Airoheart is a retro top-down action and adventure videogame about a young hero who searches a fantasy world for fragments to a magical stone that imprisons an evil sorcerer. I play as the titular Airoheart, a young man descended from both the elf-like Elmer and the human-like Breton. This makes him an outcast in Elmer lands, where Breton are treated with scorn and suspicion. On an errand in town one day, Airoheart meets a band of vigilante Elmer tracking a Breton scouting party. Wishing to prove himself, he joins the group and tracks the Bretons to a nearby cave. What he discovers there launches him on a quest that will determine the fates of both the Elmer and the Breton.

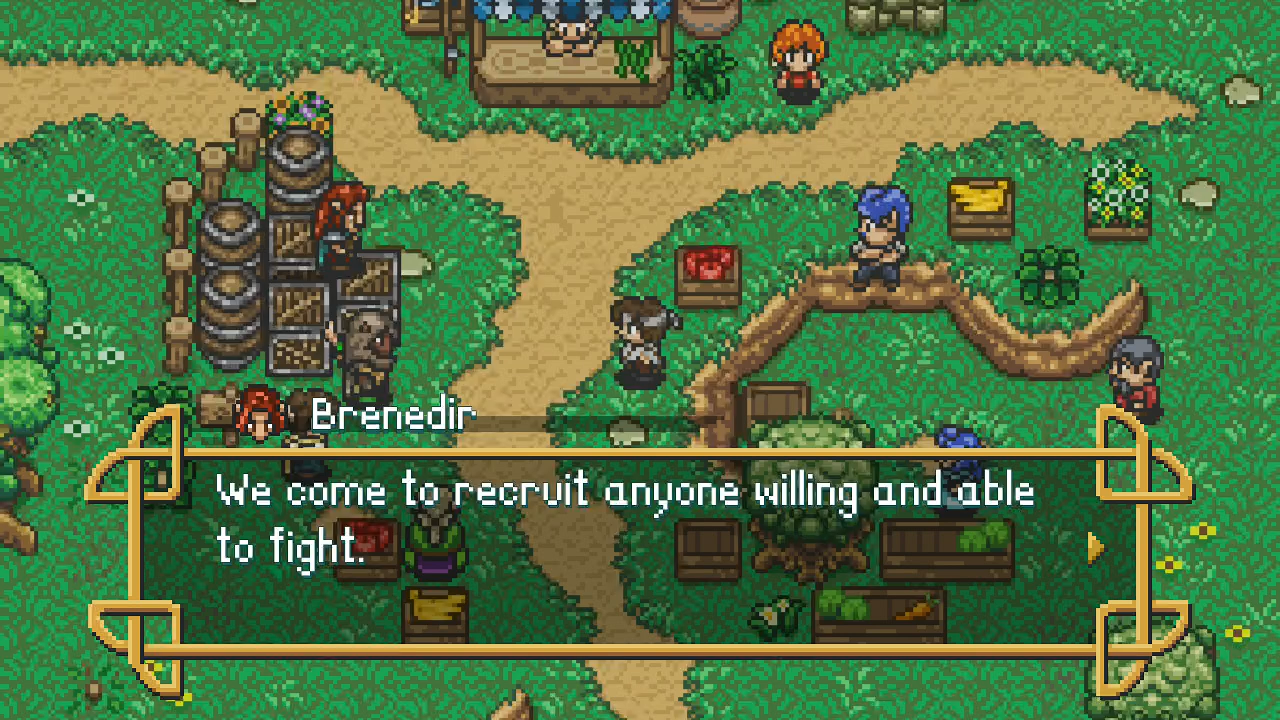

It’s impossible for me to look at a single image from Airoheart and not see how it evokes A Link to the Past. It’s not a one-to-one copy, but the way spaces are shaped and structured is unmistakable. The overworld is typified by green fields dotted with brown cliff faces, light green stones, and tree thickets. Caves and temples lead to the underworld where the land’s monsters and evildoers lurk in labyrinths protected by innumerable sealed and locked doors. Friendly non-player characters in Llanfair, the Elmer town, are pulled directly from Kakariko Village, with bulbous exaggerated heads and enormous hairdos styled in unlikely colors. In the difference between copying something with tracing paper and copying it from memory, it falls firmly in the latter philosophy.

The similarities are more than just graphical. Airoheart’s journey begins when he is awakened in the home of his elderly guardian by a disembodied voice. Caves and dungeons are often swamped by darkness, forcing Airoheart to grope through the darkness for light sources or doorways. The hero’s path forward is often impeded by deep water, but I can find ways through lakes and rivers by guiding him through shallow paths marked by more lightly-colored water.

These evocative features seem to be more deliberately chosen, as they often subvert expectations set by A Link to the Past. The disembodied voice is obviously sinister, a light source as reliable as Link’s lantern never presents itself, and Airoheart never discovers a way to swim through deep water.

It’s these inspirations from A Link to the Past which contributes to the many places where Airoheart struggles to be engaging and fun. I feel this most significantly in its presentation. Almost every environment and the characters within them are rendered in deep shades of green and brown that commingle into a kind of graphical mud.

This color palette has the consequence of making important details difficult to make out. My eyes are never drawn to important objects because almost everything blends together, including the player character. On multiple occasions while retracing Airoheart’s steps through spaces I thought we had thoroughly explored, we stumble upon a new object I missed earlier, not due to a lack of tools or information, but because it was lost in the visual mud.

I am confronted with this visual problem right from Airoheart’s first task. He is tasked by his grandfather with visiting the nearby village of Llanfair to buy a fish for their dinner. The fish lies on a vendor’s stall near the center of the village with a golden exclamation mark above it. The exclamation mark is so small and its shade of gold so muted that it is lost amidst the smear of earth tones that make up most of the world. I am embarrassed by the number of times I walk by before I finally spot it.

My problems with the mud-like color palette are compounded in caves and dungeons by the lighting system. While the overworld is clearly lit by the daylight sun through most of the adventure, subterranean areas rely on local light sources to guide Airoheart’s journey. The further a space is from a light source, the more it will be bathed in darkness.

This lighting system is an impressive technological feat by itself, but as implemented here it exacerbates the existing color palette problems. Underworld areas substitute green and brown for shades of grey, then add onto it an omnipresent and growing darkness. Darkness is a prominent theme, consuming more and more of the adventure as it nears the conclusion, until the final dungeon which is explored in near-total darkness with hardly a tool available to spark some light.

The oppressive murkiness of dungeons can often make something as simple as walking across the floor a deadly challenge. Several dungeons feature trapped floors which activate arrow traps concealed in the walls when Airoheart trods upon them. These trapped floor panels are visually distinct from their neighbors, but the effect is so subtle and is so easily lost in the omnipresent darkness that I often turn the hapless player character into a pin cushion trying to walk across a room.

Even when I am having some success at reading Airoheart visually, playing it remains a struggle because of how it feels. The way enemies react to the player character is a particular problem. They bounce back when struck by Airoheart’s sword, just like in A Link to the Past. But they don’t bounce back far enough, often continuing their attacking animation straight into Airoheart’s body. He dies more times early in the adventure than later because his three starting hearts are easily shredded by the most basic enemies as they blunder forward, heedless of the hero’s efforts to defend himself.

Simple survival is made even more difficult by how stingy the world can be at providing resources. Early on, I direct Airoheart to slash every bush in the desperate hope that one will contain a healing heart. I eventually stop, since none of the bushes seem to contain hearts, but many of them do contain angry bees which deal yet more damage and are difficult to dispatch with Airoheart’s sword.

A lack of resources is also a problem in dungeons. One boss seems to be vulnerable only to bolts fired directly into its eyes from a crossbow. The crossbow is difficult enough to aim reliably when not under pressure from an attacking boss. The number of bolts Airoheart can carry is limited and the arena offers few refills, potentially creating a scenario where the boss is impervious to the only remaining tools and simply cannot be defeated. I am forced to get poor Airoheart killed so we may try again with renewed resources.

Having to reset a boss fight like this is frustrating. It’s not the boss that kills Airoheart, it’s the tiny targets with nebulous hit boxes and the videogame’s own refusal to replenish vital resources which does the job. I also encounter at least one situation where Airoheart becomes trapped in a dungeon section with no way forward or back. I resort to killing Airoheart on an arrow trap to return him to the dungeon entrance to find a different route, though I admit I may have simply missed a vital switch that is lost in the mud and darkness.

When I’m not grappling with annoyingly persistent monsters and stingy resources, I am grappling with how the world is constructed. The overworld is a labyrinth constructed from natural objects, with rocks, trees, and cliffs forming natural barriers that must be explored and maneuvered around to progress. Some gaps between these objects lead to valuable treasures or new locations. Other gaps cannot be moved through at all, even though they appear wide enough for Airoheart to slip through. I spend a good amount of our time exploring the overworld guiding the player character into gaps only to find they are covered by invisible walls. To be surrounded by dozens of potential paths forward of which only a few can actually be traversed becomes quickly discouraging.

I am frustrated to write these many words since I can recognize an ambitious and imaginative videogame beneath Airoheart’s fundamental failures.

While the darkness makes the dungeons difficult to navigate, there’s no denying that it creates an impressive and daunting atmosphere. Darkness’ increasing presence during the adventure represents the ultimate villain’s growing power and influence within the world. If everything else wasn’t so difficult to read and interact with, I might even be complimenting Airoheart’s use of light and darkness.

I like how fast travel is handled. While exploring the world, Airoheart discovers paintings of the world that materialize in the air. Touching these paintings sends him to a magical palace where the world map is inscribed on the floor. When Airoheart discovers a new painting, it is added to this map, and he may return there by running across its mark on the floor then exiting through another portal. It’s an overly complicated system to quickly return to areas we’ve already been, but it’s conceived with so much imagination I can’t help but admire it anyway.

Airoheart’s journey is meticulously chronicled in his personal journal. Every step on his main quest is written down there, as well as any sidequests he comes across. These sidequests are accompanied by a picture of the character who starts it, and when we have finished that sidequest a checkmark is placed on the character’s portrait. As with the fast travel system, it’s an extra complicated way of representing a quest menu, but it’s done with such extra effort that I smile at its exertions.

Where I most feel Airoheart’s ambition is its story. This is where it steps away from A Link to the Past the most, building a plot around refugees in a hostile land and children caught between conflicting heritages. Yet even here, the good I want to trumpet is let down by execution. Airoheart’s outcast brother is spoken about instead of participating through most of the story, denying me many opportunities to witness their contrasting experiences of living in Elmer lands with Breton heritage. For a more minor complaint impacting the story, the script is riddled with sentence fragments and misplaced punctuation.

I try to avoid making direct comparisons to other videogames in my reviews, but I feel here I must make an exception. Airoheart fails largely because it wants to be A Link to the Past, but it does not have a strong enough grasp of how its inspiration worked to recreate its success. Its color palette makes it difficult to understand the world without spending inordinate time squinting at its fine details. Innumerable tiny factors of how it feels to play collide with each other to create a sense of obnoxious and frustrating difficulty. I like a few of its original ideas on their own, but when added into the overall package they do nothing to inspire my good feelings which are stamped down by fundamental failings. Airoheart is too inexpertly crafted to be enjoyable.