Death’s Gambit: Afterlife is a side-scrolling action-RPG about a soldier on a crusade to the heart of a cursed kingdom defended by an immortal army. It is also a significant reworking of the original Death’s Gambit videogame, which I did not play and will address no further in this review.

I play as Sorun, a young soldier charged with infiltrating the citadel Caer Siorai in the kingdom of Aldwynn to claim the secret of immortality rumored to be kept there. When his unit reaches the border they are immediately slaughtered by an invincible warrior. After his final breaths, Sorun is approached by Death and offered a contract: Find and destroy the source of immortality in Caer Siorai, and he will never truly die until his mission is complete. Resurrected as a quasi-immortal revenant, Sorun gains the power to overcome Aldwynn’s protectors and destroy the source of immortality—no matter how many deaths it might take him.

I typically push back against the tendency to label videogames as “souls-likes.” The influence that Dark Souls has on videogame design, and indie videogames in particular, is difficult to deny. Yet few wholly replicate the Dark Souls experience.

Usually when a videogame is referred to as a “Souls-like,” the referrer means the player character loses a resource and returns to a previous checkpoint when they die, whereupon they must fight back to their corpse to reclaim that resource. This is only an incidental part of what makes Dark Souls unique. To encapsulate an entire videogame down to a single mechanic and declare it a genre is to be carelessly reductive. It does a disservice to Dark Souls and to the videogame being compared to it.

It is with this argument in mind that I state with affirmed self-consciousness that Death’s Gambit: Afterlife is Dark Souls rendered as a side-scrolling, platforming, action roleplaying game. Short a polygonal world navigated in three dimensions and intrusive player vs. player mechanics, all the elements of that most infamous videogame are recreated here.

I begin Sorun’s adventure by choosing which class he will adventure as. I can make him a Soldier, a mighty stalwart who withstands heavy blows with his shield then retaliates with a swing of his massive longsword. Or an Assassin, a nimble fighter who dodges past his enemies’ attacks and responds with quick strikes from dual-wielded daggers. As a Wizard he attacks from a distance with heavy-hitting magic that requires multiple charges to reach its full effect. The Dark Souls spinoff Bloodborne inspires the Blood Knight, who reclaims lost hit points with fast and aggressive attacks.

Yet which class I choose at the start is not how I have to finish; by seeking out certain weapons and skills and investing Sorun’s levels up in the right places, a Soldier can wield the magic of a Wizard and a Blood Knight can gain the Assassin’s nimble strikes.

After choosing Sorun’s class, I strike out with him into Aldwynn. Almost immediately he is beset by the monsters that used to be Aldwynn’s populace, driven mad by interminable centuries of immortality. I can heal the damage Sorun takes in battle using a phoenix feather, an item with limited uses that can be replenished at a save point, but doing so also brings every killed non-boss monster in the world back to life.

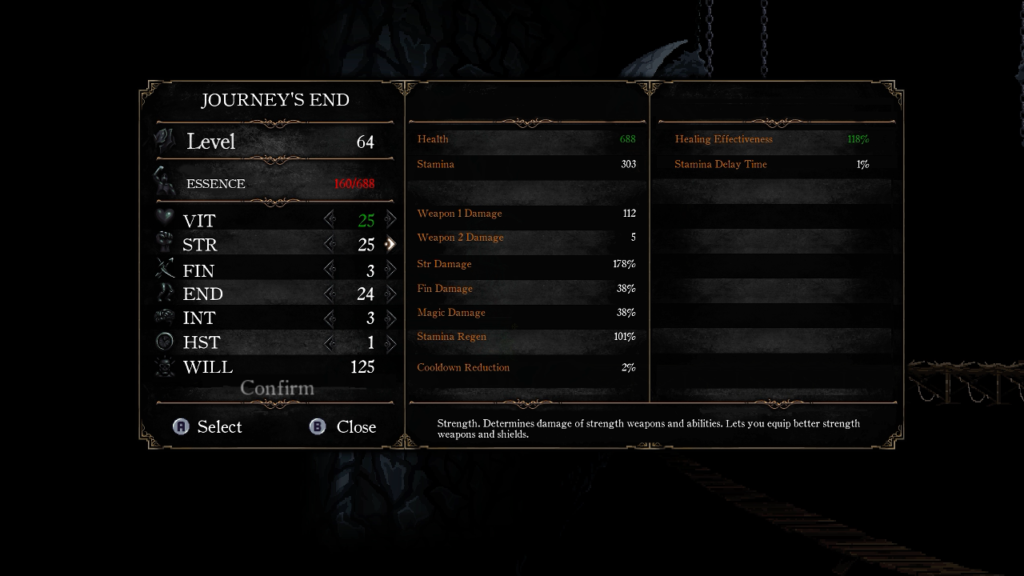

When monsters are defeated, Sorun absorbs a resource called Essence from their bodies. Essence can be spent at save points to buy steadily more expensive stat upgrades. Different weapons rely on different stats to boost their effectiveness, but no player character is complete without deep pools of health to absorb additional damage and stamina to fuel their blocks and attacks.

I have remarkable freedom in my exploration of Aldwynn. There are a few doors and barriers Sorun cannot pass until he finds a new key or ability, but my path to Caer Siorai is far from linear. In my explorations I introduce a sketchy NPC to the main hub area who slowly murders every other NPC, denying me access to their services and input unless I realize he is the culprit and put a stop to his spree. Useful information like this is rarely exposited to me, instead communicated through item descriptions whose relation to characters and settings must be puzzled out by inference and experimentation.

In short, if you’ve ever succeeded in a Dark Souls videogame, Death’s Gambit will offer you few challenges and fewer mysteries.

Yet it would be unfair to accuse Death’s Gambit of being an out-and-out clone or unlicensed remake of Dark Souls. It does make some choices which give it a personality apart from its inspiration.

The first and most notable difference is in how it tells a story. Death’s Gambit is happy to stop the action for a moment to allow two characters to have an actual conversation. Their exchanges reveal depth and motivation to characters who continue to exist and act within the world even when they’re not on screen. Even Sorun himself feels like a living person. His motivations are enriched by regular flashbacks to his childhood, showing his close relationship with his mother, who was also sent to her death trying to retrieve the secret to immortality. Instead of an empty shell, Sorun is a player character with a past that haunts him and a future that matters to him—and thusly, to me.

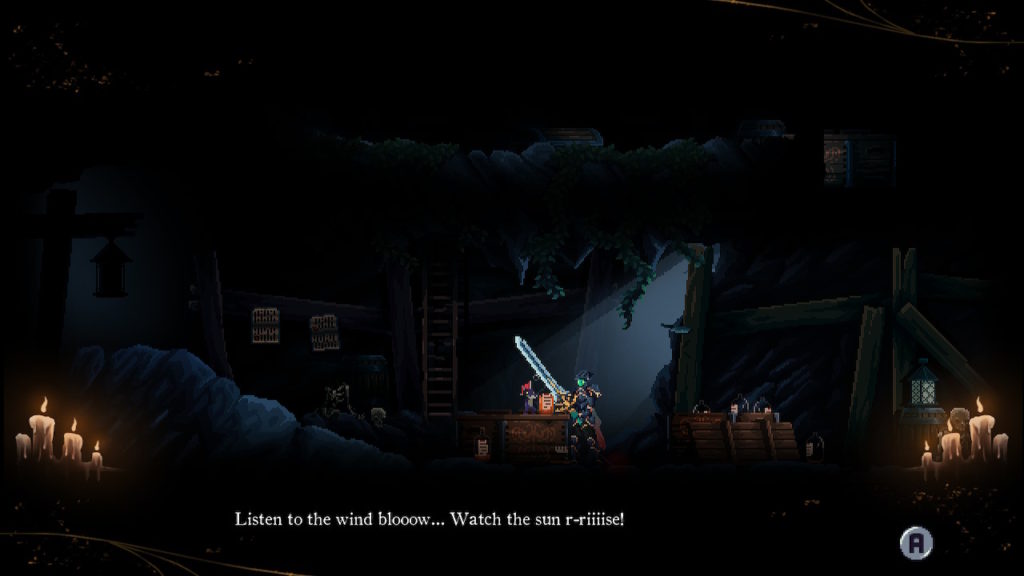

Death’s Gambit also knows how to pull itself from its dour malaise to tell a few jokes. When Sorun is first resurrected by Death, I can send him back home, earning an “ending” suitable for such cowardice. Soon after he meets a diminutive creature called a Lumberkin nursing a drink and slurring the lyrics to Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain.” Death goes for the most laughs. Normally an imposing and menacing figure, Sorun can stumble across him working as a meek and harried sous chef who is quite embarrassed to be discovered. Later, he is distracted from monitoring Sorun’s progress by a videogame. Not every joke lands, but it’s nice to see the mood lightened from constant gloom and gore.

Where Death’s Gambit feels most unlike Dark Souls is the Soul Energy that powers special attacks. Every class earns Soul Energy in a different way, and while I can use any ability with any class if I take the time to learn it, the way I earn Soul Energy is locked to the class I choose at the beginning. I played through the story as a Soldier, who earns Soul Energy by blocking attacks with his shield. The Soldier’s Soul Energy can be used on skills like Heroic Lunge, which deals a burst of damage and increases the damage all attacks deal for several seconds, and Winding Hew, a swift blow that applies a bleed effect to enemies, slowly draining additional hit points over time.

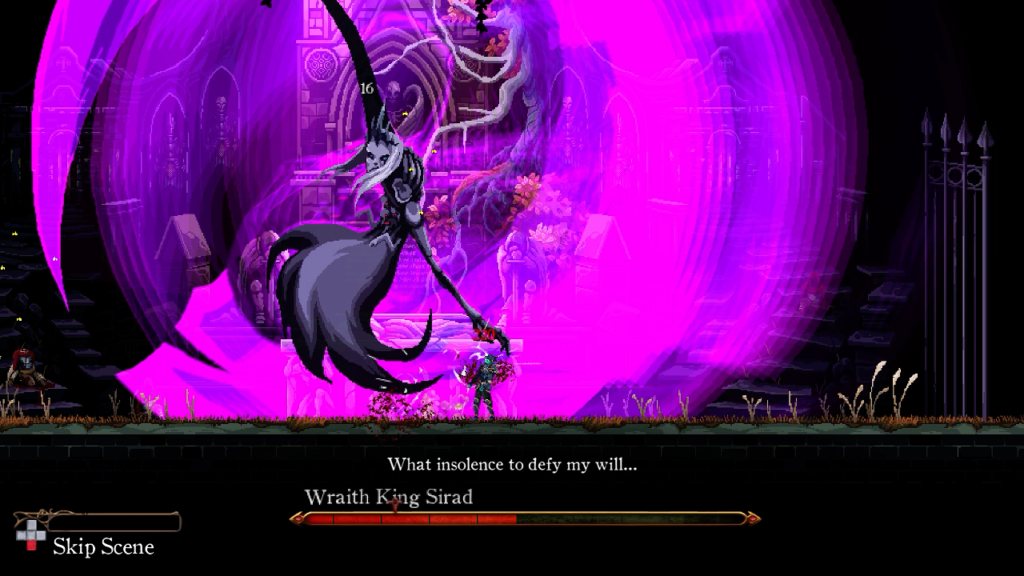

It’s with Death Gambit’s bosses where the design gets the most creative. Bysurge the Lightning Lurker alternates between red and blue auras, and I must change Sorun’s aura to the opposite color to deal more than scratch damage. The Forgotten Gaian is a near-invulnerable giant whose feet must be hacked at until it stumbles, bringing its weak points closer to Sorun’s reach. Tundra Lord Kaern is fought on a teetering platform which must be kept counter-balanced to stop the entire arena from tumbling into the abyss. There are as many bosses which can be beaten with tried-and-true tank-and-spank tactics, but I can never assume that my old standbys will work in the next encounter.

I can’t explicitly compare a videogame to Dark Souls without addressing the overemphasized difficulty topic. As with Dark Souls, the biggest difficulty barrier in Death’s Gambit is understanding the statistics that determine the player character’s effectiveness. It follows the same basic rules as its inspiration, but significantly simplified. Without giving away how everything functions, suffice to say I only put points into three of Sorun’s six stats and suffered no real problems facing the world’s challenges on even footing. If you’re a Dark Souls veteran, I predict you can guess which stats I chose.

The rest of the difficulty comes from reacting to the platforming and combat challenges. Sorun gains access to the full suite of platforming abilities as he defeats bosses; air dashing, double jumping, ground-pounding, all the boxes are checked off here. These abilities combined with the mild world difficulty, marked by few bottomless pits, spikes, and other instant-death traps, make Aldwynn into a friendly platforming environment for all skill levels.

Combat is where I feel the most actual difficulty. Some monsters are invulnerable until I block their attacks with precision timing or use a Soul Energy-powered skill against them. Others wield weapons so massive that I am not safe from their attacks even standing directly behind them. Bosses, naturally, put me through my paces the most, requiring me to learn their tactics and practice my strategies to overcome them as they grow progressively stronger and faster. Some of the later bosses are so quick that I struggle to turn and lift my shield as they attack from successive sides; Sorun’s response to my controls feel a little too sluggish to meet his foe’s speed.

Graphically, Death’s Gambit feels distinct, if unremarkable. Suitably dark colors abound and every important character gets a large, detailed profile picture to accompany their dialog to create a stronger sense of identity and personality. Actual character models are less impressive. Sorun’s yellow eyes are rendered as single yellow pixels on a green circle, making him look less like the living corpse his scarred profile picture shows and more like a bipedal frog shoved into a suit of unflattering armor. Animations are even less impressive. All of Sorun’s movements seem to only come from his joints. Maybe this is meant to suggest the onset of rigor mortis to his technically-dead body, but instead it looks like the bones in his spine, arms, and legs have been replaced by steel rods.

Death’s Gambit: Afterlife is a reverential indie homage to Dark Souls. Its most important elements—the abstruse stat-driven combat, the rich lore communicated through disparate puzzle pieces, the “git gud” boss battles and enemy encounters—are recreated faithfully. It steps away just enough through humor, storytelling, and special abilities to avoid outright plagiarism, but it’s still easiest to recommend it to existing Dark Souls fans. If you’ve never been successful in a Souls-like before then Death’s Gambit might be Souls-lite enough to ease you into things. It’s a fair experience, but will always exist in my mind as “that videogame that only made me think of Dark Souls.”