The Messenger is a retro platformer about a delinquent ninja charged with delivering a scroll to a distant mountain peak in order to fulfill an ancient prophecy that will save the world. It is the distant future, and humanity has been driven to near-extinction by an invasion from Hell. The last survivors have taken refuge in an island village, training themselves as ninja warriors in preparation for the day the demon army will return to wipe out humanity for good. The demons’ arrival is said to be heralded by a hero arriving from beyond the western ocean who will confer upon one of the ninja a magical scroll that will be the key to victory.

I play as a young ninja who is frustrated with his disciplined life and skeptical of the prophecy they all await . . . until the hero suddenly arrives and hands a scroll to the young ninja just as the demon army appears. I must guide this ninja, now the appointed Messenger, across his besieged island home to fulfill the prophecy and save what remains of humanity.

The Messenger appears to be an unremarkable retro platformer. The Messenger himself is blatantly styled after Ryu Hayabusa, quintessential ninja protagonist of the 8-bit Ninja Gaiden platforming trilogy who also wears a dark blue tunic and hides his face beneath a cowl. He even handles much like Ryu, able to run across the screen in seconds, make fast and precise jumps between platforms, and attack enemies with quick strikes from his sword.

It’s in every other way The Messenger moves that makes him unique. At milestones along his journey he receives new tools to aid his traversal over increasingly treacherous terrain. A set of claws let him cling to and climb up and down walls. With a rope dart he can pull himself towards walls, targets, and enemies. A wingsuit lets him glide across long gaps, or ride up wind currents to new heights.

It’s The Messenger’s first ability which makes him truly stand out among the crowd of ninja-themed platforming protagonists. His clan practices cloudstepping, a technique that allows them to jump off thin air after striking an enemy or object with their sword. This ability is so important to progress that I am expected to demonstrate a basic level of competence with it in the first level before the demon invasion even begins.

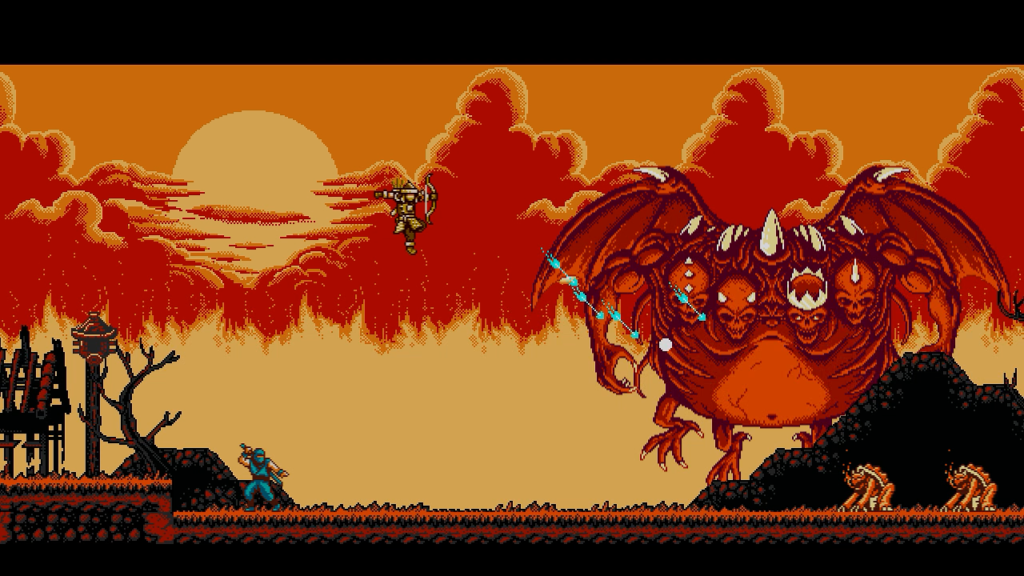

At first cloudstepping feels awkward—it’s essentially a double jump that requires an extra step before the second jump can be made—but before long I’m using it to cavort The Messenger across long gaps between platforms. At the height of my skill and the videogame’s challenge, I use a string of cloudsteps to strike repeatedly at towering boss heads and propel along lines of enemies. It’s gratifying to experience such a simple twist on double jumping mechanics that makes me feel skillful without asking much more than an extra swing of The Messenger’s sword.

After cloudstepping, claw-climbing, rope-darting, and wingsuiting across a ninja village, a bamboo forest, a nasty swamp, a suffocating cave, and a barren waste, The Messenger scrambles his way to the mountain’s peak and encounters the big plot twist. This twist is revealed in much of the marketing and has become common knowledge among retro platformer fans. If you don’t know the twist by now and would like to experience it unburdened by knowledge, suffice to say The Messenger is a solid retro platformer with a few original platforming ideas it executes well. I recommend it, and you do not need to continue reading past this point. For the rest of you, I carry on with the review.

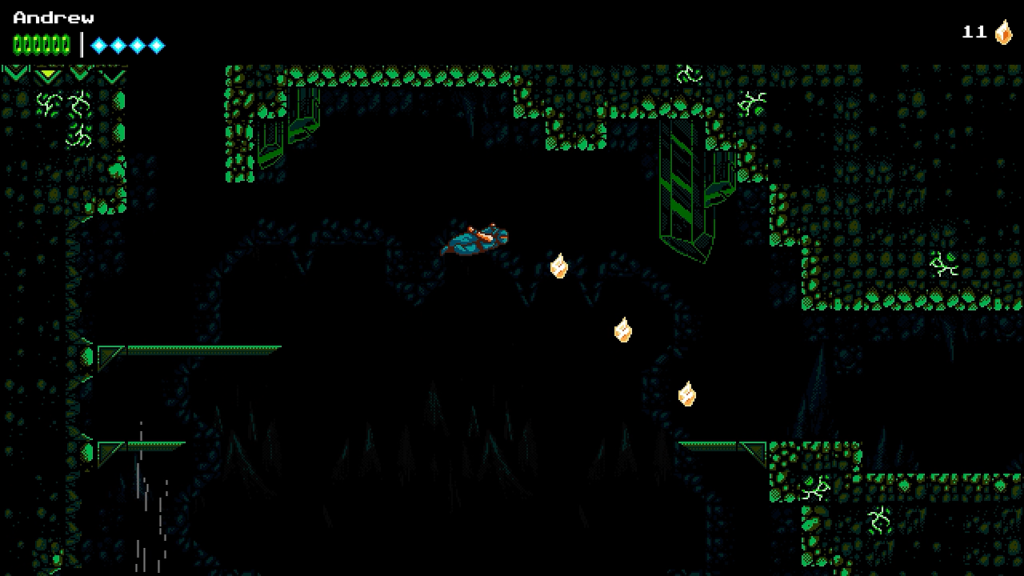

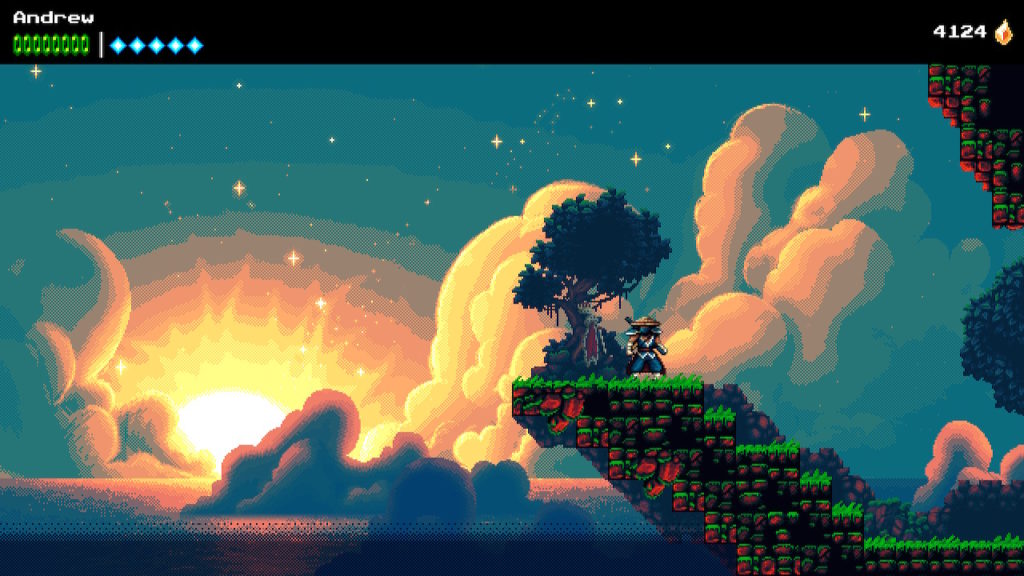

After completing his mission, The Messenger is transported five hundred years into the future. This transition is accompanied by an amazing graphical transition from a simple 8-bit color palette to a dense 16-bit one. Lightly-decorated black backgrounds are replaced by vibrant landscapes of sun-soaked clouds, fog-choked bogs, and the fiery caverns of Hell itself. Even the music seems to transport itself between ten years of videogame history, accumulating layers of instrumentation under its basic tunes. Witnessing this pivotal moment in The Messenger is like watching Mario transform in an instant from Super Mario Bros to Super Mario World. It’s an incredible experience for this fan of both classic and retro platformers.

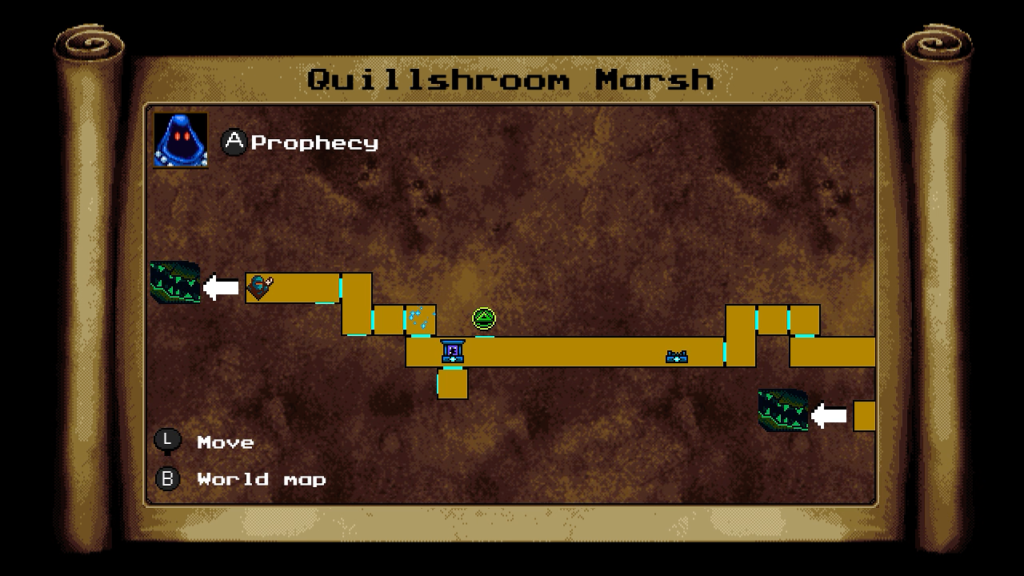

This transition is much more than graphical and aural. Though The Messenger’s mission is completed, a cosmic accident presses upon him a new task. He gains the ability to travel freely between all the previous levels which reveal new secrets thanks to The Messenger’s time traveling powers. The rigidly linear retro platformer where the only way to go is forward becomes an open adventure where going backward is also a viable choice.

The temptation here is to say that The Messenger “becomes” a non-linear platformer in the tradition of Metroid or Hollow Knight, but that would be giving it too much credit. Its structure is still based on linear levels which follow prescribed routes. The addition of time travel only allows more hidden areas to be accessed and a hub area lets a level be revisited as many times as I need to. Finding the correct order to enter all these side paths with the needed macguffins to complete them means I play some levels three or four times before I open every necessary door.

Luckily, The Messenger’s platforming mechanics are engaging enough that I don’t mind conquering its levels multiple times using my growing mastery of its systems. Just don’t believe that The Messenger turns into Metroid as I have sometimes read. It doesn’t do that at all.

Up until now I may have made The Messenger sound dour and self-serious. On the contrary, aside from expository scenes exploring the setting’s backstory, The Messenger is a laugh. A boss duo fought on a barren mountaintop are a cyclops pair named Colos and Suses. Obsessed with exercise, Colos has thick arms and six-pack abs but flabby legs, while Suses has ripped thighs and legs but a floppy gut. Their attacks reflect their apparent training regimens.

The Messenger is aided on his adventure by a shopkeeper in a blue robe who is fully aware she is in a videogame and hangs lampshades on almost every trope I encounter. There is a wardrobe in her shop she tells The Messenger will not open until later in the plot, and her growing exasperation with my repeated attempts to open it before that time is some of the best comedy writing I’ve encountered in a videogame. Writing jokes is hard, but The Messenger makes it look easy.

Humor also arrives in the form of Quarble, a demon with a magic ring who follows The Messenger on their journey. When The Messenger dies, Quarble resets time, returning them to the last checkpoint they passed. Quarble then hangs around for a few minutes hoovering up all the currency that appears until he’s satisfied. As Quarble explains, charging The Messenger for a chance to try again is more profitable than letting him die—but he will still feel the agonizing pain of every death.

This system uses dark humor to address a classic platforming difficulty problem. Many classic platformers have a reputation for grueling difficulty because of their limited extra lives. They would be enjoyably beatable if the player was provided with enough chances to learn their current obstacle without being sent back to the beginning of the level, or quite often the beginning of the entire videogame. It’s no accident that the most popular code on Game Genies and Game Sharks is for infinite lives and Rewind features are so prevalent in current emulation. Since Quarble saves The Messenger’s life, then charges him for it, I can retry a particular obstacle as many times as I need to.

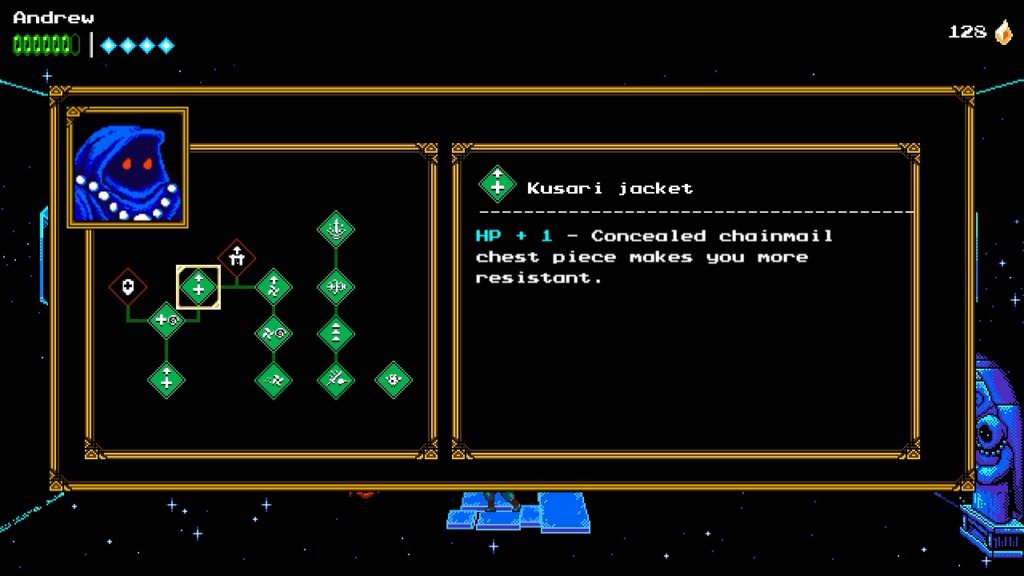

Despite Quarble’s snark, his service still applies a meaningful penalty: When he’s taking all the money that drops for a few minutes, then The Messenger isn’t accumulating currency to buy upgrades. It’s a harsh but fair tradeoff compared to being told “you suck” and having hours of playtime erased in an instant. And to be honest, Quarble’s fee is quite reasonable. I still come out the other end of The Messenger having purchased every upgrade with considerable resources leftover.

The comedic elements go for broke in Picnic Panic, a free post-credits DLC that sees The Messenger traveling to an alternate dimension to enjoy a picnic on a tropical island. The premise is absurd on its face; The Messenger already lives on a tropical island, so the whole trip is unnecessary. The first level is even a surfing level, parodying a weirdly prevalent trope in the 8-bit platformers The Messenger homages.

Things really get out of control when a villain from the main story reappears to disrupt the festivities. If I keep an eye out as I cloudstep through the three new levels I can spot him spying on The Messenger, popping his head out from behind bushes like Snidely Whiplash tracking the progress of Dudley Do-right. The whole farce ends with a colossal boxing match in the caldera of an active volcano.

Picnic Panic offers more challenge and laughs than the core videogame and unlocks a new difficulty mode when it is finished. Being free and clocking in at about two hours total, it’s a difficult offer to pass up.

The Messenger is an excellent and efficient retro platformer. Its varied platforming skills are applied in fun, intelligent, and unexpected ways. It’s a beautifully constructed world of classic pixels and synth sounds whether I’m witnessing its 8-bit past or 16-bit future. And despite its apparently somber subject matter, it’s also an uproarious parody of the kinds of platformers it’s putting to shame on a technical level. Don’t buy into the false hype that it’s a Ninja Gaiden homage that transforms into a Metroid homage, and you’ll have a great time with it. I definitely did.