From its eponymous debut in 2007 to the release of Syndicate in 2015, ten core Assassin’s Creed entries were released and it didn’t do them any favors. With development focused on annual iteration instead of total innovation, the parkour systems that allowed player characters to bound through dense cities and tangled forests felt more clumsy with each installment. This culminated with Syndicate introducing a train that let its protagonists zoom through the environment on rails instead of run and a grappling hook that let them glide up buildings instead of climb; after eight years, Assassin’s Creed’s biggest ideas were to make its main claim-to-fame optional. The series needed a retool instead of being bigger versions of last generation’s entries, a retool that finally came in 2017 in the form of Assassin’s Creed Origins.

Assassin’s Creed Origins is the story of Bayek of Siwa. Bayek is the last Medjay, a royally-appointed order of warriors who disappeared after the fall of the New Kingdom that ushered in Egypt’s Ptolemaic dynasty. The Ptolemies rule an Egypt in decline, the Great Pyramids neglected and crumbling into the desert sands and government institutions intertwined with the Roman Empire. Bayek and his wife Aya live a happy life away from the political intrigue in Alexandria and Thebes, raising their son Khemu in a small town called Siwa. But then a cult called The Order of the Ancients raids Siwa’s temple and Khemu is murdered, sending Bayek and Aya on a quest for revenge that will upend Egypt and Rome and birth a brotherhood of assassins.

This premise seems like fertile ground to challenge what past Assassin’s Creed videogames have been: It’s set more than one thousand years before the next-earliest series entry; Bayek is the first player character with no European heritage; and, of course, there is no Assassin’s Brotherhood to challenge the Order of the Ancients.

In a game with “Origins” in the title I expect the Brotherhood’s founding to form the plot’s backbone, but it does not. Even as Bayek’s quest has him getting up to all sorts of assassin-like exploits, it is a solitary one, his friends and allies acting more as quest givers than potential recruits. They do join together in the ending cutscene to form an early Brotherhood cell, but it’s never a goal in the story itself, most of an origin story’s work happening off-screen and post-credits. Even the Hidden Blade, the Brotherhood’s iconic weapon, appears wholly-formed in an early quest, its creation predating the Creed by centuries. If Origins is an origin story for the Brotherhood, then it’s a bad one.

More frustrating is how derivative Bayek’s story is of Ezio Auditore’s. Like Ezio, Bayek’s journey is kicked off by the murder of his family. Like Ezio, he learns to use an assassin’s tools to avenge his son. Like Ezio, he finds that the price of revenge is his soul. Bayek’s enemies even suffer from the same problems as Ezio’s: They are introduced and then killed so quickly that it’s difficult to see how they tie into the conspiracy the hero is unraveling, devolving into a cadre of random folk performing random evil so I don’t feel bad about stabbing them then moving onto the next. Origins kicks off with a powerful, tragic murder, then consistently fails to create catharsis for that moment as it overwhelms me with mechanic-driven assassination targets and irrelevant sidequest filler.

With a new era of Assassin’s Creed videogames comes a new play style. It allows for many of the same exploits as past installments, but with renewed mobility. Holding down the right trigger to compel Bayek to run and climb is a relic of the past; now his speed is affected by the angle of my joystick movements, just like a 3D platformer, and he climbs cliffs or walls when I tell him to jump into them. Climbing is refreshed as well. Bayek still needs handholds to clamber up surfaces, but they are seemingly everywhere, allowing me to find my own way to the top of most structures rather than following a prescribed path. This freedom of movement feels new and contemporary in ways Syndicate and Unity’s attempts to streamline movement failed.

The second smart departure from established Assassin’s Creed conventions is the importance of vantage points. In previous entries, my first goal in a new area is to climb to the local vantage point, typically placed at the top of a building or cliff, and press the context-sensitive Synchronize button. This fills in the local map and all its activities which can be completed for small rewards. Rinse and repeat dozens of times across all environments. This design ruled Ubisoft-developed sandboxes and beyond for over a decade to the point of eye-rolling ridicule from players and critics.

In Origins, Vantage points still exist but their function is changed. Rather than revealing all the activities they instead mark points of interest with question marks, letting me know that something is there but not what it is, leaving at least some sense of mystery and discovery intact that the old system squandered.

Vantage Points also incrementally improve the vision of Bayek’s eagle companion, Senu. Refining the x-ray-like Eagle Vision ability from older titles, Bayek shares a psychic connection with Senu and can use her vision to scout the immediate area, marking enemies—which remain visible to Bayek, even through walls—and chests or valuable artifacts. Senu’s vision is rudimentary at the outset, but after synchronizing with dozens of vantage points she can see through walls and into buildings and even into the caves and tunnels running beneath Egypt, marking entire groups of potential threats and rewards with a single pan across a stronghold.

If any system in Origins could be said to be completely reimagined instead of refined, it’s the combat. Previous Assassin’s Creed entries were infamous for their absurd sword fights, every alerted enemy surrounding the player character then attacking one at a time. This made it simple to defeat them with simple-but-lethal counter attacks, each opponent seeming to volunteer to be another corpse crammed one at a time into a clown car of death.

Enemies in Origins happily gang up on Bayek in pairs or more. I can counter these tactics by playing defense with Bayek’s shield, deflecting lighter enemy attacks entirely or, with exact button timing on my part, even parrying enemy attacks and responding with a counterattack. These are powerful and useful, but instant-kill counters are a thing of the past. If I want to kill one of Bayek’s opponents, I need to claim every one of their hit points in skillful combat.

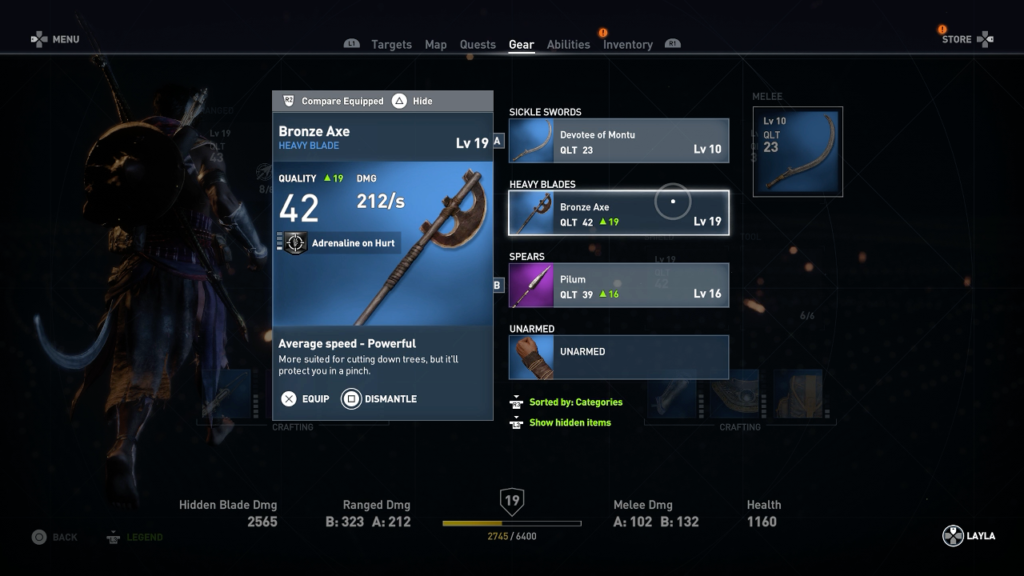

Origins also adds far more weapon variety to Assassin’s Creed. Equipment with randomly generated attributes is earned from map objectives or claimed from slain enemies. Bayek’s style of attack changes depending on the type of weapon equipped: sickle swords give him the ability to spin enemies around, exposing their vulnerable backsides for powerful critical hits; spears are slow to swing but have great range, letting Bayek keep powerful enemies at a safe distance; warrior bows fire a cluster of multiple arrows at once in a wide cone; light bows fire arrows at rapid speed in succession; and many, many more weapon varieties.

Origins’ combat is the system most transformed from past Assassin’s Creed convention and the one that needed it most. I do still prefer the older system because counterattack trains are a fun and easy way to get out of combat—no matter the incarnation I’m not playing this series for its fighting mechanics—but it’s impossible to deny that Origins’ combat is far more challenging and engaging.

While Origins feels better to play than its predecessors and puts serious effort towards overhauling their most rote design conventions, it is still an Ubisoft sandbox, succumbing to the foibles that trouble the vast publisher-developer’s assembly line philosophy of videogame development.

Egypt is a vast and vibrant sandbox, diverse metropolises flowing into the fertile Nile Delta farmland and onward into rocky deserts guarded by remote military outposts. Strewn across this sandbox are hundreds of activities which yield small rewards when completed. These activities range from hunting the alpha of an animal pack to claiming treasure from a guarded camp. While they are interesting at the outset, they succumb to quantity and repetition. Some activities keep their luster for the duration, especially the large military bases which present unique infiltration challenges, but there’s functionally little difference between the first military boat I infiltrate and the thirtieth, and there always seems to be at least one more lurking somewhere on the map.

Visiting every waypoint in every region is a daunting task but necessary to keep Bayek competitive with the next tier of enemies he will face in the story. There are sidequests where Bayek helps a character with a specific problem, but these are few and unmemorable and drowned out by the sheer number of trademark Ubisandbox activities—and they often task me with completing yet another map activity I was going to do anyway. This Assassin’s Creed sandbox might control better than others, but in terms of tedium it feels very much like its predecessors, the entire experience swirling together into a slurry of vague saminess.

Origins doesn’t only feel like an old Assassin’s Creed experience in a broad sense but in specific ones too. A common experience I have in the older-style entries is to creep through an enemy camp, assassinating targets along the way, until I inevitably get hung up by some movement quirk or awkward geometry and get spotted by a guard. The guard alerts the rest of the camp and I have to fight them all. The same thing happens to me in Origins. Even though movement is smoother and combat is deeper, making Origins feel like less a relic of late-00s videogame design, the essence of Assassin’s Creed, flaws and all, remains at its heart.

All of this means that Origins won’t alienate committed Assassin’s Creed fans, but it also means it may not draw in disillusioned former players or disaffected new ones. For a player like me for whom Syndicate was close to the tipping point, Origins is more of a bandage: At first the scale of the world and the refined movement is exhilarating, but after a few hours I realized I was up to the same old Assassin’s Creed filler as before and had far more space and time ahead of me than even the most ambitious previous entry.

Origins’ daunting scale and insidious saminess makes spending prolonged time in this Egypt a displeasing notion, but enjoyable enough for short visits—again, much like past Assassin’s Creed entries. But after many dozens of hours I encounter new enemies that send me rushing for the end credits.

Incredible though it may be to believe, Assassin’s Creed Origins features powerful late-game enemies immune to assassination. I can try to assassinate these elite commanders, but they ignore the thrust of Bayek’s Hidden Blade and drag him into combat, forcing me into situations I don’t need to be in with combat systems I tolerate at best. Standing a chance against these powerful enemies necessitates clearing out the rest of their often-massive strongholds—difficult enough to do without being spotted—and if I get Bayek killed in the final battle with the elite commander I have to clear the entire base over again. It’s horrible, and within hours of encountering these situations I resolved to quit scouring this ambitious Ubisandbox and sprint to the end credits. I was so lost in innumerable activities at this point that that I wasn’t invested in the plot anymore and barely remember its closing moments.

Despite the steps taken to improve systems that have become rote, even cliché, Assassin’s Creed Origins still doesn’t feel like a big enough step away from the repetitive design elements that belabors previous series entries, and indeed, Ubisoft sandbox videogames writ large. The series needs more than new ways to interact with its main plot and sundry activities, it needs new ideas. Despite setting itself up in all the right ways to explore new ideas, they aren’t here. Origins lays the foundation for a new Assassin’s Creed generation, but it doesn’t quite get there itself.