My first years playing videogames were spent with NES titles like Demon Sword and Ninja Gaiden, action-platformers with a distinct 1980s aesthetic of stoic, bare-chested beefcakes saving the world by murdering a lot of faceless mooks and their cultural stereotype commanders. I retain fond feelings towards these videogames, but they were only enjoyable with a Game Genie and my nostalgia tends to exclude that part of the experience. Enter Oniken, a videogame developed in the 2010s for people who played videogames in the 1980s, capturing the 8-bit action-platforming era’s essence but smoothing over the flaws nostalgia tends to overlook.

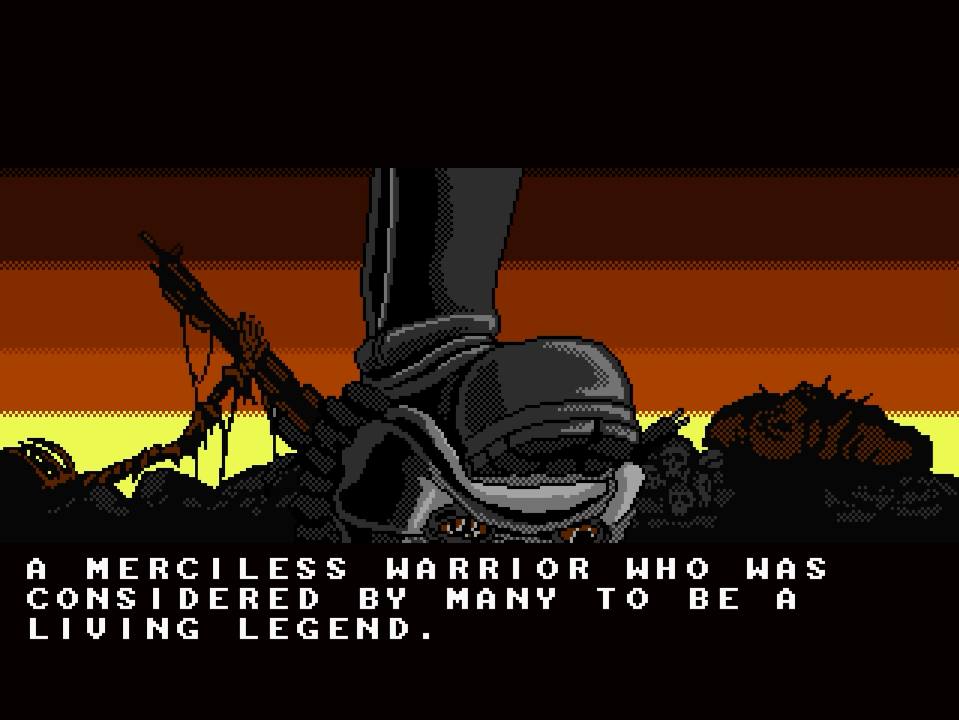

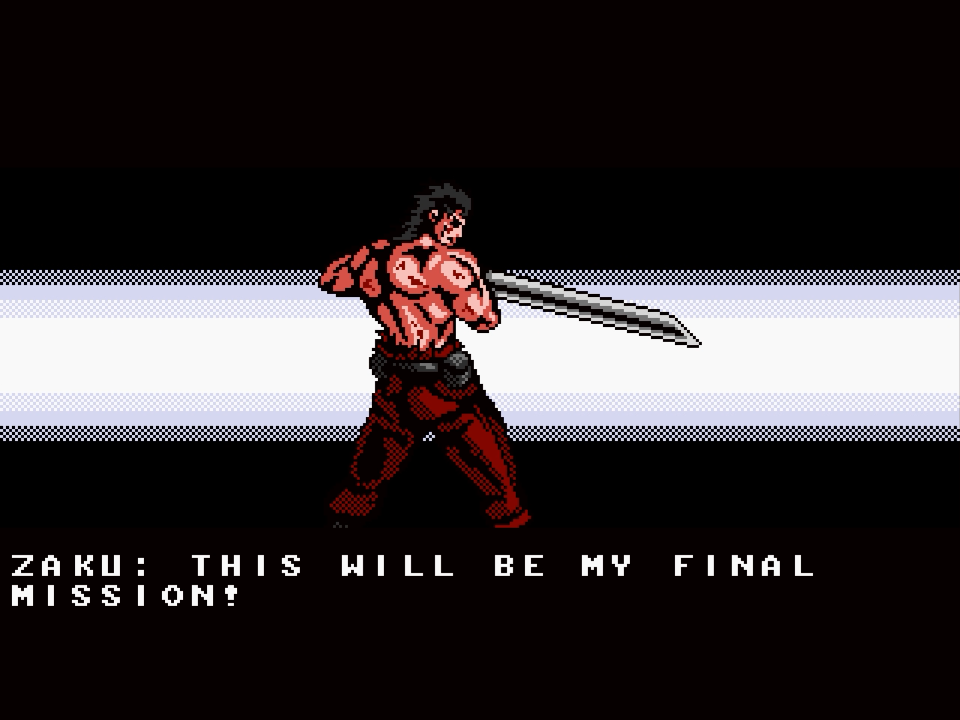

Oniken is the 1980s distilled, homaging the most iconic films from that decade. It is the year 20XX, and following an apocalyptic war the world is ruled by the Oniken and their army of bio-mechanical monsters. The Resistance recruits a legendary mercenary named Zaku to assault the Oniken army and assassinate its leaders. Oniken is one part Escape From New York and one part Terminator and is unashamed of that fact.

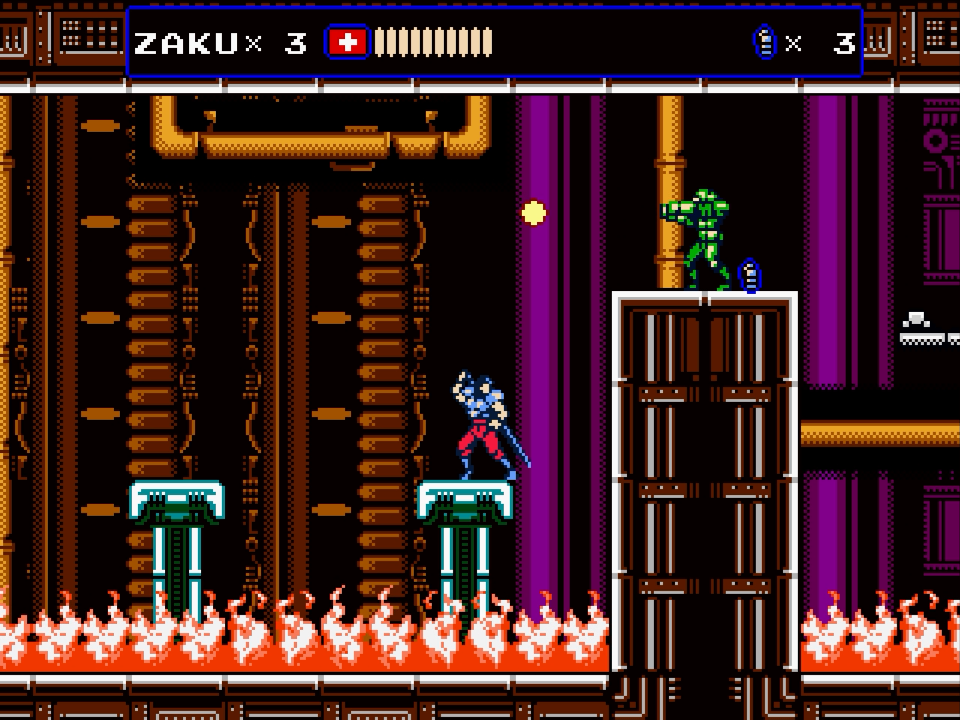

Zaku is a straightforward 1980s action-platformer protagonist. He runs, he jumps, he climbs, he swings a sword. He throws grenades found stockpiled throughout the levels, though I sometimes struggled to get this ability to activate. Zaku also finds a powerup that lets him hurl waves of energy from his sword, but he loses it upon taking damage. I may also direct Zaku to consume this powerup to become an Oniken-annihilating berserker for several seconds. This ability can decimate bosses . . . if I am able to navigate entire levels without taking a hit. Oniken rewards knowledge and precision, and has the level design and input sensitivity to allow it.

Zaku’s mission takes him across six levels. Each level is divided into three short acts, and each act offers something new. One pits Zaku against a team of hit-ninjas on the back of a train. Another has him climbing along poles suspended above a devastated cityscape. Several acts put Zaku on the back of a hoverbike, blazing towards his next goal (or away from an angry polar bear) with guns firing. Late on, Zaku penetrates the enemy headquarters through the barrel of their superweapon, hiding in nooks and crannies to avoid periodic superlaser blasts. Oniken’s short length is a strength, ensuring I am always doing something new and ending before repetition sets in.

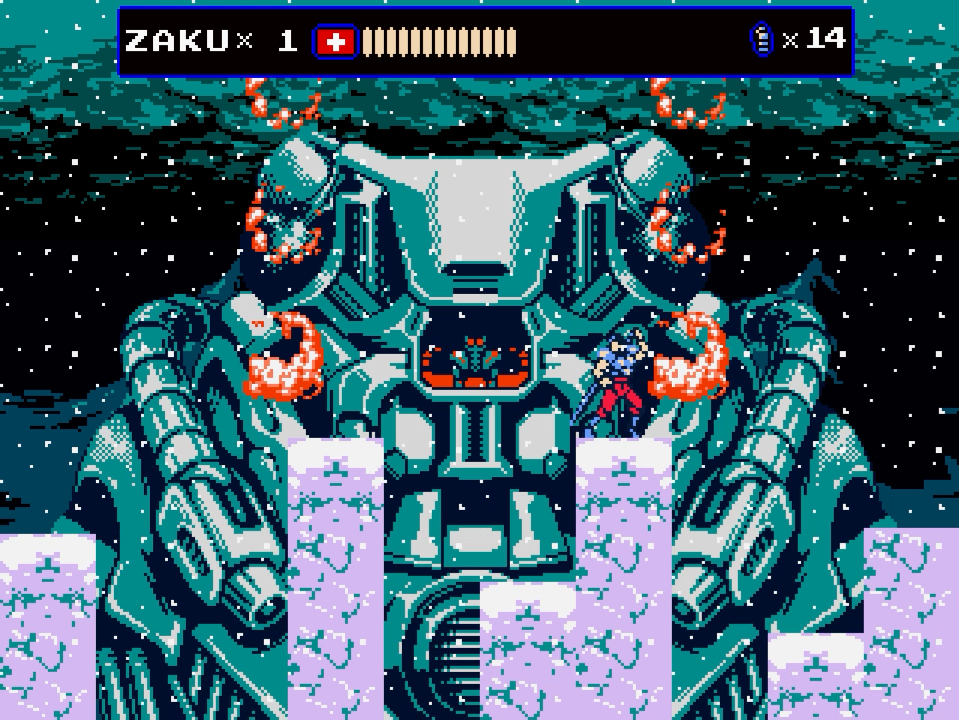

Each act culminates in a boss fight, sometimes simple, and sometimes a multi-phase brawl that requires several attempts to learn and clear. One boss is a mech that fires missiles at Zaku while he jumps between mountain peaks, the safe platforms beneath his feet worn further away with each bombardment. Another is a gigantic centipede that lunges from the screen corners, trying to crush Zaku with its pincers or immolate him with flames. Checkpoints are set at the beginning of acts and not before bosses, but I found the acts short enough that this didn’t frustrate me much. The exception is the final level, where bosses make a disconcerting jump in difficulty, but I was able to overcome them with determined persistence and beating Oniken felt all the more rewarding for it.

Oniken captures an effective 8-bit aesthetic, but goes overboard with the flourishes. Visuals default to a stretched 16:9 image and have a crude CRT scan line overlay. Both of these options can be turned off in the options menu, revealing the proportioned and crisp pixel art underneath. I also caution interested players that several cutscenes feature strobing light effects. I do not have photosensitive epilepsy, but I am concerned for those who may get a nasty surprise from Oniken. Some aesthetic flourishes are better left in the 1980s.

Oniken reminds me of the sword-swinging action-platformers I played in my youth, but with an important distinction: I was able to finish it. It has the aesthetics of those videogames, but none of their frustrating design. A bird does not appear in front of Zaku just as I make a do-or-die leap to the next platform. Lives are limited, but continues are infinite and never set me back further than the beginning of a level. The flickering and slowdown that would bog down a similar NES videogame are nowhere to be found here. Oniken is the classic 80s action-platformer as I like to remember it, not as it was. I enjoyed it, and if you have the same nostalgia as me, I expect you will too.