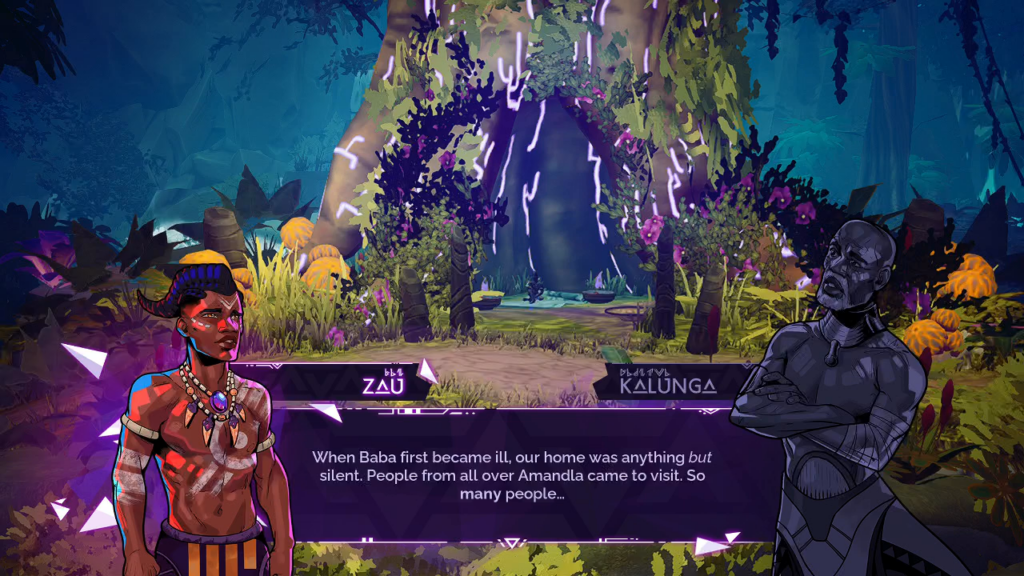

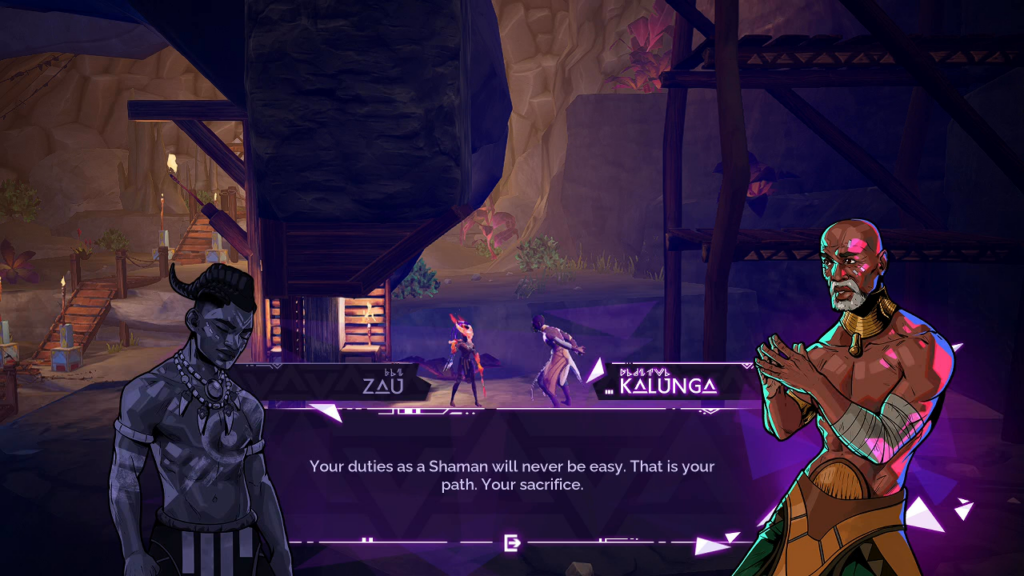

Tales of Kenzera: ZAU is a non-linear platformer about two young African men learning how to grieve the recent passing of their fathers. It begins in a framing device focusing on Zuberi, the son of a writer, who lives in an Afrofuturist metropolis named Amani. Zuberi’s father left his son a book with instructions that it should be read after his death. This book is the videogame’s real story. It follows Zau, a young man who feels inadequate to replace his recently deceased father as the Amandla tribe’s shaman. Zau makes a deal with the death god Kalunga: If he can deliver three Great Spirits who have refused to pass into the realm of the dead, then Kalunga must return his father to life. Kalunga agrees to the bargain and Zau’s quest across the land of Kenzera begins.

Tales of Kenzera is strongest in its combat. Zau’s deal with Kalunga has unsettled the spirits of Kenzera, who attack him in waves at chokepoints across the map. To deal with these threats, Zau is equipped with two masks, the Mask of the Sun and the Mask of the Moon, which I may toggle between at any time with a button press. The mask Zau wears determines his moveset. While wearing the Mask of the Sun, he wields two short spears in each hand to stab at hostile spirits. While wearing the Mask of the Moon, his attacks become ranged, firing bursts of energy from his arms which I can point in any direction using the joystick.

These systems do a great job ensuring I spend at least some time using both Masks. Some enemies can fly or are adept at dodging melee attacks, so it’s not only prudent to use the Mask of the Moon against them, it’s often necessary. Other enemies are so aggressive that trying to keep them at range is difficult or outright pointless, and so emphasize using the Mask of the Sun. Strategically switching between Masks in response to the changing combat scenarios is explicitly described as a Dance by the tutorials.

Despite these tradeoffs, I do find myself favoring the Mask of the Sun in ways that do not feel totally preferential. The Mask of the Moon is limited by a cooldown mechanic. It can fire a small number of projectiles in succession then must stop for a second before it may fire more. The Mask of the Sun encourages pressure from constant, aggressive attacks that is nearly always more efficient and powerful at dispatching spirits.

My favor exacerbates as Zau accumulates Ulogi, experience points earned from defeating spirits and discovered in small caches placed in Kenzera’s out-of-the-way corners. Spending Ulogi to upgrade the Masks further specializes them into their niches. The Mask of the Sun adds new steps to its attack combo and eventually lights enemies on fire, encouraging even more aggressive play. The Mask of the Moon adds an active reload mechanic. If I press a button at a precise moment during the cooldown period then the Mask can fire its projectiles sooner and with increased power. The reticle that marks the active reload period is tiny and appears above Zau’s avatar instead of on the interface, often becoming lost in the frenzy of combat. As a result, much of my time when Zau wears the Mask of the Moon feels like waiting for his projectile attack to refresh punctuated by pinpricks of frustration as I once again fail to hit the active reload target.

When the Mask of the Sun is easier to use and gives greater results, I feel little reason to use the Mask of the Moon except when Zau’s present situation demands it. This is still fairly often, so the Mask of the Moon is never forgotten, but it also never feels like the equal Tales of Kenzera would have me believe.

The other significant complicating factor brought to the combat is spirit. Spirit accumulates in a segmented meter beneath Zau’s health bar whenever he damages an enemy. When one meter segment is filled, he may use it to restore a lost portion of his life bar.

If two segments of the spirit bar are filled, Zau may use them to perform a powerful Spirit Attack. This ability changes form depending on the Mask he wears. The Mask of the Sun creates a fiery whirlwind called Supernova. The Mask of the Moon fires a beam of concentrated energy across the screen called Lunar Blast. Here, at least, is where the Mask of the Moon feels more useful than the Mask of the Sun; Lunar Blast doesn’t feel any weaker than Supernova and has the additional perk of being aimable. I use both abilities many times. I use Lunar Blast far more.

These competing uses for the spirit meter create an interesting tradeoff. Spirit Attacks are especially useful against bosses and more powerful enemies but using them sacrifices two opportunities for Zau to heal. Sometimes that’s a bad tradeoff. This prompts me to constantly evaluate the present combat situation and decide if the gamble is worth the potential results.

Tales of Kenzera only has four bosses but they are admirably diverse in their designs. One traps Zau in a labyrinth of tangled vines and earth instead of a traditional fight against a giant monster. To win, Zau must search the labyrinth for the boss’ weak points while running from a black mist that kills him on contact. Another boss fight begins traditionally enough, but then concludes with a race through volcano tunnels away from surging lava that requires expert use of every skill Zau has learned. Even more conventional encounters, like a giant bird fought on a mountaintop, will introduce complications like a lightning storm that are just as dangerous to the protagonist as the monster. Every situation gains a new layer of drama when I remember that the Great Spirits are not totally malicious. Each of them struggles against a fate in Kalunga’s realm of the dead.

As a non-linear platformer, Tales of Kenzera is much less interesting than its combat. It makes the bold choice to have Zau begin his adventure with a double jump and air dash already in his repertoire, clearing the design field for more interesting movement abilities to be introduced sooner. A magic stone has the power to freeze water, letting Zau run up an otherwise impassable rushing river or use a pounding waterfall as a foothold for wall jumps. Later, he finds a spear that powers a switch, tasking Zau with racing through intricate obstacle courses against an energy spark which temporarily opens a doorway forward.

These obstacles are interesting and engaging on their own, but they are scattered across a simple map. Zau’s journey begins in Patakatifu, a magic circle where he first contacts Kalunga. The three Great Spirits he must pacify are found at the ends of three paths which branch from this central point. On each branch, Zau follows a straightforward path until he encounters an obstacle he needs a new ability to pass. Later, he finds a door which requires multiple nearby keys to open. At a dead end beyond this locked door he has a climactic encounter with a Great Spirit. This pattern is recycled dutifully and predictably across all three branches. By the time Zau enters the third and final branch the predictability of the ensuing events saps much of the mystery from the exploration.

Kenzera is as predictable on a micro level as it is on a macro one. There is one central, linear path leading to the end of each branch. Any routes that break off from this path soon loop back around themselves. This looping design has tradeoffs. It creates a streamlined and focused videogame as Zau is constantly directed by the shape of the world towards his goals. It also creates many long, empty corridors where he runs for great periods without encountering hostile spirits or notable platforming obstacles. This sensation is exacerbated by a lack of fast travel points, just one per region, which can make backtracking to a previous area unappealing.

The greatest downside to the looping level design is it saps the spirit of exploration from non-linear platforming. It’s not difficult finding Kenzera’s collectables and upgrading Zau to his maximum potential when a glance at the map makes it obvious where all its secrets are “hidden.” A small, circular area denotes a platforming challenge course that rewards an equippable, combat-enhancing Trinket. A Baobob tree marks a grove where Zau can reflect on memories of his father to extend his life meter. Temples contain Spirit Rituals where Zau may compete in combat challenges for upgrades to his Trinket slots and Spirit Meter. None of these are hidden. They’re clearly visible on the map Zau receives as soon as he enters a region, waiting for him to come and claim them.

I’m not certain that Tales of Kenzera’s looping level design and unmysterious secrets are really a problem. Though non-linear platforming purists may be disappointed in how Zau is always kept pointed towards his goals, I never feel like he has been plucked from where I want him to be and moved to a place the narrative wants him to be. The level design is built around keeping the player character’s attention centered on the narrative and not on pursuing enhancement tokens and it performs that task well.

Where Tales of Kenzera struggles as a non-linear platformer is in a more fundamental area: The act of platforming itself is not as precise as the often intricate obstacles demand. The instant-kill spikes which litter the walls of many areas are a particular problem. Their hit boxes seem much larger than the actual spike’s forms, causing the exhilarating near-misses that typify platforming to instead end with Zau unfairly dying. Luckily, checkpoints are placed seemingly every few feet so a brush with death rarely sets Zau too far back. After a cry of pain, he appears in a flash almost exactly where he died, ready to try surpassing the troublesome obstacle again.

When I become frustrated by Tales of Kenzera’s often imprecise platforming obstacles, I am sustained by the interplay between its main characters. Kalunga in particular is interesting. Despite his occupation as a deity of the dead, he is not a sinister figure. Instead, he acts as Zau’s companion on every step of his quest, never directly interfering but often voicing his opinion. The advice he offers fluctuates over the story’s course. The god chides and criticizes Zau early on for his zeal and eagerness. Their bond deepens as the Great Spirits are pacified and Kalunga becomes more empathetic and encouraging.

In another videogame, perhaps one based on more broadly European concepts of grief, death, and gods who embody those ideas, Kalunga would be a grim and adversarial force. In Tales of Kenzera, I never feel that Zau’s bargain with Kalunga is anything but genuine and fair. Their relationship is warm and supportive as ideally befits an elder mentoring a pupil.

The other major relationship is between Zuberi and Zau. Though the two never meet, their contrasts depict the central theme of Tales of Kenzera.

From a distance, Zuberi and Zau appear quite different. Zuberi resides in an Afrofuturist city called Amani and seems to live in apparent wealth and privilege. All I ever see of Amani is a beautiful vista from Zuberi’s apartment balcony, so I cannot assume much about the city. My hope is every person there lives in the kind of opulence and comfort Zuberi and his Mama enjoy. Zau seems to exist in a less advanced world, or at least one where the technological bounty Zuberi enjoys is hidden or restricted. I cannot make the assumptions about Kenzera that I do about Amani. I see in all three branches of Zau’s journey that its populace struggles with survival. As Zau strives to deliver the Great Spirits to Kalunga’s realm of the dead, the land of plenty seen from Zuberi’s balcony seems worlds away.

The connection the two share is through their deceased fathers. Both inherit their father’s occupation and struggle to succeed in their new roles, Zuberi as a writer and Zau as the Amandla Shaman. As Zau defeats the Great Spirits, he learns a new lesson from each about different kinds of grief—a child for a parent, a parent for a child, and between friends—and that lesson is in turn communicated to Zuberi.

At first this framing device seems unnecessary. While Zau’s plot is pivotal to Zuberi completing his arc, nothing Zuberi does contributes to Zau completing his. If this were a much longer videogame, I would forget Zuberi exists as the framing device is only visited during the story’s introduction and climax. Then Zuberi reaches the end of his father’s writings and finds the story has no ending. It is up to him to use the lessons he learned through Zau to complete the story and ensure both young men can find closure. Zuberi’s Baba is a wise man indeed.

There’s a lot to admire in Tales of Kenzera: ZAU. I am no expert on African culture, but it seems to be an authentic and heartfelt portrayal of the many cultures which thrive there. Zuberi, Zau, and Kalunga are all appealing and relatable characters with understandable, universal conflicts in which I have no difficulty immersing myself. I have more trouble enjoying it as a non-linear platformer. The combat is the standout, though I struggle to see the Mask of the Moon as equal to the Mask of the Sun. The actual platforming is the low point. Kenzera’s obstacle courses are not insurmountable but Zau’s movement through them often feels imprecise, resulting in many deaths that feel outside my control. This is far from a reason to avoid playing Tales of Kenzera: ZAU. It has heart and grit. I hope to some day play another Tale of Kenzera with more refinement.