This may be the most pointless review I will ever write. My mandate on this website is to write a review of every indie videogame I finish. I have recently completed a two year run on a fresh farm in the Valley, and so I find myself sitting here committed to writing about one of the most oversaturated videogames of the past decade. Its release in 2016 revived a once-promising niche genre which had stagnated since its height in the early 2000s. The revival was so successful it created a cottage industry of imitators which have become eye-rolling punchlines in the indie videogames community. Every week there’s another “cozy farm sim” released or announced. Some of them are even good.

None of them are Stardew Valley.

The story begins with the player character working a soulless office job at the all-consuming Joja Corporation. The environment is oppressive. Managers in black suits peer down on the office floor from high windows. Each cubicle is equipped with a security camera pointed conspicuously at its occupant’s chair. Most cubicles don’t seem to have entrances, their walls joined with their neighbors in contiguous cells of endless corporate drudgery. It resembles less an office space than a prison.

The player character hides in their desk drawer a Get Out Of Jail Free card: An envelope, left to them by their late grandfather, whose final wish was for them to open it when they feel “crushed by the burden of modern life.” Finally unsealing it, inside they find a letter and the deed to a farm in Stardew Valley, “the perfect place to start your new life.” They quit their job on the spot and take a bus to their new home and their new life as a farmer.

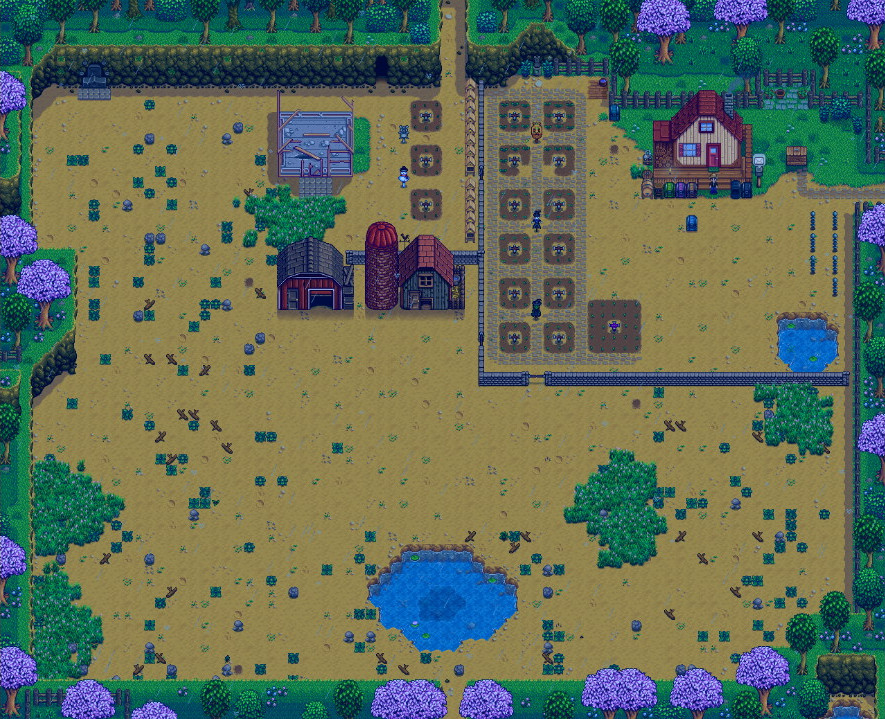

One of the most impactful choices I make for my neophyte farmer before they arrive in the Valley is what kind of farm they will live on. Knowing this visit to Stardew Valley will culminate in a written review, I opt for the default Standard farm so my experience will be as much like a first-time player’s as possible. The Standard farm is a long rectangle of dirt, a blank slate upon which I can impose almost any kind of agriculture and animal husbandry Stardew Valley is designed to support.

The Standard farm is the least restrictive of the available options. As I grind through two in-game years to reach the first nominal endstate, I come to regret this lack of restriction. I am bored with not having to compromise on any of my desires and compulsions. When creating something, even a farm layout in something as regimented as a videogame, restriction can be the manure that germinates a seed of creativity. I wish I had chosen one of the many other farms which have been added since Stardew Valley’s launch. Each offers some kind of restriction or constraint to work around, emphasizing playstyles different from the ordinary, flat Standard farm.

The Riverland farm floods most of the property with water, turning it into a patchwork of islands connected by rickety bridges. It leaves less room for growing crops and fostering farm animals, but makes it easier to fish, a vital source of funds before the farmer achieves a stable income. The Forest Farm overgrows most of the fertile soil with wild trees and bushes. It’s easier to harvest lumber and forage for wild produce on this property, but it takes a while to have a strong enough axe to cut every kind of tree and stump found there. The Hill-Top farm adds a lot of uneven terrain. Even crossing this farm is time-consuming, let alone cultivating it into a money-making business. The Beach farm is deceptively spacious, but the terrain restricts the use of advanced farming tools. It is essentially Stardew Valley’s hard mode.

Whichever farm type I choose, the farmer cannot do anything with the new property until they tend to its neglected fields. The long-abandoned farmlands are overgrown with grass, shrubs, trees, stumps, rocks, and boulders. Clearing them all out introduces me to the tool system.

The farmer begins with a pocket full of basic handheld farming tools: An axe to chop down trees and stumps, a pickaxe to smash rocks and boulders, a scythe to cut grass and shrubs, a hoe to till the land for seeds, and a watering can to water crops. Their tools aren’t strong enough to clear every stump and boulder in the entire field—the farmer will need to upgrade their axe and pickaxe using ore prized from the local mine before the field can be fully cleared—but on the first day they are able to clear enough of the rich, brown earth in front of the farmhouse’s doorstep to plant their first batch of crops.

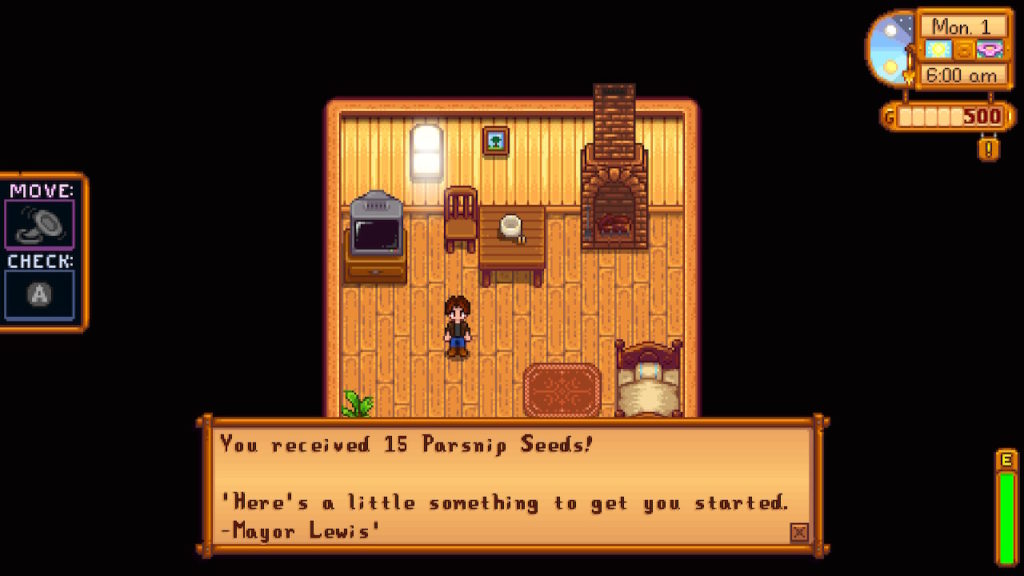

As a farm sim, growing crops is the most prominent and traditional way to make money in Stardew Valley. When my farmer awakens on their first day living on the farm, they discover that Mayor Lewis from nearby Pelican Town has left a bundle of parsnip seeds on their table. The money earned from growing these vegetables will be the basis for all other developments made to the farm.

Growing crops is a combination of effort and time. After clearing a space of fertile soil, the farmer tills it with their hoe, plants any seeds from their pockets, and waters them using their watering can. The watering can is spacious, able to hold forty “charges” of water before it needs to be refilled from one of the farm’s many water sources. Its size is a major improvement over the farm sims which predate Stardew Valley, whose default watering cans could often hold barely a dozen charges, resulting in lots of tedious back-and-forth between thirsty crops and water sources. Everything grows in compressed time, so the parsnips develop from seeds to mature vegetables in just four days with regular watering.

Time is the force that drives and limits the activities the farmer performs in Stardew Valley. They wake up each day at 6am and it is my goal to help them accomplish as much as they can before nighttime comes and they must retire to sleep. On the first day, watering all fifteen of the first batch of parsnips takes only about an hour of in-game time. I send the farmer to Pelican Town’s shop to spend the last of their savings on more seeds. Even after this trip and more time planting the new seeds, it’s still only a little after noon. The remainder of the day is spent clearing out the overgrown farmlands.

Stardew Valley’s other limiting force is the farmer’s stamina. Tending to crops takes only a modest chunk of their daily total stamina. Breaking stones and chopping stumps takes far more stamina, and the farmer is often exhausted long before nighttime falls while clearing the overgrown farm. If I keep pushing them past their stamina meter’s limit, they will pass out, waking up the next day with several statistical and financial penalties. After a few days’ work, most of the debris is cleared away and the farmer has a lot of time and stamina left to perform other tasks around the Valley.

I compliment Stardew Valley for its massive watering can. I cannot be as complimentary about its stamina system. While I feel its restrictions with a fresh farmer on a new farm with all its debris still to be cleared, once that few days’ work is done it takes purposeful effort to drain the farmer’s stamina to zero. The meter can be expanded by finding rare Stardrops, and the amount of stamina the farmer uses performing various tasks is reduced as they become more experienced at them. Before the farmer’s first year on the farm is even over I simply stop paying attention to the stamina meter. It becomes a non-factor that quickly. A system which can be ignored should be removed entirely.

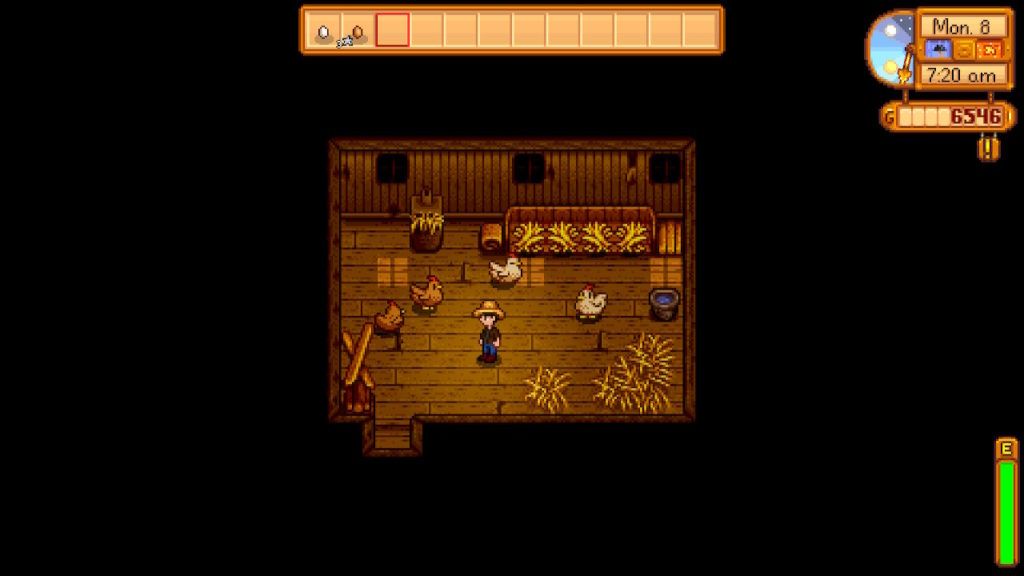

Once the farmlands are cleared of debris, Stardew Valley really opens up. With a little time and cash investment, the farmer can explore additional profit-making avenues on top of their crops. The most obvious choice is to build coops and barns to house chickens, cows, pigs, goats, and more unusual and fantastical animals. Eggs and milk don’t sell for as much as fruits and vegetables, but provide a steady daily income instead of irregular cash infusions whenever crops mature.

The farmer can also forage for mushrooms and herbs in the forest that surrounds their property. Upon acquiring a fishing rod, they can fish in the many rivers, ponds, and lakes around the Valley. They can explore the mines, a cave network with more than one hundred floors that hold not only valuable ore needed to upgrade tools, but also monsters that the local Adventurer’s Guild gives rewards for killing. All of these activities in some way feed back into drawing profit from the farm.

Ore pulled from the mines can be put to more practical use than selling it for money. Ore and other resources gathered from around the Valley can be used in a massive and robust crafting system to create both decorative and practical objects. The farmer can place decorative objects almost anywhere on the farm, creating elaborate paths and fences from stone and wood that truly make the property their own.

The practical objects are more impactful. Machines can turn eggs and milk into mayonnaise and cheese which sell for much more than their unprocessed forms. Different kinds of aging barrels can also be made to turn fruits and vegetables into preserves and spirits. Processed produce even has the same advantages and disadvantages as their unprocessed forms; mayonnaise and cheese offer steady daily income, while preserves and spirits take longer to produce but provide much greater one-time returns.

The most powerful tools the farmer learns to craft are sprinklers. These devices preclude spending the farmer’s time and stamina watering crops every day. With enough resources to build an arsenal of sprinklers, growing crops stops being a question of how many the farmer can handle watering in a day to how many sprinklers they can cram onto their limited property space.

At first, sprinklers feel like a godsend. The sheer quantity of crops they enable without taking any extra time to maintain them is incredible. As the farmer creates more and more of them, I begin to resent their existence. There’s a pleasant and rewarding feeling to tending to growing crops which sprinklers robs me of. Early in the second year I realize the most efficient way to make money from crops is also the least satisfactory way to grow them. I yearn for the Beach farm, whose sandy terrain does not support sprinklers at all. The farmer quits their office job for a simpler life. I wish for them to quit their highly automated and mechanized simpler life for the simplest one.

That is easier said than done because making a profit is the most important part of Stardew Valley. It is the primary metric the player and the farmer are evaluated upon at the end of the second in-game year. This doesn’t make sense. The story begins with a staunchly anti-capitalist statement as the player character abandons a nine-to-five office-bound hell to embrace a self-sustaining farm life. Then they are judged primarily on whether they make a million bucks in two years. It’s thematically discordant and only softened by how this evaluation during a nominal ending doesn’t even matter. Whatever the result, the farmer wakes up in Year 3 exactly as they were the day before, and Stardew Valley continues on into infinity.

Aside from the profit-focused farming and crafting systems, Stardew Valley’s other major component is its social simulation. Nearby Pelican Town is home to more than thirty unique non-player characters, each with their own personalities, passions, foibles, and pratfalls. Ingratiating the farmer into this community and advancing from an unknown newcomer to the savior of the local economy is the other, much smaller part of how the farmer’s first two years are evaluated.

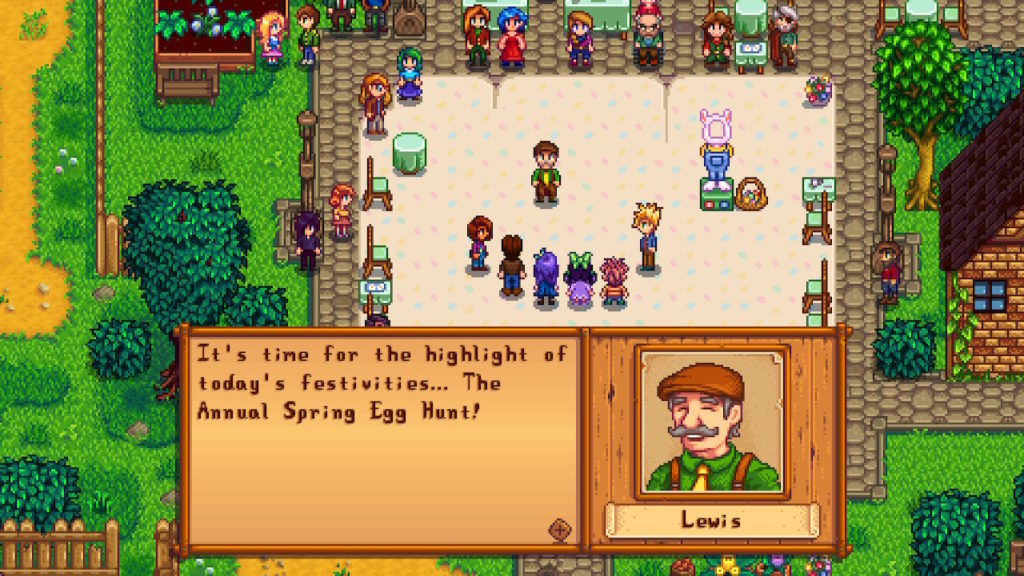

When the farmer arrives on their farm, they meet Lewis and Robin. Lewis is Pelican Town’s mayor, a role that sounds important but I soon realize is a mostly ceremonial position that calls on him to preside over local events and holiday celebrations. Robin has a more significant role in the farmer’s life through her job as a carpenter. She builds new structures for the farm and upgrades existing ones in exchange for huge stockpiles of lumber, stone, and money.

Another important figure is Pierre, the owner of the local store. The farmer visits Pierre’s frequently to buy more seeds for the farm. The shop also doubles as a kind of community center, containing a large common area where Pelican Town’s older women meet to exercise, and also a shrine to Yoba, the local deity. Pierre feuds with Morris, the manager of the local JojaMart chain. It’s possible to send the farmer’s business to JojaMart instead of Pierre’s, though this feels almost performatively cruel. Abandoning a Joja Corporation career, then becoming a JojaMart customer instead of supporting a local small business owner is another place where Stardew Valley feels out of step with its own message.

The most important citizens of Pelican Town are its twelve eligible bachelors and bachelorettes, six young men and women whom the farmer may meet, court, and eventually marry.

There’s a diverse and broad array of romanceable characters, each appearing to occupy an archetypical niche. Getting to know them better reveals their depths. Haley is the standout example. She is white, blonde, attractive, seemingly conceited, and concerned with clothing and her appearance. A quintessential mean girl. Getting to know her better reveals her interest in photography and the deep sentimentality she draws from fashion; her jewelry are mementos from her late great-grandmother, while her sister Emily is a budding seamstress. When I recognize these aspects to her personality I am less judgmental of her stereotypical surface.

Other potential partners include Alex, the local jock who lives with his grandparents; Abigail, Pierre’s daughter whose interest in the Valley’s more macabre and mystical elements worries her parents; Harvey, the town doctor with his mind in the clouds; and Leah, a sculptor who has also recently moved to the Valley to escape an unhappy city life. Like Haley, all of them have deeper nuances which reveal themselves as the farmer gets to know them better. Players should be aware that several of these characters explore difficult themes including alcoholism and suicidal ideation. Prepare yourself accordingly.

It seems almost quaint now, but the most significant part of the romanceable characters is their lack of heteronormative barriers. Farmers of either presenting gender (there is no non-binary option as of this writing) may pursue and wed any bachelor or bachelorette they choose. Some potential partners comment on their lack of homosexual feelings prior to meeting the farmer. Others don’t comment on it at all. The only thing that potentially raises an eyebrow is there are no partners who are homosexual by default. Since that would raise the possibility of a heterosexual farmer “curing” them into an opposite-sex relationship, that choice is probably for the best.

Making every partner potentially part of a homosexual relationship was a bold and original choice when Stardew Valley launched and the effect it had on the industry at large should not be overlooked or understated. Previous farm sims would have a patronizing “best friends” option for same-sex partnerships, if they had one at all. Post-Stardew Valley, they all do it. Even the most conservative series now include same-sex marriage options.

As much as I admire Stardew Valley’s progressive portrayal of sexuality and relationships, I do have to criticize it for how those relationships develop. It’s the same criticism that I always expound about developing relationships in social simulations.

Every character in Pelican Town has a relationship meter assigned to them portrayed as ten empty hearts. The farmer can fill these empty hearts by interacting with their owners. Small things like speaking with them will fill a heart by a tiny amount. To really get the relationship growing, the best way is to give gifts. Each character has specific items they love or hate which can be grown or found around the Valley. Most have a broad pool of things that everybody likes at least a small amount; filling the farmer’s pockets with flowers picked from around the Valley and presenting them to every character they encounter is an effective way to fill up meters without much effort.

Spontaneous flower giving is one thing. This system becomes creepy when the farmer takes a particular interest in one Pelican Town denizen and makes a point of memorizing their schedule and bombarding them with their favorite rare and expensive gifts. In real life, this is stalking behavior and is rightly seen as invasive and disturbing. In Stardew Valley and other similar social simulations, this is power leveling encouraged by designed systems.

Gift-giving social simulations reinforce a toxic idea of relationships where romantic feelings result from harassing someone with unasked-for attention until they relent. They take a serendipitous process built on mutual attraction and respect and distort it into an experience point grind. I understand that these are just videogames and I should not overreact to simplified concepts, but the implications are there and I will call these systems out every time they appear. I yearn for a social simulator that dares to subvert this common design trope.

Despite releasing into retail in 2016, Stardew Valley has continued to grow in the intervening seven years due to the efforts of ConcernedApe’s solo development team, Eric Barone—though I would be remiss not to acknowledge the financial and technical support he has received over the years from many sources.

Updates have turned the Valley into a more magical place, introducing a local Wizard, Witch, and a whole underworld of grotesque-yet-friendly monsters. New activities and holidays have been introduced to keep the local community alive and thriving all year round. More dungeons have been added and the farmer can now travel to desert and island environments once they have completely conquered everything there is to do in the confines of the Valley. Even as I write this, another major content addition is on the horizon. Stardew Valley’s potential seems limited only by the attention span of its developer.

I need not be restricted only to Barone’s design choices. Stardew Valley is available on seemingly every current platform, from consoles to handhelds to mobile phones. The best platform to play it on may be the PC due entirely to an ecosystem of community-created mods.

There is a mod to change nearly any part of Stardew Valley I desire. The most common are simple graphic packs which change the Valley or characters’ appearances in small or significant ways. Somewhat more uncommon are mods which tweak an aspect of design. Nearly everything I have criticized in this review, from the irrelevance of the stamina meter to the ennui caused by the sprinklers to the implications of the social simulation systems, has been addressed in some way by at least one mod. Rarest but most significant are the total conversions which overhaul Stardew Valley into what is practically a different videogame. Mods like Stardew Valley Expanded and Ridgeside Village are so massive they demand their own reviews.

The buy-in for Stardew Valley is small. It retails for $14.99 USD on most platforms and often goes on sale for half that. Its PC version offers potentially limitless expansion through mods, most of which are free. There’s an enticing argument that the PC release of Stardew Valley is not only the best farm sim ever made, but thanks to its modding community is potentially the only one I will ever need to buy. That’s bad news for its countless “cozy farm sim” imitators.

I have no explanation for the huge success of Stardew Valley. I am perplexed that I enjoy a videogame which features a steady loop of simulated farm activities I readily refer to as “chores.” Some people seem to really like it. Others are actively repelled by its very concept. A good friend of mine refuses to even try it because the thought of a constantly ticking clock stresses him out too much. Even if its accomplishments are unknowable, they speak for themselves. Stardew Valley is one of the most successful videogames in recent memory, as memetically influential as Dark Souls and perhaps even more insidious.

Though I am not without my criticisms of Stardew Valley, every inch of its reputation is deserved. It’s a colossal videogame, so large that even this review cannot describe everything within it, and I expect it will be a fixture in my videogaming habits for the rest of my life. Anyone who has felt even a passing interest in farm simulation and social simulation videogames owes it to themselves to play Stardew Valley. It remains the undisputed master.