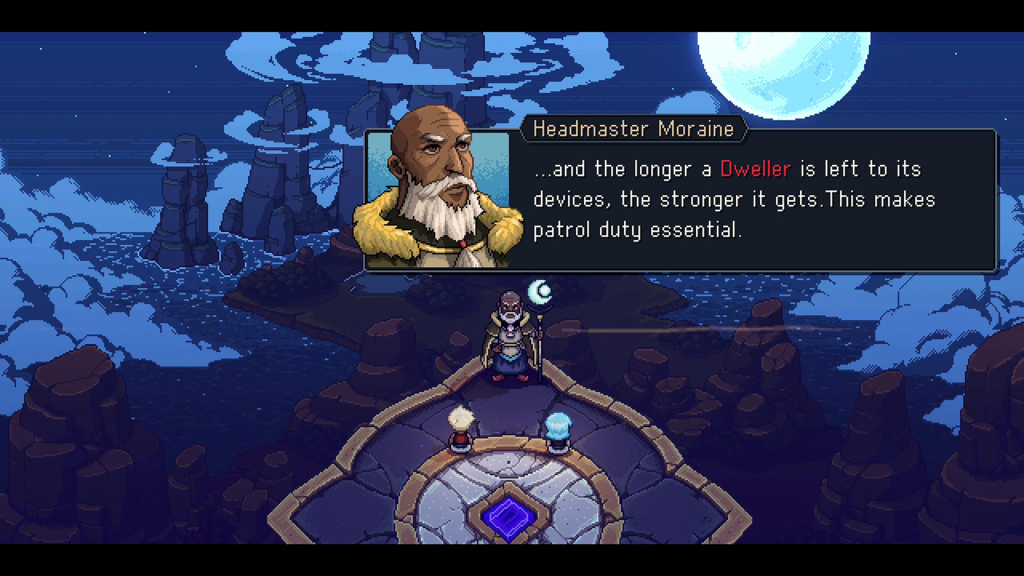

Sea of Stars is a retro RPG that combines the best elements of classic turn-based RPGs of the 1990s and early 2000s into a fantastic and cohesive package. I follow the stories of Valere and Zale, young Solstice Warriors who possess the magical powers of celestial bodies. Valere, born on the Winter Solstice, wields the power of the moon. Zale, born on the Summer Solstice, wields the power of the sun. After completing their solitary training at the Solstice Academy, they are sent out to defend the people of their world against the monsters who lurk in dark places.

Valere and Zale’s ultimate goal is to defeat the source of these monsters: The Dweller of Woe, the last in a line of parasites who sap the living of their lifeforce. If a Dweller accumulates enough power, it will grow into a world-destroying threat that will consume Valere and Zale’s home before moving on across the stars to other planets. Even before reaching this state, Dwellers are formidable creatures; the previous Dweller was only barely defeated, killing most of the world’s Solstice Warriors before its death, leaving the young and inexperienced Valere and Zale among the final five Solstice Warriors still alive to fight the last Dweller. Joined by a kind-hearted warrior chef, a mysterious assassin, and a powerful alchemist, Valere and Zale set out on a quest to save their world from the final Dweller and the shadows of strife and woe.

Valere and Zale are effective conduits for exploring the world represented in Sea of Stars. I can discern interesting details about Solstice Warriors by examining only their character designs. Their hair literally glows with magical power, Valere a pleasant blue as if from moonlight, and Zale a blinding gold as though from sunlight.

As RPG combatants, they are atypical. Though both possess impressive magical skill, it is the sword-wielding Zale who more comfortably fits the role of mage. He is even equipped with Healing Light, the party’s primary source of healing magic for much of their quest. Valere, by contrast, brandishes a staff, but feels much more effective as a physical fighter. These designs are typical of Sea of Stars’ use of RPG tropes: They appear familiar, but examining details more closely reveals knowing subversions and careful deconstructions of the expected.

I do have to accuse Valere and Zale of suffering from bland personalities. The pair are essentially interchangeable, singularly fixated on destroying the Dweller of Woe and lacking unique personal interests or conflicts to set them apart from the other heroes. I expect these flaws from player characters who must drive the plot forward without pushing too much against the player’s illusory boundaries of agency. As the primary protagonists of a 1990s-style RPG, it’s lucky they speak at all. The upside to their flat personalities is the supporting party members and non-player characters shine all the more, each possessing interesting depth and unexpected motivation.

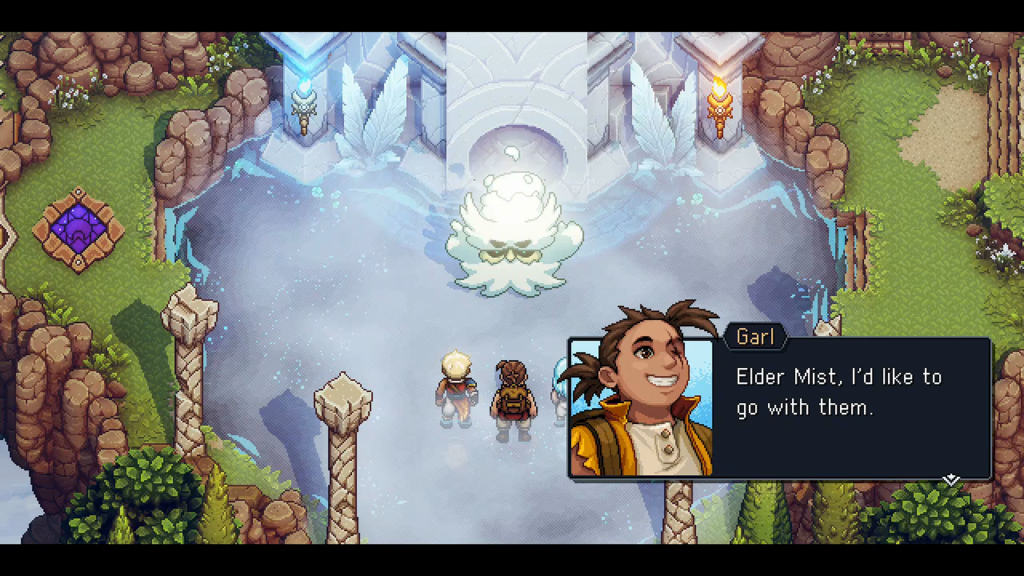

Valere and Zale are joined almost immediately on their quest by their childhood friend Garl. He’s the Samwise to Valere and Zale’s Frodo, brimming with good cheer, practical talents, and an anti-authoritative streak that in some ways make him the true hero of the story. A more unusual party member is Seraï, an enigmatic assassin. The plot has fun with her characterization, recognizing a twist involving her identity as so obvious it gets treated as a punchline. This makes it all the more effective when later twists about her identity are genuinely unexpected. Seraï is the party’s Aragorn, an experienced guide who knows more than she lets on and purposefully takes a backseat to the younger heroes. Rounding out the party is the alchemist Resh’an. He’s the party’s Gandalf, unfathomably powerful and frustratingly inscrutable in equal measure, desirous to help but bound by mystical rules the other heroes cannot comprehend.

Outside these playable party members is a large cast of supporting characters. Teaks is a traveling historian with a magical book that absorbs written history from the artifacts that witnessed it. She reads stories from this book at campfire checkpoints which fill in much of the world’s detailed backstory. Listening to them all is essential to understanding the plot’s more inexplicable events. To get around the largely ocean-bound world, Valere and Zale recruit a gang of pirates for the use of their ship. Led by Captain Klee’shaë (say it out loud), the gang provides much of Sea of Stars’ humor. Yolande Fortwal makes many knowing references to familiar storytelling tropes, while Jacko Valtraid and Keenathan engage in slapstick antics that disguise their kind-hearted competence.

Every character in Sea of Stars is memorable and gets at least one moment to shine. I don’t resent spending time with a single one of them.

I encounter most of these characters across a world created from several dozen isometric pixel art environments. Valere, Zale, and their party need to access distant and important locations on one of several islands to continue their quest and must traverse wildernesses teeming with wild animals and hungry monsters to reach them. Each area finds the heroes climbing up ladders and cliff faces, dropping down pits into caves, and swimming through ponds and rivers, navigating dense and winding labyrinths to find their way to an exit. These features combined with the isometric view make environments feel vertical and three dimensional despite their static and two dimensional appearance.

As Valere and Zale progress on their quest, they gain new tools and abilities which let them interact with the environment in new ways. A Mistral Bracelet lets them emit gusts of wind from their hands, pushing blocks and other heavy objects forward—yes, haters beware, Sea of Stars is loaded with block pushing puzzles. A Graplou is a length of rope attached to a blade the heroes can use to catapult themselves across gaps when it is attached to convenient anchor points.

Most impressively, Valere and Zale can use their celestial powers to change the time of day, advancing day and night through their cycles in seconds to activate magic stones sensitive to light from the sun and moon. These powers are visually impressive, shifting the lighting and shadows of each environment in condensed time, revealing the powerful technology that drives the seemingly simple visuals. Sea of Stars may look like a flat 16-bit videogame, but compelling the sun and moon through their cycles in seconds reveals its art is composed of innumerable beautiful dimensions.

No matter where the party travels, they are constantly confronted with engaging pseudo-platforming and interesting puzzles to keep me interested in what happens between Point A and Point B of the current plot beat.

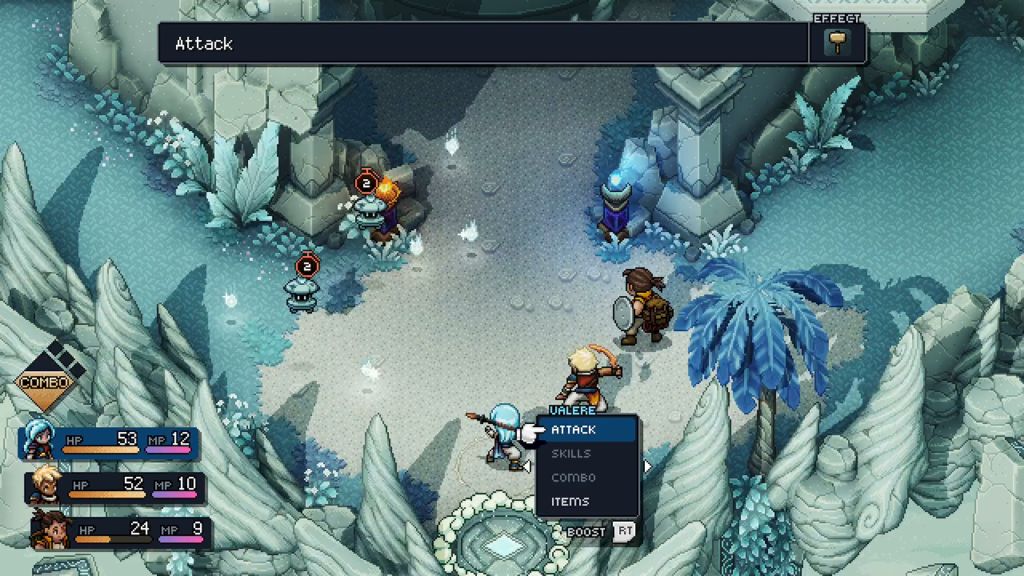

At Sea of Stars’ core are its combat systems. While the characters are memorable and the environments are beautifully dense, it is these systems which make a powerful argument for its RPG greatness. Combat begins when the party encounters monsters in prescripted locations in every environment—there are no random battles to be found here. It is built on a four-tiered system, building from the simplest and weakest attacks upwards to the most spectacular and powerful ones. The system is smartly constructed to keep all kinds of attacks relevant and useful. I never feel like I’m forced to waste a character’s turn on an action that doesn’t matter.

The foundation of the combat hierarchy are basic attacks. They are the most utilitarian attack in each character’s repertoire, dealing straight damage at no cost except the use of a combat turn. If I press the Confirm button with precise timing during a character’s basic attack, they will follow up with a second attack that deals additional damage. This mechanic governs almost every ability characters can use in combat; a “timed hit” will improve the damage of attacks, the health restored by healing magic, and the effectiveness of buffs and debuffs. It also works in reverse. Pressing the Confirm button with precise timing during an enemy attack reduces the damage it deals.

A secondary effect of basic attacks is Live Mana. Whenever any party member strikes an enemy with a basic attack, the blow produces tiny fragments of power called Live Mana which scatter upon the battlefield. Up to three Live Mana fragments may be absorbed by a party member to Boost the power of their next ability. When a basic attack is Boosted, it also adds that character’s innate magic to their attack. Monsters weak to moonlight will take additional damage from Valere, while monsters weak to sunlight will take more damage from Zale. Some monster varieties are practically invulnerable unless struck by their weakness, making strategic use of Live Mana essential for success.

The basic attacks’ last function is its most important: It restores the user’s mana points. Each party member’s individual mana meter powers the second tier of the combat system.

Skills represent each party member’s magical abilities in their purest form. Sea of Stars smartly limits the number of Skills each character learns at three. This prevents Skills from becoming obsolete as the characters ascend in power; Zale’s Healing Light is just as useful at the start of the plot as it is at the end. Skills persisting is especially helpful because squeezing out their maximum potential takes a certain amount of practice.

Like basic attacks, a Skill’s power can be increased by pressing the Confirm button with precise timing during the attack animation. Unlike basic attacks, this can be much more dramatic than an additional attack.

Zale’s Sunball sends a blazing orb of sunlight at a monster. If I hold down the Confirm button while it generates, it begins to swell with power. If I release the button just as it reaches its maximum size, it will deal additional damage to its target. Valere’s Moonerang involves even more technique. She flings a boomerang shaped like a crescent moon at a monster, which deals damage then rebounds back to her. If I press the Confirm button just before it reaches her, she will strike it and send it ricocheting to another monster, then back to Valere once more. The Moonerang keeps flying back and forth between monster and Valere, continuing with increasing speed until I miss the timing. With enough practice and concentration, I can keep the Moonerang rebounding for over twenty hits.

Sea of Stars wants me to use each party member’s Skills as much as possible. It takes a character two or three attacks to recover the mana they spend using one, but that still allows for multiple Skills to be used in every battle. I’m never left in any doubt of the heroes’ powers by a limited mana pool which strangles their ability to wield their magic.

I want to use as many Skills as I can because they build the meter which, when full, allows two or more party members to unleash the combat system’s third tier.

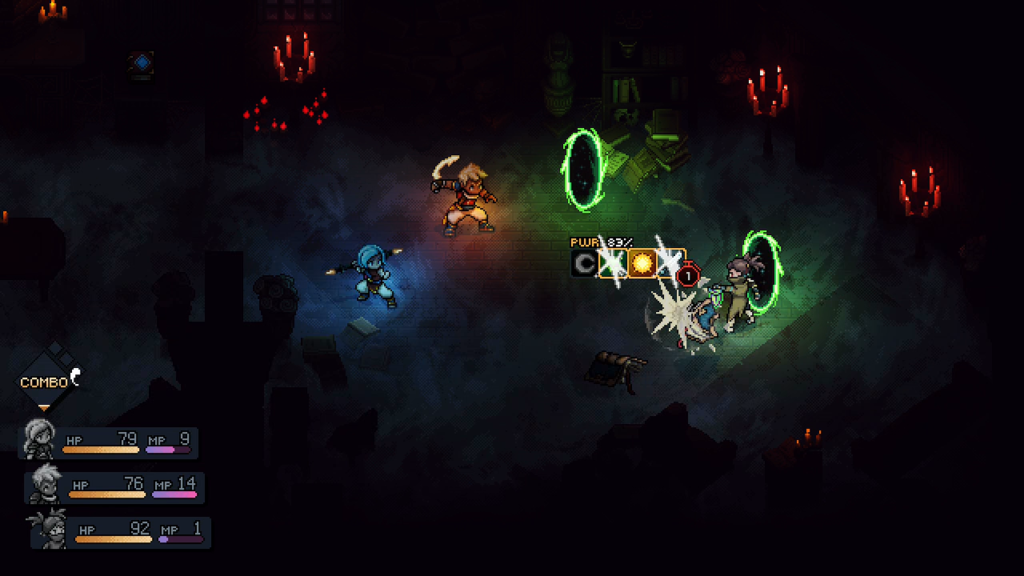

Combos combine the skills of two characters to create extra powerful effects. For the cost of only a full Combo meter, Valere and Zale can team up to cast Mending Light, magnifying Zale’s Healing Light through Valere’s moon magic to heal the entire party of almost all their wounds. Alternatively, Zale and Seraï can team up with X-Strike, striking a target with both of their blades simultaneously in a cross pattern, or Valere and Garl can team up, with Garl launching Valere onto an enemy’s head using his cooking pot lid.

I confess that I only see a fraction of all the Combos. It is all too tempting to save all my Combo points to cast Mending Light whenever possible. The tactic works so well to keep the party’s health topped out that it’s difficult to grumble too much about missing out on every fantastic Combo animation.

Using Combos charges yet another meter, the fourth and topmost tier of the combat system. When this meter fills, individual characters can cast their most awesome and powerful Ultimate attacks. Ultimates are Sea of Stars at its most visually inspired, combining scale and spectacle well beyond what 16-bit RPGs would have been capable of without completely forsaking its visual inspirations. This meter takes a long time to fill so I don’t get to use Ultimates often. When I do it’s a giddy treat.

Monsters do not stand idle while the party works their way through the combat system’s four tiers. Even the lowliest, weakest beastie in the bestiary can unleash powerful special attacks of their own.

Monsters’ special attacks are presaged by a countdown timer and a number of locks appearing above their head. The locks are fixed with icons representing the kind of attacks which can break them. Blunt-damage dealers like Valere and Garl can break locks with club icons on them, while Slicing-damage dealers like Zale and Seraï can break locks with sword icons. There are also locks accounting for every element of magic the party members bring to the field.

Every time a character takes a turn, the timer above the monster’s head ticks down. The more locks they break, the less damage the subsequent attack will deal. If every lock is broken, the attack is interrupted entirely.

This lock system, while injecting a lot of interesting strategy into Sea of Stars, is where I encounter much of my difficulty. There are many situations where it simply isn’t possible to break every lock no matter how many of the party’s resources are devoted to making it happen. It is common for multiple enemies to use a special skill at once, and even for a single enemy to keep using a special skill repeatedly. These factors can make battle difficulty feel frustratingly arbitrary. Most of the time I get the party through their combat encounters with a little thought and fortitude. Occasionally a monster group decides the party needs to die and there’s not a lot I can do to stop it, sending the party back to their last checkpoint.

To restore their hit points, mana points, and unconscious allies in combat, the heroes may use meals cooked at campfire checkpoints dotted throughout every environment. Ingredients are common, found growing almost everywhere and dropped by almost every vanquished enemy group, ensuring I can restock on used meals frequently. I have been trained by 90s RPGs to use items sparingly, which may be the source of the occasional difficulty spikes I encounter in combat. I use items rarely, as a last resort, but Sea of Stars’ cooking system doesn’t mandate this behavior. The party should eat well and often. There’s plenty of room for them to do so.

If I do find Sea of Stars’ default difficulty too challenging, then I can use Relics. These powerful items are found all around the world and may be toggled on and off for permanent effects. Most of them make the journey easier for the party. The Amulet of Storytelling doubles the party’s hit points and fully heals them after every fight. It is given to Valere and Zale as soon as they finish the combat tutorials, opening Sea of Stars to inexperienced players. Some Relics have only practical functions, like the Falcon-Eyed Parrot which reveals how many collectables are hidden in each area from the world map. The rarest relics actually make combat harder and are intended to be used on New Game Plus for experienced and challenge-minded players.

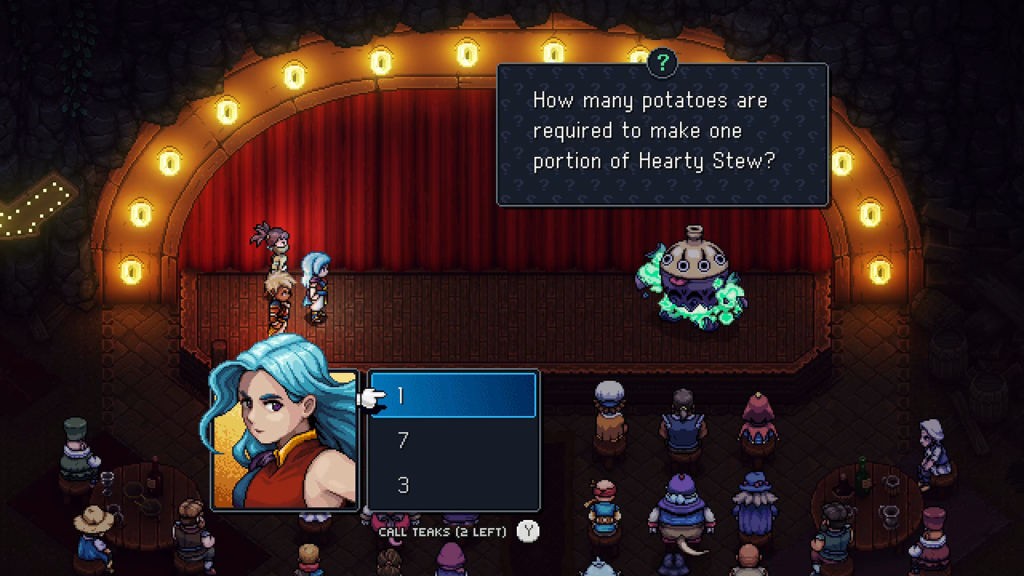

Aside from the main quest to kill the Dweller of Woe, Sea of Stars provides plenty of distractions for the heroes. Every environment is packed with optional puzzles and out-of-the-way treasure chests which reveal new combos, cooking recipes, historical artifacts, relics, and powerful equipment. A little girl in an underwater village gives rewards for finding sixty hidden rainbow conches. The heroes can participate in a quiz show for prizes beneath a haunted town. Optional bosses are available if I am curious enough to explore every nook and cranny around the world.

In every inn there is a competitive tabletop game played with clockwork figurines called Wheels. At first Wheels seems to provide the most strategic depth of all the side activities, until I discover every opponent can be easily defeated by pumping all possible resources into the Mage figurine every turn. This includes the final Wheels champion, the inventor of the game who presumably should be aware of this flaw in their game design.

The central conflict occupies most of my time with Sea of Stars, but there’s plenty to keep me busy if I want to spend a little extra time in its world.

These extra activities exist for more purpose than to pad out the runtime or satisfy hedonistic completionists. The default ending concludes on an unsatisfactory note. In order to face the true final boss and bring many of the plot threads to a more satisfying emotional conclusion, most of these optional activities must be completed first. Thankfully, when I discover this, I am annoyed just enough by the regular ending and equally enticed by unfinished activities to seek them out. Rather than burdening Sea of Stars with capital-C “Content,” these nominally-optional events and secret second ending are strong enough to feel enriching beyond the satisfactory core experience.

I believe fully appreciating Sea of Stars will depend on the player’s background in the kinds of classic videogames it builds itself upon. Readers could shout out to me almost any of their favorite turn-based RPGs from around the turn of the millennium and I could nod and say “yes, at least a little bit.”

Sea of Stars’ primary and most obvious inspiration is seminal 16-bit RPG Chrono Trigger. It borrows many of its visuals and themes and even echoes several set pieces in ways which would be obnoxious if they weren’t so reverently reimagined. I feel the presence of Golden Sun and Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga as well. The Solstice Warriors use their tools and powers to solve environmental puzzles throughout the world, as in Golden Sun, and perform timing-based activities to enhance their combat abilities like in Mario & Luigi. Thinking about all three of these videogames sends a nostalgic tremor through my bones and Sea of Stars keeps me vibrating pleasantly for over thirty hours.

Another videogame worth mentioning is The Messenger. Made by the same developer as Sea of Stars, it is a markedly different experience, being a side-scrolling platformer with few roleplaying elements and not a moment spent taking combat turns. They don’t even share a sense of humor. The Messenger viciously parodies videogame tropes with a cast full of fourth-wall-breaking characters. Sea of Stars, while not without some levity, takes its setting and characters seriously. About the only relationship the two share are their retro philosophies, using current technology and ideas to create new experiences that feel like old ones.

Despite these dissimilarities, Sea of Stars and The Messenger do share a setting displaced by thousands of years of history. The further I progress in Sea of Stars’ plot the more I recognize these connections. Some are obvious, like recurring characters and artifacts. Others are subtler, like an entire side-scrolling level from The Messenger reimagined as one of Sea of Stars’ dense isometric playgrounds.

I fear that listing all of these inspirations and predecessors here may feel like assigning homework. Please view it more as extra credit. Sea of Stars is a fantastic videogame on its own merits. I believe I would enjoy it even if I was totally ignorant of classic RPGs and missed 2018’s The Messenger. Backgrounding myself in these videogames enhances my appreciation of where Sea of Stars came from and where it tries to go. It takes a four star experience and makes it a five.

Sea of Stars is a new standout in the marketplace of indie RPGs. If I can offer any substantial criticism, it would be that it takes too long to get going, indulging in multiple lengthy flashbacks which interrupt the initial action and make the start of Valere and Zale’s world-saving adventure feel lackadaisical and distracted. Once all the actors are on the stage and their plots are in motion, its pace improves and the flow of events becomes much more unpredictable. If you think you know what Sea of Stars is about to do next, no you don’t. From its beautiful graphics to its inspired four-tiered combat system to its wonderful characters, Sea of Stars is best in class. It’s a must-play for any fan of classic and retro RPGs.