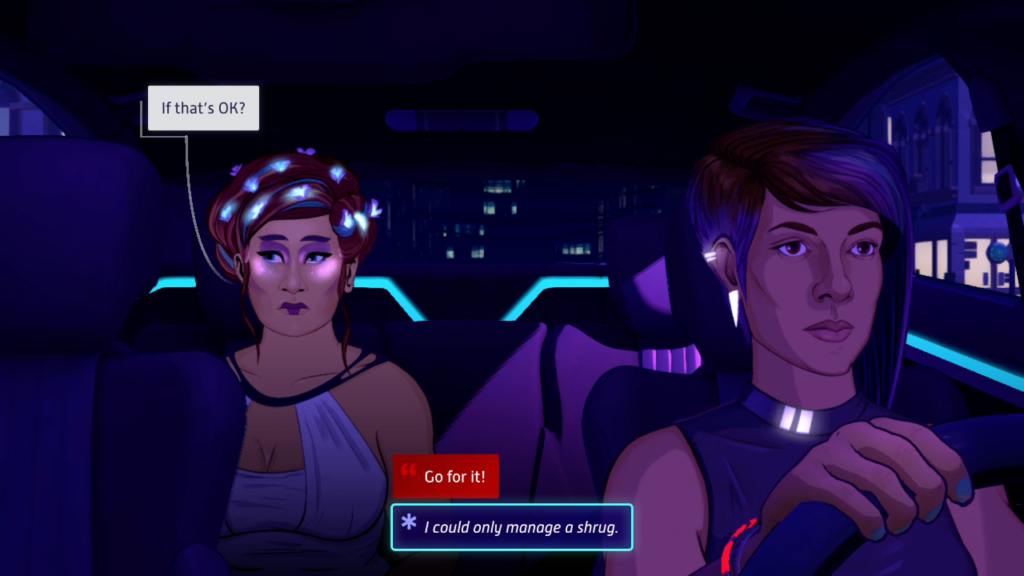

When Lina first meets Fiona it is straight after a frustrating encounter with a nightclub bouncer that leaves her feeling angry. When Fiona reaches out to Lina for support, I try to direct Lina to act open and interested in her problems and not as a dispassionate chauffeur only interested in collecting a fare. Lina’s lingering anger leaves her too irritated to emit the cheery “Go for it!” I want to select, forcing me to select the emotive I could only manage a shrug instead. Luckily, Lina realizes her mistake and Fiona lets the dismissive behavior slide after an apology. There are other conversations where being forced into or out of certain responses don’t end so happily.

Lina’s emotions are represented visually by a color spectrum called a “Feelgrid,” a high tech mood bracelet which is always visible on her wrist. The bracelet’s lights change color depending on how Lina is feeling: Red for anger, yellow for happiness, green for relaxation, and blue for sadness. The more vivid the color and the more lights it occupies on the bracelet, the more choices I will be forced into or out of while interacting with a passenger.

Lina’s emotions, as represented visually by the Feelgrid, put an interesting twist on conventional narrative mechanics. It is typical in these videogames for dialog choices to begin from a neutral standpoint regardless of what has just happened in the plot, allowing me to direct the player character to ricochet between emotional extremes in conversation. Any possible logical flow is dependent on the designers providing options that feel natural in the moment, and depending on the complexity of the dialog trees this flow can be difficult to maintain for long periods of time.

The Feelgrid, by allowing me to see certain responses while also locking me out of them, provides a glimpse at what could be if Lina is having a better night, but forces me into rash or tactless responses. I love seeing a system that forces me to more fully exist within the player character. Rather than trying to game every conversation by picking the most conciliatory option, or automatically moving up or down to the Heroic or Antiheroic option, Neo Cab forces me to empathize with the player character’s emotional state as well as the non-player characters’. It helps to make Lina seem more fully-realized in a medium where player characters can too often feel like blank abstractions.

Regardless of whether I let Lina’s emotions get the better of her and tank her star rating for that fare, she will earn some money called Coin for completing a delivery. Homeless and reliant on her car to earn a living in Los Ojos, I must conserve Lina’s Coin so she can charge the car’s electric battery and rent a hotel room every night. Before I pick up a passenger I can see how much battery power the trip will use up and there are charging stations dotted all across the city, so I never felt in danger of Lina’s car dying mid-trip.

Renting a hotel room is a little more complicated. There are only a few hotels around town, and most of them are Capra-run “sleep pods.” There are two other options: One costs more Coin to rent than I ever hold at once, a nice touch that emphasizes the class divide Lina lives in. The other non-Capra hotel is often on the other side of Los Ojos from my night’s final fare, forcing me to spend extra Coin recharging Lina’s car if I want to defy Capra’s near-monopoly—but that Coin always goes into a Capra-owned charging station, making my resistance token at best. These choices subtly bring home the futility of protesting with my dollar. In a hyper-capitalist city ruled by a tech monopoly, my money unavoidably ends up in the coffers of companies I do not like.

As I work through the nights, Lina’s stored Coin dwindles no matter how much she earns from her fares. Between charging her car, renting a room to sleep, and the occasional fine or bribe paid to Los Ojos’ mirror-faced police force, it seems inevitable that she will go bankrupt. It feels like there is a soft cap on progression: Finish the main story before Lina’s Coin runs out, or face the living hell of being broke, homeless, and unemployed in a corporate tech oligarchy.

Despite being a relatively low-budget indie videogame, Neo Cab finds effective and simple ways to portray Los Ojos. If I look out the windows of Lina’s car, I can see the Los Ojos streets zooming by as she drives to her next destination. These streets are lightly decorated and darkly lit, giving a sense of setting rather than place; whether Lina is driving through Liberty Heights in the north or Frontera in the south, the streets appear the same. This forces me to take Neo Cab’s word for the setting’s grandeur: Liam gushes about Capra’s impressive headquarters; I never get a clear look at the building even when Lina’s job brings her to its doorstep. If I were to spend all of Neo Cab staring out Lina’s window I would get the impression she is circling the same few city blocks over and over.

I am not staring out the windows, I am looking at Lina and her passengers. They are represented by simple polygonal models decorated by intricate sprites to represent the features of their face. These sprites are superbly animated, capturing clear expressions of contempt, delight, and melancholy through the subtlest change in their eyes and forehead. Even though Lina is equipped with a piece of tech that communicates her feelings through colored lights, I don’t need the Feelgrid to recognize those emotions. The same goes for her passengers.

Where I feel Neo Cab’s budget is the character’s voices, or lack thereof. There is no voice acting to speak of, so the expansive script is displayed on screen with speech bubbles. This means my eyes are constantly shifting between the speech bubbles to read the next dialog and then back to the character’s face to evaluate their emotions. I wish I could stay locked on those wonderful expressions, but it’s a necessary compromise and the effect still works well.

Neo Cab is a smart and timely mirror on how technology impacts our lives. Los Ojos is a brilliantly realized environment, futuristic with its holographic smartphones and its fleet of AI-powered taxi cabs, though grappling with the same moral and ethical issues we confront in our own world. It has a lot to say about these issues, exploring them through engaging Socratic dialogues. Some of its especially contrived systems don’t work as well as its narrative—maintaining Lina’s star rating and spending her Coin feels obligatory, arbitrary, and ultimately futile—but they are easily muscled through and add another layer of depth to the social commentary. Overall it’s an excellent narrative experience.