Loop Hero is difficult to describe in a sentence. It is most clearly an RPG. I spend my time empowering the player character so he can endure the dozens of battles he will face in a single play session. It’s the various means I go about empowering that player character which makes it so unusual.

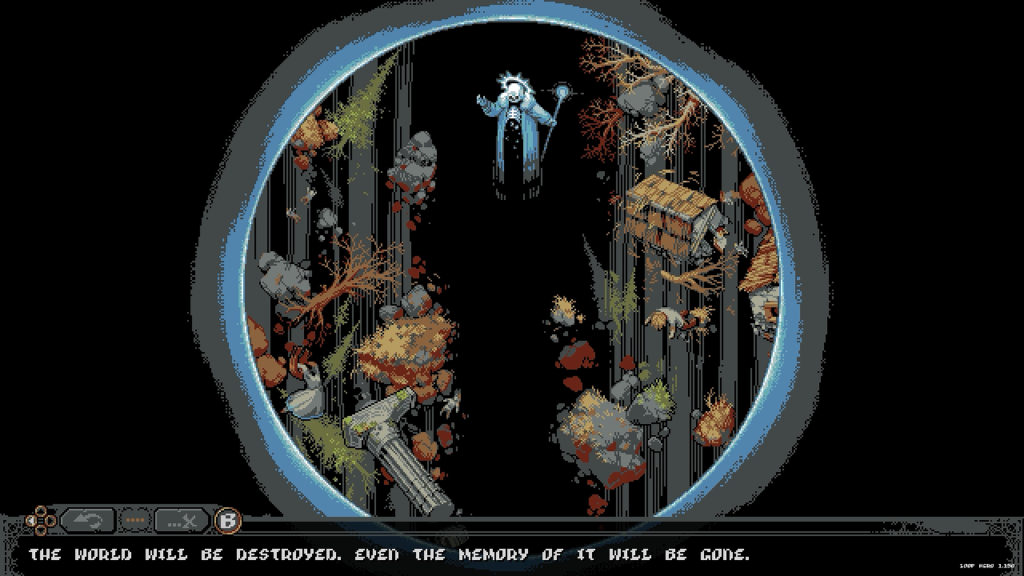

The player character is the Hero, a young man wandering a void after his world is consumed by a ravenous Lich. Nothing remains for him to experience; there are no oceans, rivers, forests, deserts, or mountains, no food, no light, and no people. Even his memories have been eradicated by the Lich. He only has an endless march through emptiness with a destination of nowhere.

Finally, the Hero stumbles across a camp which contains a few surviving humans on the verge of starvation. These survivors are unable to traverse the void, but the Hero discovers that he has the unique ability to follow a road that always loops through the void back to the camp. By using the survivors’ memories, the Hero can fill in the space around the looping road, gathering supplies to feed and shelter the survivors. But the more the Hero loops and improves the camp into a thriving settlement, the more he draws the attention of the Lich and its nihilistic masters.

Whenever I send the Hero out from the camp on an expedition, he will automatically loop a new road surrounded by empty grids on a map. Multiple times a minute an in-game day will pass and weak slime monsters will spawn on the road. When the Hero passes these slimes, he enters into turn-based RPG combat with them.

Combat in Loop Hero is entirely automated. The only input I have is the speed at which the battle takes place and whether the Hero runs away (whereupon the expedition ends and the Hero drops most of his gathered supplies). Between battles I can equip him with new weapons and armor that drop from the monsters he kills. The more loops he completes, the more powerful the monsters become, but so too will the quality of equipment they drop.

I must constantly evaluate whether the Hero’s equipment makes him strong enough to face another loop. When the monsters begin to overpower the Hero’s randomly dropped equipment, I must tactically retreat from the map to avoid losing his gathered supplies. If the Hero lucks into enough good equipment to let him endure enough loops, then he will face a powerful boss. When the boss is defeated then he can progress to a new chapter in the next expedition, where monsters will be tougher and a new boss waits to challenge him.

Yet sometimes the best equipment can’t save the Hero from his own incompetent decisions. Experienced RPG players will know that certain monsters should take priority in battle because of powerful effects they provide to their companions. It sometimes feels like the AI-controlled Hero attacks enemies at random. It’s frustrating watching his hit points get slowly whittled down as he attacks unremarkable basic enemies while ignoring the vampire lord providing hit point regeneration to the entire monster group. Despite this frustrating behavior, I can recall few instances of it outright losing an expedition for me.

There are three classes the Hero can become before he embarks on an expedition. When I begin Loop Hero he can only use the basic Warrior class, but over time I can choose to have him loop as a Rogue or a Necromancer as well. Each class has unique gimmicks which make them function differently from the others. The Warrior uses powerful defenses and life stealing effects to keep himself alive. The Rogue uses speed and evasion to kill monsters before he can get hit. The Necromancer summons skeletons to absorb monster attacks and overwhelm his enemies with sheer numbers.

I go through distinct phases where all three classes seem like the best choice for me, though ultimately I settle on the Rogue as my preferred class. Despite my preference, all of them feel viable. It’s simply a matter of learning which of their unique stats I need to build to give them the best chance at survival.

Aside from equipment, those basic slimes on a fresh road also drop cards. This is where Loop Hero becomes a much more interesting videogame about building fantasy worlds for the Hero to have adventures in.

Cards represent the surviving human’s memories of the world that was consumed by the Lich, coming in varieties from mountains to rivers to deserts. Which cards I place affects what kinds of enemies the Hero will face beyond the basic slimes. For every ten mountain cards I place on the map, a goblin camp will appear alongside the road and the Hero will have to face a pack of goblins each time he passes by.

Placing a card on the map not only changes the map for that expedition, but it also changes the Hero. Placing mountain cards may create powerful enemies to menace the Hero, but they also increase his hit points. Clustering mountains close together enhances the bonus, encouraging me to create massive mountain chains across one side of the world map.

This is how I discover that placing nine mountain cards in a three-by-three grid transforms them into a mountain peak. This new geographic formation offers an even greater hit point boost to the Hero, but also creates a harpy somewhere on the road every two days. There are many more interactions between different types of land cards which produce unique monsters and statistical bonuses for the Hero, and much of my enjoyment comes from discovering and exploiting these combinations.

The basic loop of Loop Hero is setting out on an expedition, killing slimes to get new equipment and cards, and through successive loops building a fantasy world for the Hero that becomes progressively denser with tenacious monsters to stand in his way. The type of world I build and the equipment which drop from monsters determines how successful the Hero will be at gathering its varied resources.

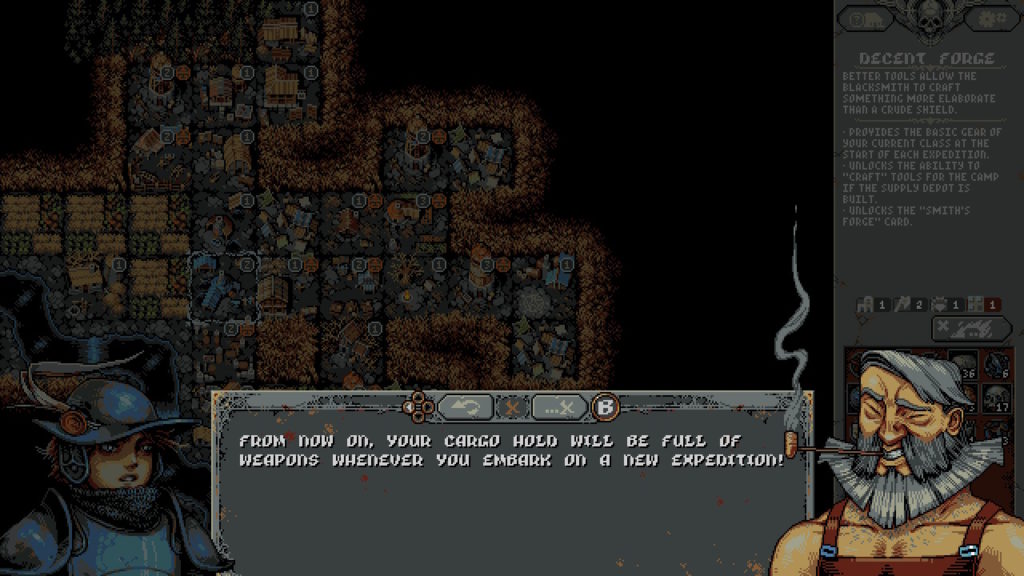

Resources are used to build up the survivors’ camp after each successful expedition. What I choose to build in the camp not only improves the survivors’ livelihood, it also provides permanent improvements for the Hero on future expeditions. An Herbalist’s Hut gives the Hero a fresh supply of potions on every loop to heal himself in battle. A War Camp increases the damage the Hero deals to monsters. A Refuge unlocks the Rogue class for future expeditions, while the Crypt unlocks the Necromancer class. Building and upgrading these structures is vital for the Hero to survive in later chapters when monsters gain powerful abilities that will crush a Hero just starting out into the void.

If I have a major criticism of Loop Hero, it’s that developing the camp to make the Hero strong enough to survive the later chapters feels like a real grind. Some structures take so many resources to build that it can take several expeditions to save up enough for the task. Going on a half-dozen expeditions over several hours without a single camp improvement to show for it creates a frustrating sensation of standing still. This frustration is especially true for the Orbs of Evolution. My stunted progress in the final chapter is a direct result of this resource, required in large numbers for most of the top-end structures, which feels aggravatingly rare no matter how many groves and spider cocoons I cover the road with.

Loop Hero thoughtfully conveys a world that has been turned into an empty void. Empty black space abounds, and quite apart from feeling lazy, it effectively creates a sense of all reality having been obliterated by the Lich’s magic. To avoid a jarring contrast to all this black emptiness, things which do exist are rendered in dark, moody colors. These visual choices create a somber atmosphere that captures the dark fantasy and cosmic horror themes well.

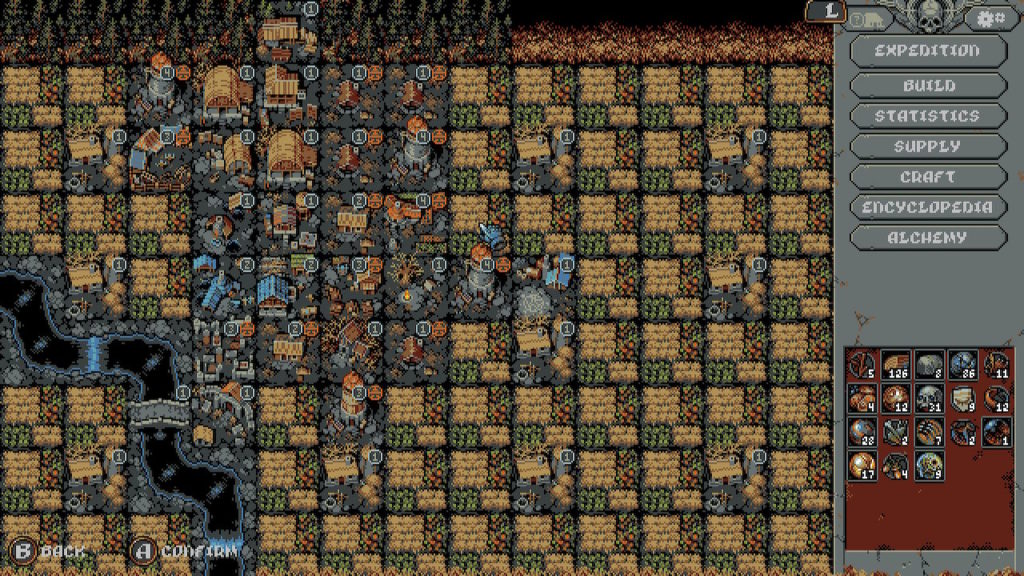

The exception is the camp. By presenting the camp from high overhead, buildings become minute with no distinguishing features, and when clustered together turn into a muddy blur of brown and yellow colors. I soon give up trying to recognize individual buildings. Instead I poke around the camp with the cursor, clicking each grid in turn, until the building I wish to interact with pops up on the right side of the screen. It’s an utter failure of an interface for a key feature that empowers the player character. It’s doubly disappointing since the maps I create on each expedition are much easier to read with many more clearly distinguishing features.

The choices made for Loop Hero’s music are especially interesting. It predictably uses 8-bit-inspired chiptune tracks to suit the pixel art graphics, but it also uses fewer sound channels than normal. This makes the music sound compressed and hollow, as though the Lich has consumed not only the physical world but also the sonic one as well. Only the Hero’s defiant march around the road keeps the music alive, struggling to break through the emptiness to be heard.

Loop Hero is an audaciously simple videogame. Despite how much there is to describe of its many mechanics, I make few choices while playing it: What equipment does the Hero wear in battle, and what land cards do I place on the map. Everything else I would do in another RPG—walking the road, fighting monsters, resting in towns—is handled automatically. Despite this seemingly hands-off approach, it’s far from a passive experience. After every battle I am presented with quick and meaningful choices, then the Hero continues his loop and soon arrives at the next battle. Within seconds I’m making more choices, and I repeat. There are some frustrations. The Hero AI makes infuriating decisions in battle and building up the camp can become a frustrating grind. But I still find myself always ready for one more expedition and one more loop. There’s no other RPG quite like Loop Hero, and it’s worth playing for that reason alone.