Kena: Bridge of Spirits tells the story of Kena, a young woman on a pilgrimage to visit a sacred mountain shrine who finds her journey impeded by an angry spirit. Luckily Kena has the skills to deal with the situation, for she is a Spirit Guide, responsible for calming the spirits of the departed and ushering them into the afterlife. Pursuing the angry spirit, Kena comes across a ruined village at the mountain’s foot. The village is overgrown with ugly, red pustules that create entropic fields called Deadzones. To pacify the spirit that blocks her passage to the mountain shrine, Kena must purify the village of the Deadzones, help its former inhabitants pass on, and discover how its corruption and ruin is related to her pilgrimage’s destination.

If it weren’t for its startlingly current-gen graphics, Kena: Bridge of Spirits would feel indistinguishable from other 3D action/adventure platformers from the turn of the millennium. Progress through the ruined village is gated by both abilities and collectibles, which I need to discover and exploit in equal measures to overcome barriers that lead to Kena’s goal. The journey takes me through three areas in and around the village: climbing to a hunter’s lodge in a dense forest, to a magical forge where wood is molded like metal, and through the villagers’ abandoned homes where intimate frustrations still fester.

Of the many collectibles Kena gathers throughout the village, the first she encounters is The Rot, helpful bipedal critters covered in fine black hair with huge, expressive eyes. Their cute appearance and slapstick antics are the first indication I get about Kena: Bridge of Spirit’s spiritual philosophy, that death and decay are natural processes which lead to renewed life. This stands in stark contrast to other videogames and types of media, where beasts called The Rot would be malevolent and destructive creatures which must be stopped to create an unbalanced world of flourishing eternal life.

The Rot serve as helpful assistants to Kena on her quest. They empower her weapons and reveal enemy weakpoints. Out of combat, they appear in all manner of unlikely locations, sitting on walls and fence posts, peering out from bushes and behind trees, spectators to Kena’s efforts until she calls for their help. By pointing her staff, Kena can direct The Rot to carry heavy objects to another location, activate switches and levers, and accelerate the growth of gardens and farmland.

The Rot hide themselves throughout the village, waiting to be uncovered. Some are found by opening chests or defeating groups of enemies, while the more cunning have disguised themselves as a silvery light hidden on the surface of decorative stones or under heavy logs and rocks. My most demanding optional goal is discovering all one hundred of The Rot spread across the village and its outskirts.

Despite their prominence, The Rot feel more like a collectible extension of Kena’s abilities than a distinct mechanic. Presumably having too few Rot should render some obstacles impassable, like a heavy boulder or stubborn lever. Not once do I encounter a barrier I need more Rot to surpass. For a seemingly vital complication, The Rot prove so inconsequential I was able to summarize Kena: Bridge of Spirits’ premise in the first paragraph without mentioning them once.

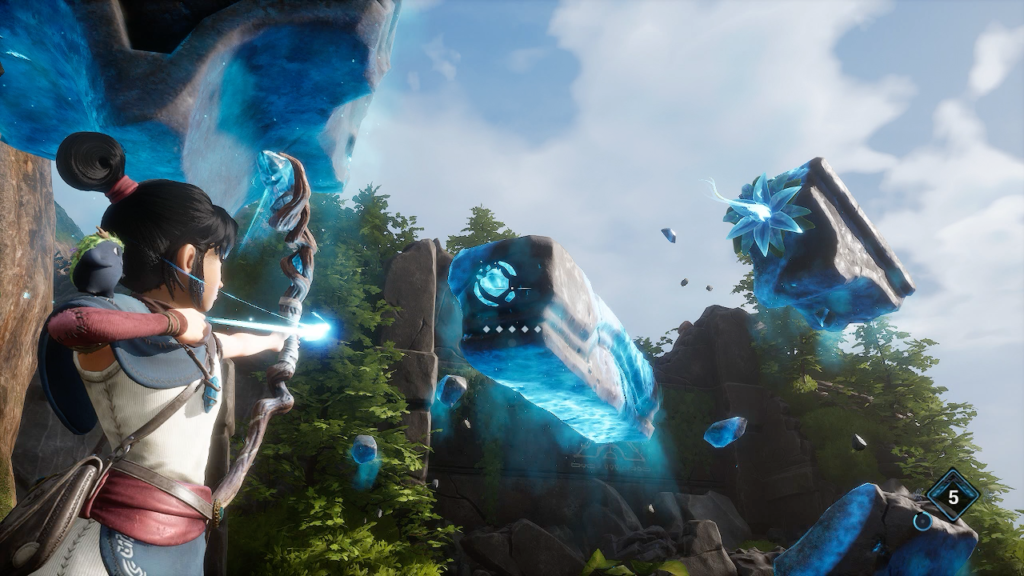

Other than The Rot, Kena has an efficient set of abilities she unlocks over her journey. In keeping with early-2000s throwback platformer feel, none of these abilities are groundbreaking. Kena learns to double jump, to turn her staff into a bow that fires arrows of spiritual energy, and to concentrate that same energy into an exploding ball.

Only this “bomb” has an unexpected mechanic. Its explosions work in the opposite direction, animating rubble instead of destroying it, briefly restoring collapsed structures to their original state. Some of the most skillful platforming sequences require me to clamber across these platforms before the animated spirit energy runs out and they collapse back to the ground.

Kena’s abilities are also used in combat. When she enters a Deadzone, she is attacked by monsters that rise from the blackened soil. These monsters are made of wood and stone and attack with ferocious anger, as though the very earth is rising against the Spirit Guide which has come to purify it.

Like the collectible-hunting activities and double-jump heavy platforming, Kena’s combat abilities would feel right at home in a 3D platformer from the PS2 or GameCube eras. She starts with a rudimentary combo attack using her staff, but I can embellish and empower her abilities by spending Karma, points earned for purifying sections of the village. I only wish giving Kena the power to charge her heavy staff swing, slow down time when firing spirit arrows, or counter attacks with a precisely-timed block was enough to help her survive.

I cannot overstate how difficult these combat scenarios are. Enemies, particularly the elite- and boss-level ones, are unexpectedly resilient; for all the mystical energy that Kena channels through her staff to solve puzzles and traverse the environment, in combat it really does feel like she is a child defending herself from violent monsters with a stick. Couple that with crevice-thin windows for blocking and countering enemy attacks, an uncooperative camera and target lock-on systems, huge damage output from the most dangerous monsters, and shockingly scarce resources to heal Kena mid-combat, and I find myself playing a videogame that is too hard to be enjoyable. I’m the critic who says Bloodborne is easy and I had to drop this vibrant, Pixar-esque videogame to its bottommost “Story” difficulty just to reach its ending credits.

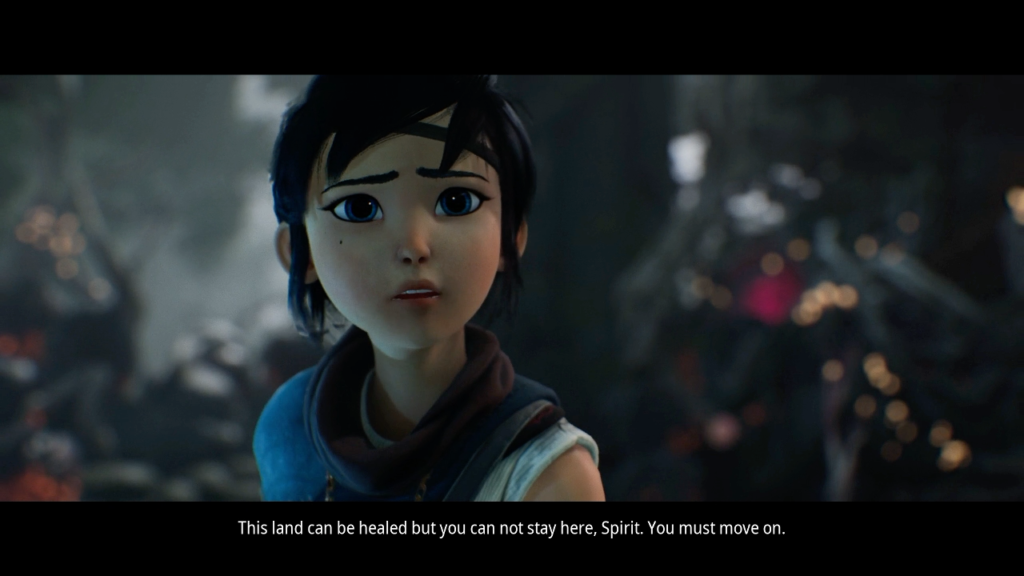

Kena: Bridge of Spirits’ visual resplendence is where it is most successful. Character models are wonderfully detailed and brought to life by subtle animated touches. The sadness and rage of the spirits Kena helps throughout the village are etched into their faces, communicating without words their helplessness and their confusion of how they got there. These elements exist when the videogame is in action, but it never looks better than when it’s running a cutscene. I eagerly await the theatrical black bars which tell me what I’m about to witness will be a visual feast.

Color is cleverly used to communicate my progress in the current area with a single glance. The red color that represents the village’s corruption is always countered by the Spirit Guide’s bright blue. When I see them at war, I know there is still another mystery, another spirit, or another Deadzone close by. When all I can see is green, the area is in balance between life and death, and I know I must guide Kena onward to continue her duties elsewhere.

Unfortunately even the visuals sometimes push Kena: Bridge of Spirits too far. In large areas there are framerate drops as the engine struggles to animate everything around the player character. Resolution and framerate tricks are sometimes glaringly visible, revealing the artificiality of the videogame in a way the animated cutscenes hide to great effect.

Kena: Bridge of Spirits isn’t a successful action-adventure videogame. Its adventure elements are average at best. The environment is dense with collectibles that empower Kena but the activities begin to repeat themselves almost immediately. The action is downright bad, not doing anything interesting and being controller-crushingly difficult while it’s not doing it.

It’s in visuals and themes where Kena: Bridge of Spirits stands out. The developers have a background in animation, and their talents shine through in this area. Seeing the village slowly transform from a corrupted ruin infested with pulsating red infection to a lonely green ghost town suffused with blue spiritual energy gives a real sense of Kena’s progress and growing skill as a Spirit Guide. The underlying message that death and change are good and natural is communicated subtly. But videogames are not a purely visual medium, and these strengths cannot help Kena: Bridge of Spirits compensate for its design shortcomings.