Neva combines cinematic platforming and puzzle platforming elements to tell the story of a beast named Neva and her relationship with a nameless human player character as they fight for survival against an overwhelming force that corrupts everything it touches. At times they race for their lives across precisely designed platforming environments. At other times they slow to a leisurely stroll to solve simple puzzles and explore small spaces. By the end of a tight four-hour playtime, I have followed the pair over a single fraught year, witnessing a story about the cyclical nature of existence and the small, significant choices individuals can make that disrupt its endless flow.

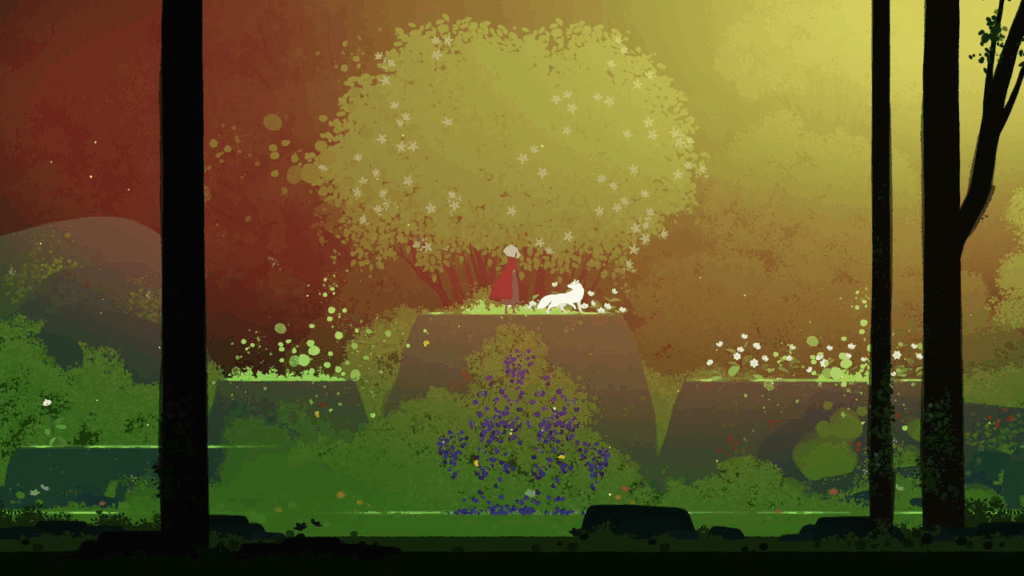

I am never given much firm information about this videogame’s setting. It rejects exposition, preferring to use its small amount of text to give brief gameplay instructions instead of introducing characters or concepts. Neva appears to be a white wolf, but she dwells in a colorful environment and has two horns that resemble tree branches growing from her head. The setting itself is an idyllic and peaceful forest created with sponge painting techniques. The plantlife’s vivid coloring and wild animals with too many horns and tusks suggests this environment is an alien or fantasy world. While unusual to my perspective, these features all fit together. The truly foreign addition to this setting is the human player character. She is a woman with dark skin and a gloriously bouffant afro, wearing a flowing, expressive cape, and wielding a long, slender sword. How she came to this place and her original purpose for being there is never explained or permitted even a brief allusion.

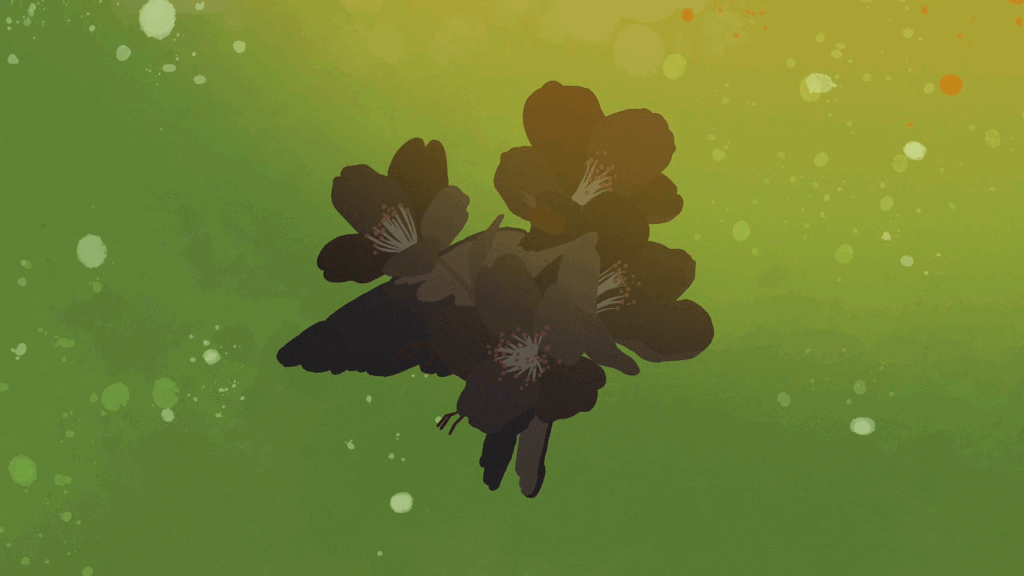

The player character uses her sword to defend herself and Neva against the videogame’s antagonistic force. It appears as a black wave that overwhelms everyone and everything, subjecting its victims to a corrupting, writhing death distinguished by the black flowers that bloom from their bodies. The wave is at once a single mass and a collective force, able to split off parts of itself into vaguely humanoid shapes with expressionless white masks for faces. They make croaking, quavering roars as they lunge at their victims with grasping, limber fingers. It is an army of these creatures that attack Neva’s mother in the story’s first few minutes, killing her and prompting the player character to step up as Neva’s guardian.

The player character’s service as Neva’s guardian takes place over the four seasons of the year. Activities, visuals, and most importantly, how the player character interacts with Neva as she rapidly grows into maturity depends on which season the plot is currently set in. To describe them with any detail is to give away much of what makes them unique. Neva is the kind of videogame that is most interesting, most beautiful, and most affecting when it is played with as little information as possible. If you’re already convinced, stop reading here and go play.

Interacting with Neva is an important activity, so much so a button is dedicated to the action. Pressing it causes the player character to call out Neva’s name, either calling the beast to her side when Neva is on screen or calling out with concern when Neva is not. Standing near Neva and holding the button down commands the player character to stroke her coat. This has different effects at different times. During Summer, this comforts Neva when she is distressed by the corrupters. During Fall, it helps Neva to channel her unexplained powers into a rejuvenating howl, transforming the sickly black flowers created by the corrupters into colorful ones full of life.

Many of Neva’s other capabilities change as she rapidly matures over the four seasons. In the Summer, she is still a pup, relying on the player character to protect her from the corrupters, guide her through the forest to safety, and provide her with emotional support after her mother’s death. By the Fall, she has grown much larger and joins the player character’s sword swings as a spirit to help fend off the corrupters, who have increased their numbers to overwhelming proportions. I dislike this development as it adds a command to hurl Neva at a corrupter or an element in the scenery, transforming this creature the player character helps nurture in the first hour into what is essentially a gun during the second. This idea is thankfully downplayed in Winter when Neva is almost fully grown and the player character is able to ride on her back. This enables spaces to grow much larger and chase sequences against relentless corrupters to become much faster and more elaborate. The relationship between beast and human is inverted by this time when Neva often acts as the player character’s protector.

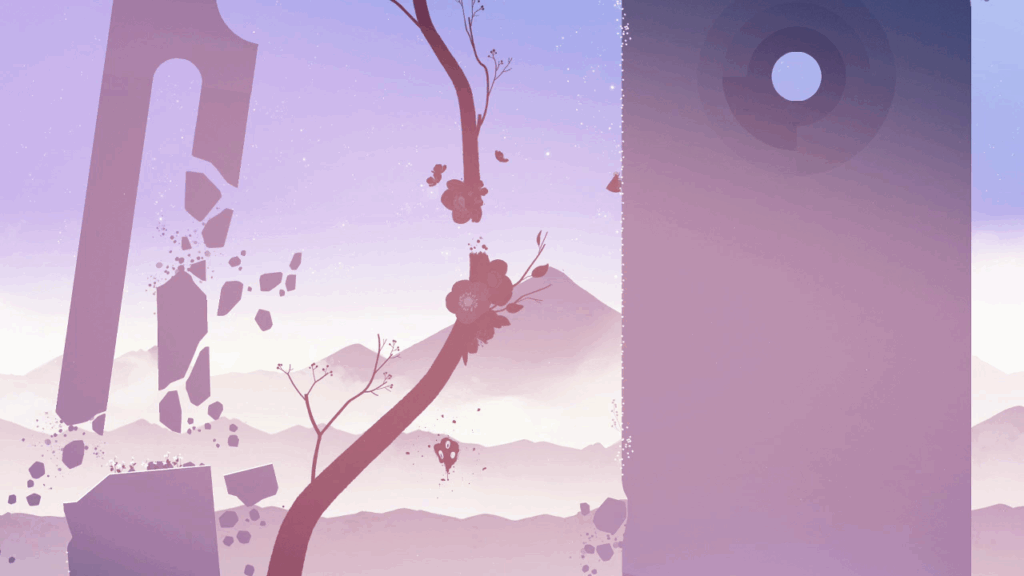

At periodic points during their trek for safety from the corrupters, Neva and the player character are impeded by small environmental puzzles. These are simple speedbumps, not brain busters, requiring no more than to stop for a moment to observe the environment before continuing. Like the player character’s interactions with Neva, they change according to the season. In Spring, the player character must create paths through stationary corrupters that young Neva can follow, or find ways to reunite with the pup when they become separated. In Fall, the puzzles become more about finding ways through the environment as Neva has become more independent and the corrupters’ presence has transformed the land in unsettling ways. By Winter, the world has been almost totally upended by the corrupters, requiring the player character to find paths through the crumbling environment by smashing fragile blocks and navigating curious hallways where platforms are only visible by their reflections in eerie pools of water.

The periodic puzzle spaces are punctuated by frequent combat with the corrupters when they take their more individualized forms to attack the protagonists. The player character’s combat abilities are basic. Buttons prompt her to swing her sword, to roll forward, and to jump. Corrupter attack patterns are almost as simple. Nearly every single opponent can be defeated by rolling forward through their attack, then turning to attack their backside until they retreat or succumb. The exception are the corrupters that sprout wings and attack from the air. They require more care as their attacks are more difficult to read and jumping up within a sword’s reach leaves the player character vulnerable.

The combat’s easy difficulty makes its existence feel like it’s meant to be thematic rather than challenging. It emphasizes the desperation—and later, the sadness and the fury—of the player character’s struggle. She even recovers hit points by striking corrupters, emphasizing an aggressive playstyle. If the player character does die, a generous checkpoint system ensures she’s never more than a few seconds away from where she died. If the combat still feels too difficult, I can toggle Story Mode, which removes the player character’s ability to die entirely.

The periodic boss fights are much more interesting than the standard enemies, requiring a great deal more skill and finesse to overcome. Their designs are as varied as the seasons. A brute of a corrupter makes sharp roots burst from the ground when the player character draws close and swings at her from a distance with an elongating arm when she stands afar, forcing her to weave back and forth across the battlefield to stay alive. A nimble, quadrupedal corrupter requires precisely timed jumps to avoid its many attacks, then is joined by a partner to make the fight even more hectic just when I think I’ve got it figured out. A late fight against a giant corrupter inexplicably wielding a katana replicates the standard roll-then-attack-it-from-behind strategy, but makes up for the repetition with sheer speed and aggression, demanding all my skill and concentration to overcome. Collectively, they offer a satisfying balance between challenge and novelty that is far more engaging than the simple standard enemies.

This videogame’s play elements are adequate. They come together to form a series of activities that keep me engaged across its short runtime. They are not what makes it good. The reason to play this videogame is its visual design. The way it uses colors and shapes to portray this world being undone by the invading corrupters is haunting, at times beautiful, at times horrifying, and always made with top-notch artistic talent.

I am introduced to the corrupting force right away. Even before Neva or the player character appear, I see a bird in flight, a quaint and banal image of natural beauty and freedom. This is shattered in an instant when the bird unexpectedly falls dead mid flight. Its body lands in a field of bountiful grass, putrefies in a moment, then sprouts the black flowers that will become a familiar sight in the coming hours. Neva and the player character enter here, investigating the grim sight—which turns to terror when they are pelted with the corpses of dozens more dead birds. This heralds the first wave of the corrupters, who crash across the field, nearly killing Neva and the player character but for the intervention of Neva’s mother, who perishes in the struggle.

The corrupters impact much more in the setting than its animal life. They seem to settle into the ground and plantlife and change the natural functions of the world. I see their influence as it desaturates the world’s vibrant colors beginning in Fall, the natural golds and browns of autumn slowly being consumed by a miasma that overwhelms the scenery by the season’s end. This is accompanied by a crumbling of soil and trees that, instead of collapsing into a heap of fallow earth, rises into the air in defiance of gravity, creating some of the videogame’s most unique platforming sequences. Few of the forest’s animals survive this transformation. Their bodies have become the playthings of the corrupters, who leap down their throats to animate their limbs, attacking Neva and the player character in an especially grisly take on a zombie apocalypse.

By Winter, the corrupter’s infection of the world seems complete. There is no more color, only stark black and harsh white surfaces sporadically lit by an alarming red that seems to have no source. The natural world is gone, replaced by structures made from the corrupters themselves, twisted into a macabre cathedral filled with orderly pillars. Neva’s and the player character’s race for survival feels especially futile in this period; there seems to be nothing they can do to beat back the overwhelming tide of corruption. All they can do is survive. Yet even in this bleak and barren environment, life goes on, and a child’s development into adulthood is inevitable.

Spring is the briefest chapter. It is an epilogue, providing closure to the story and giving me the final clues I need to understand what the videogame is trying to say. It brings with it a welcome explosion of color, a great deal of hope, but also a threat and a warning. Neva and the player character have overcome the corrupters for now but nothing lasts forever.

If I were to evaluate only its platforming features, Neva would be an adequate videogame. Its combat is fast and easy, its puzzle platforming is competent and mindless, and its cinematic platforming is direct and never throws a surprise in the protagonists’ paths. Only the bosses provide even a threat of challenge. A generous checkpointing system and the option to completely remove the penalty of death defangs them. These core gameplay elements are not the reason to play Neva. Its visuals are. Detailed and expressive character designs make the relationship between Neva and her guardian a believable and affecting one. More visually impactful are the corrupters. Their seemingly unstoppable desecration of the idyllic forest and its gentle inhabitants is captured through brilliant use of color and atmosphere. Despite the millions of dollars put into big budget horror videogames to create rotting corpses and grotesque visages, this is one of the scariest videogames I’ve played in recent memory. Neva’s basic platforming design keeps me playing, but its visuals keep me fascinated.