Death’s Door is an exploration-heavy action romp through a secret land where wretched creatures have found a way to hide from their own mortality. I play as the Crow, an enigmatic agent of a morbid bureaucracy called the Reaping Commission. The Crow forcefully takes souls from living creatures and returns them to the Commission, where they are used to power the operation in a futile and macabre loop.

In my first mission as the Crow, I am charged with capturing a large soul from an especially dangerous monster. The mission goes well, but just as I am about to claim the prize, a Grey Crow appears behind the player character and knocks them out, absconding with the prize through a portal. I pursue the Grey Crow, tracking them to a cliffside in a crumbling graveyard.

There I learn the Grey Crow was once an agent much like the player character. The Soul they were charged with capturing has entered Death’s Door, a towering passageway floating in the air above the cliffside. The Grey Crow believes Death’s Door may open if more large souls are fed into it, allowing him to finish his mission. This is urgent, as a Reaping Commission agent’s mortality is reactivated until their mission is completed. With the Crow’s fate now tied with the Grey Crow’s, I agree to find more large souls in the hopes they will open Death’s Door, allow us to complete our missions, and reclaim our immortality. Finding these souls will take me to three mysterious lands untouched by death—at least until the Crow comes to visit.

While playing Death’s Door, my time is divided between exploration and combat. Environments are designed as labyrinths with winding, circuitous paths where I pass many sealed gates. Only by solving environmental puzzles or enduring combat gauntlets can I find the switches that open these gates, creating more direct routes through the area I can take on my next visit.

I view the world from an isometric perspective, looking down on the three-dimensional environment from a fixed angle. By guiding the Crow behind certain obstacles, the camera may swing around to reveal a previously-invisible area where upgrades may be hidden. Other upgrades are locked behind combat trials or obstacles I will not have the tools to overcome when I first encounter them.

Upgrades are familiar. Crystal fragments increase the Crow’s hit points or magic points by one when four of a matching color are collected. More prominent are soul orbs, a swirling energy mass that grants the Crow hundreds of souls which would take many hours to grind from standard enemies. Accumulated souls may be carried back to the Reaping Commission to increase the Crow’s attack power and speed.

These upgrades to the Crow’s vitality and strength are valuable because the denizens lurking in the undying lands fight with precision and ferocity. All enemies only deal a single point of damage when they strike the Crow, but this is small comfort when they only have four hit points at the outset. I must carefully dodge-roll away from every telegraphed attack and counterattack during an enemy’s brief windows of vulnerability. I can also attack from a distance using four different spells, though I must use the Crow’s melee weapons to recover spent magic points. This system smartly prevents me from getting easy kills using only the Crow’s ranged attacks.

Patching up after a few too many mistakes in battle isn’t as easy as picking up some dropped recovery hearts. Only certain life-giving plants will restore the Crow’s health. I can grow these plants in planters dotted around the world using seeds hidden around corners and inside innocuous containers. The more thoroughly I explore an environment, the more seeds I will have to grow the life-giving plants. These plants are permanent once I plant them, but they wither upon use. I can only restore them by dying or returning to the Reaping Commission—which also causes all of the enemies I have killed to respawn as well.

Most of what I have described are familiar design tropes, even cliché, so it’s refreshing to see so much original thinking put into the life recovery mechanics. Death’s Door rewards thorough exploration with more opportunities to heal, and punishes rushed or sloppy exploration with fewer opportunities.

This one single system does little to ease my frustration with how rote the rest of Death’s Door feels. The Crow begins with a weak Bow and Arrow spell which can be used to activate switches. Later, they learn Fire, which burns plants, and Bomb, which can blow open cracked walls. The final spell the Crow learns even lets me pull them across gaps to ankh-shaped targets. It’s called Hookshot. The brazenness with which these tools are pilfered from The Legend of Zelda and the lack of imagination with which they are recontextualized to Death’s Door is exasperating.

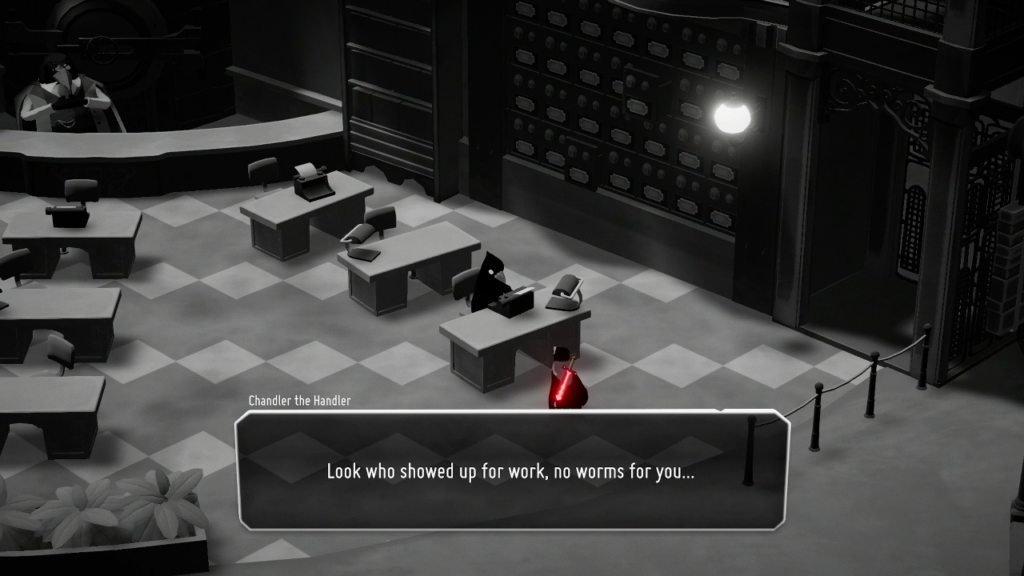

This is to say nothing of the Grey Crow, a pushy NPC who stands around the hub doing nothing while sending the player character off to kill things and claim their giant souls. It smacks so much of Dark Souls II my eyes are doing somersaults in their sockets.

Usually my frustration with a videogame’s systems and concepts feeling too similar to others influencing the zeitgeist is mitigated by interesting graphic design or writing. Characters, themes, and setting can elevate a videogame beyond an unimaginative collection of design tropes. Unfortunately Death’s Door doesn’t even have that going for it.

Death’s Door does begin with promise. The Crow arrives by flying bus to the Reaping Commission Headquarters, an office building resting on a shattered island in a foggy void. The setting is monochromatic, the greys and blacks on every surface only disrupted by the red highlight decorating the sword strapped to the Crow’s back. On my way into the office, I see an empty restaurant advertised by a neon sign that’s both a ramen bowl and a skull with its brain exposed. When I reach the Commission and meet the other crows, they are not clones of the player character but come in varying sizes and shapes that lends each a unique identity. It’s a brief, but memorable introduction to the organization around which much of the conflict revolves.

Then I’m kicked out into the world proper and I am dismayed to find it awash in a muddy splatter of desaturated greens and browns. The memorably stylized Commission is overwhelmed by a living world that looks like a parody of the “Real is Brown” aesthetic that dominated videogame art design of the mid-00s—only Death’s Door plays it deathly serious.

The story isn’t much better. It occasionally indulges in brief tangents about the nature of the Soul, the hardship of free will, and the necessity of death and aging. The script is far too brief to elevate these heady and well-trod philosophical concepts above eye-rolling pablum. The holders of the three large souls I hunt down to open Death’s Door have hints of histories and personalities, but if I’m supposed to feel some regret or hesitation at killing them to complete my mission, I do not. There is a twist villain who is so obviously villainous that I’m not sure it even qualifies as a twist. At every turn, Death’s Door fails to impress me.

When I say Death’s Door fails to impress me, I do not mean I did not enjoy it. It is a well-made videogame. Its particular problem is I enjoyed playing it already in the dozens of other configurations it has taken over decades. Mechanically, everything works as it should with an operational competence other videogames should aspire to. Artistically, it’s devoid of all but the barest hints of originality, overwhelming my experience with ennui. Death’s Door is a videogame all about taking souls from others, which is exactly how it got its own—from other, better videogames.