I like to play Cards Against Humanity with my nieces. It’s not a good game. It encourages a player to be as crass and vulgar as possible, or at least as much as the other players are willing to tolerate; it’s as much a social game as a card matching one, challenging its players to know not only which of their cards best matches the one that has just been read aloud, but also which of their cards suits the specific person who just read it. My nieces enjoy it because it gives them license to say words they would otherwise not be allowed to say. I enjoy playing it with them because it’s fun to make them laugh. It also creates occasional educational moments, like explaining classic Star Trek episodes, music that was popular when musicians still played guitars, and the Three-Fifths Compromise.

When we play Cards Against Humanity, I cannot stop myself from carefully sorting my cards. The cards in my hand must be organized by topic or category, no matter how arcane. The cards I’ve won are laid neatly in a row on the table, aligned along an invisible line in front of me, centered, and in the order I won them from left to right. I can sense the rest of the family watching me fuss too much with my cards, but nobody says anything. I don’t slow the game down, and it would feel wrong if they were placed in any other way.

A Little to the Left is a puzzle videogame about this compulsive need to arrange mundane objects in logical and pleasing patterns.

A typical puzzle consists of a pile of everyday items on a plain, pastel backdrop. The objects all have drab colors and fuzzy outlines, as though they have been cut out from construction paper and then scattered across the playing field. To solve the puzzle, I must scrutinize the objects, determine what they share in common, and arrange them in a way that brings order to the chaos.

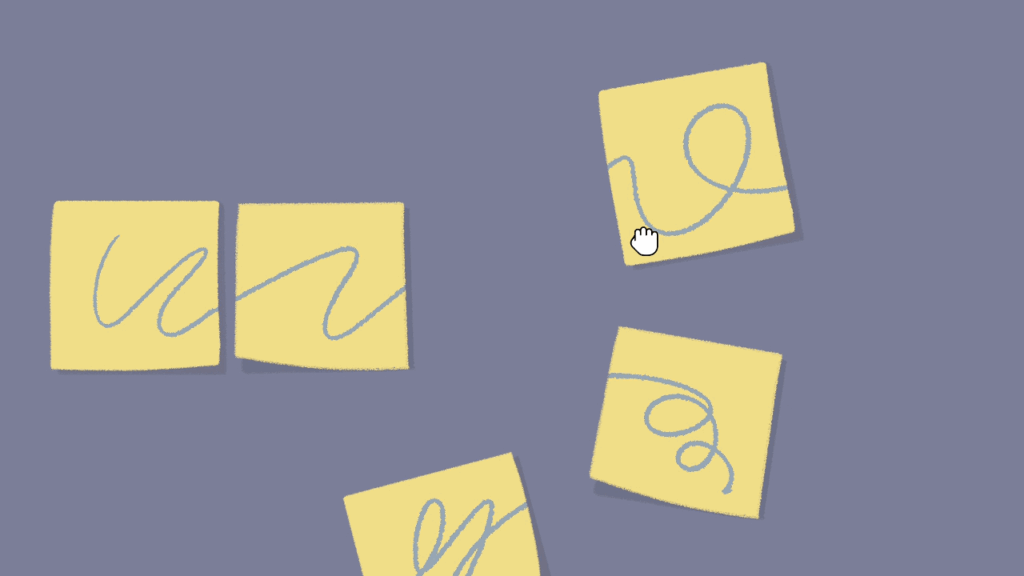

The most basic puzzles may be solved in seconds. Colored pencils are matched to the colored marks scratched onto the playing field. Sticky notes scribbled with a blue marker are lined up so the looping fragments form into a single, uninterrupted line. Random papers are stacked from largest to smallest, each successive one placed at the exact center of the one beneath it.

I can tell when I’m on the right track because a puzzle piece used in the right way will snap into place with a pleasing jump. I sometimes wish these snap points were visible on the playing field, though I understand that keeping them invisible keeps solutions from becoming too trivial. When I’m stuck, the temptation to take a puzzle piece and start randomly dropping it all over the playing field with the hope it will snap into place is already great—and sometimes it even gets results.

The earliest puzzles stretch the definition. The first tasks I am presented with are to straighten picture frames and move cat toys into a basket. These are more like impulses to tidy up a mess than a problem with an observable solution. Puzzles grow in complexity as I progress through their number and the quantity of involved pieces is raised. There’s a noticeable transition where I go from stacking NES cartridges into an orderly column to deducing a pattern in the stamps applied to the corners of envelopes. It’s a big step where puzzles evolve from compulsive tidiness activities to designed problems whose solutions must be found with thought and care.

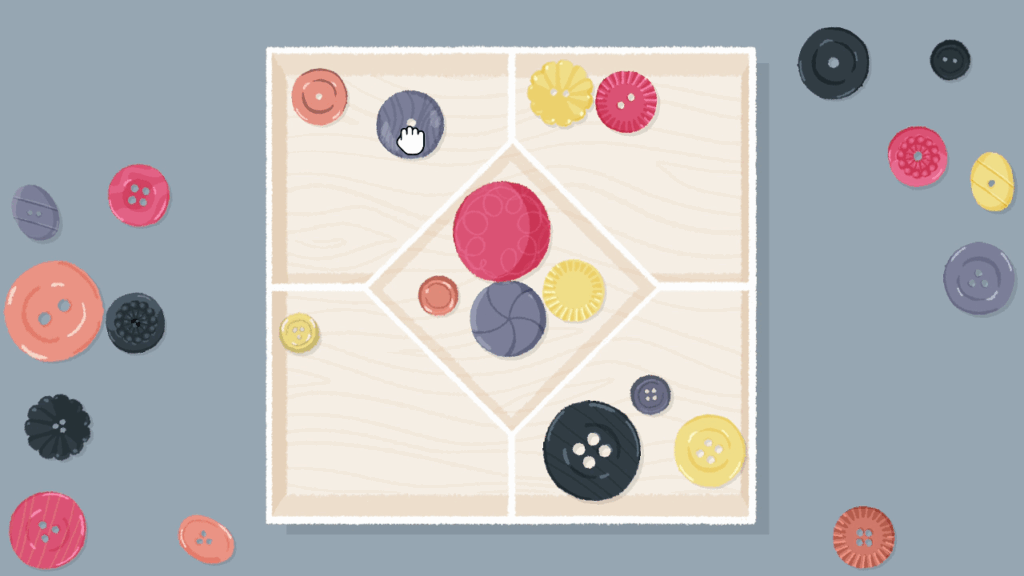

A Little to the Left ascends from interesting to inspired when its puzzles have more than one solution. As puzzle pieces begin introducing more components, the number of valid ways to organize them also increases. The earliest examples are correspondingly the simplest; sorting books on a shelf by their height is obvious, but it takes more observation and a willingness to look beyond their most immediate relationship to realize they may also be sorted by width. It takes a great effort of unorthodox thought to find alternate ways to sort pantry jars, varieties of spaghetti noodles, and a tray of seemingly random buttons. Some of the most elaborate puzzles have as many as three distinct solutions hidden in their disparate pieces.

The most complex puzzles meet at a precarious point between designed conundrum, cleaning activity, and abstract art project. It’s clear what I’m meant to do when I see a collected volume of books with a spiraling gold ribbon embossed along their spines. It’s less clear what’s expected from a box of dried leaves and twigs. I have to carefully examine every item, noting their shapes and colors, and come up with something that is aesthetically pleasing instead of simply organizing them by size or shape. The number of solutions to these puzzles is as impressive as the flexibility I am afforded in arriving at them. The downside is that while at first these puzzles are confounding, once I grasp what they expect from me, subsequent open-ended puzzles are as easy as straightening crooked picture frames.

As impressed as I am by puzzles with multiple or open-ended solutions, my favorites give me a haphazard pile of objects and a tray into which I am expected to make them all fit. These sorts of puzzles concern themselves more with finding which compartments an object fits snugly into than the relationship with their neighbors; they take more time than thought. A few still add some mini-puzzles as a wrinkle. It’s not enough to put all the batteries in a compartment into which they inexplicably fit perfectly, the batteries must also be arranged so their decorations form a pleasing pattern. I could not possibly be given enough of these junk drawer puzzles to be satisfied.

If I do get stuck on a puzzle, A Little to the Left provides a hint system. When I ask for a hint, I am shown an image of a solution to the puzzle. It’s deliberately limited. Only the most obvious solution is diagrammed, so if a puzzle has multiple solutions, I am on my own to find the trickier ones.

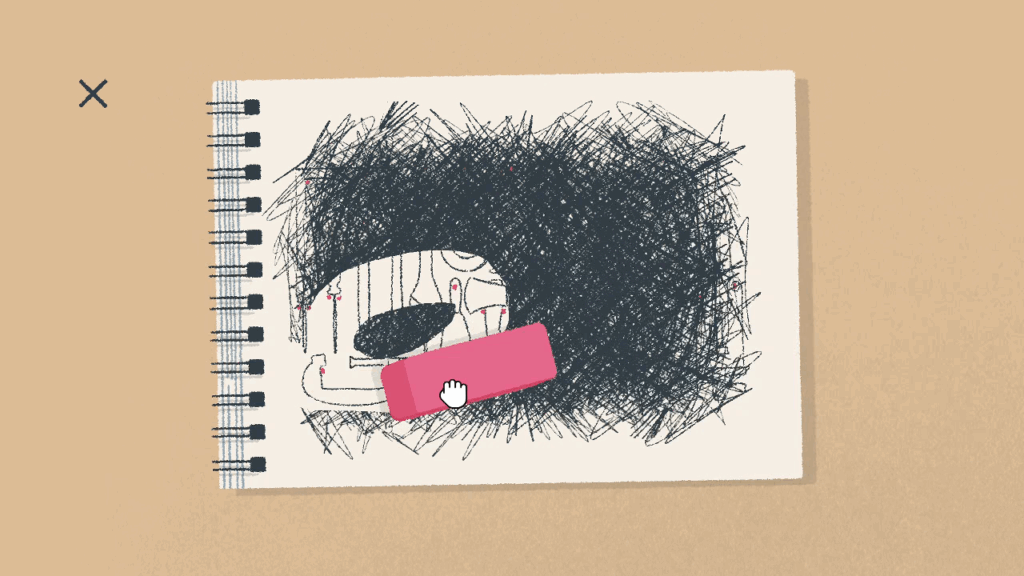

A clever twist to the hint system is the image is obscured beneath dense pencil scribbles when I first open it. I can reveal the hint by using the cursor to drag an eraser across the scribbles. This has an interesting effect on the hint’s value. If I only want a small hint, I can erase a small portion of the diagram. If that isn’t enough, I can reveal a bit more, and then a bit more, until I have revealed the entire hint if I’m just not getting it. For most of the puzzles I use a hint on, at this point the solution is practically shown to me. This keeps me moving forward if I become stumped by a particularly esoteric pile of objects.

A Little to the Left’s core content includes 80 puzzles with 108 total puzzle solutions. It takes me about five hours to work through them all. This doesn’t have to be the end of my puzzle journey. The main menu includes an Archive of a couple dozen special puzzles focused on specific holidays. There is also the Daily Tidy, a puzzle that rotates every day to keep me revisiting the game over weeks and months. Completing Daily Tidies rewards me with badges, and I must complete more than one hundred total to earn them all. Disappointingly, all the Daily Tidies I complete are recycled from the core puzzle set, though there may be some original puzzles hidden in its depths I haven’t encountered yet.

If I want to really challenge my compulsive, sorting-adjacent, puzzle solving skills, I can attempt the Seeing Stars and Cupboards & Drawers DLC packs. Each adds a few dozen more puzzles. These DLC puzzles are some of the most complicated currently available, including junk drawer puzzles where objects can be manipulated to change their size and shape. Some puzzles up the complexity to have as many as four valid solutions. Though the total number of puzzles might be fewer, their greater difficulty makes these packs take even more time to get through than the core set.

The way A Little to the Left tickles my compulsive tendencies is tremendously appealing. The part of me that enjoys seeking out the common relationship between uncommon objects, of bringing a semblance of logic to an illogical tangle, is overjoyed by this videogame’s simple conceit. Only the necessary limit on the total number of puzzles disappoints me. I wish this could keep drip-feeding me sorting puzzles forever. I will sort your junk drawers until the end of time.